“Dunhuang is the place we long to go back to.” I wrote that in May 2001, twenty-four years ago. Nearly a quarter century later, I’ve been invited to speak about cross-cultural exchange in literary narratives at a conference there, organized by the China Writers Association.

Why did we long to return to Dunhuang? In part, because we had far too little time there. Our flight from Xi’an was delayed because of a sand storm and we had spent the previous night in a hotel with thin bedding and no hot water for tea. I described it as “spooky and smoky.” We’d turned away from the restaurant, which had dead fish floating in its tank, and eaten trail mix for supper. And our next stop in Urumqi and Kazahkstan were fraught with disappointment—Urumqi because the museum we’d come to see was closed for the year and Kazahkstan because, well, nearly everything. (I’m the one who insisted we go there.)

We have no photos from Dunhuang because my good camera had stopped working in Xi’an and we weren’t able to buy a substitute until we got to Almaty. My notes about Dunhuang remind me that, “The hotel looked like a desert fortress, with thick stone walls and carpets spread across the slate floor in the cavernous reception area. The rooms were done in the same indigenous style, reminiscent of the American southwest, with solid wood furniture, richly colored rugs, and high ceilings. I hadn’t realized that the decor of our hotels had depressed me—and we hadn’t yet got to Kazakhstan, where the Soviet decor was only the beginning.”

Fifteen-year-old Tom did a better job of describing our brief visit:

Day 8: I love Dunhuangl We are staying in the Silk Road Hotel, which is apt as Dunhuang used to be a major hub for the silk trade. We were quite surprised at its appearance. because it looked like a castle in the middle of the desert, II also had been patronized by the Bill Gates, which was really cool. Oh well, I guess if it's good enough for Bill Gates, it's good enough for us.

What was really great about today was when we went to visit these huge sand dunes down the road. Each one is larger than Monument Mountain, and Rachel was raring to climb up all the way. We climbed a little way up and looked at the camel being offered as rides. They are really big! These sand dunes are really the coolest things I have seen so far. I wish we were here longer so that we could climb the sand ridges up to the top. Halved wooden boxes were being rented to go down the mountain. They weren't tapered at the front, so all that you could do to go down was go a few meters and push with your hands.

A pleasant surprise was the restaurant at the hotel. First mutton I've ever tasted. The help, young girls perhaps my age or a year or two older, were so kind that Rachel and I brought them some brightly colored sugar Easter eggs. the hollow ones with bunnies and birds inside. It didn't look like they had anything like that in Dunhuang, so I figure they'll keep them for a while.

Day 9. Oh my god! There's so much to see at these Buddhist caves! I was never aware of how much the Buddhists in this area would put into caves, or how many there would be. From my estimates, there were at least two hundred caves. each the size of a really high and wide living room. They were built over a period of five hundred years by Buddhist monks who had settled there after their leader had seen the image of the Buddha rising over the hills across the valley.

The monk had two monasteries and an extensive collection of old manuscripts and artwork. These mysteriously disappeared when the last cave was finished--until 1900, when the last monk of this order found a secret cave in one of the older caves, whose entrance had been sealed off. Inside there were millions of scrolls and paintings in almost perfect condition. This has become known as the secret library of the Mogao caves.

One of the most sickening part of the history of the caves is the story of certain American archaeologists who came in the 1920s and, using weird chemicals, stripped portions of the beautiful murals away, imprinting them onto canvas, and hauling them away to the USA. This was done by many countries, and all of Mogao's statues, ornaments, and gold-leaf decorations have been stolen, including most of the contents of the secret library.

China has tried to regain many of these items, but unfortunately we're stubborn about parting with our stolen merchandise. Makes me quite ashamed.

Finally, we arrived at the last three caves, each of which held a massive Buddha. The first was around seventy feet tall, or four stories, all inside a cave. The second held yet another Buddha, maybe slightly bigger, with a few broken fingers. The last cave held a massive sleeping Buddha, longer than the others were tall.

lt's so dark you can't make out the stunning frescoes and mural without a flashlight, but when you do, the colors are so brilliant you could swear they were actually coming out of the flashlight beam.

When the children found the first of the huge Buddhas, they ran to find me and made me close my eyes and let them lead me, blind on the rough steps, into the cave. Tom shone the flashlight, “Now open your eyes, Mom!”

Tom’s account of the Mogao caves is fairly accurate. It comes from the report he was required to write for a class, to prove that the trip had been educational. You can read the short article about the caves by Professor Jian-Zhong Lin, which we later published in the Encyclopedia of Modern Asia (the project that inspired our 2001 trip), by clicking here.

He closed with this:

The airport here is the size of a large McDonalds, with only one small departure lounge. We had to simply give the people there our tickets, and go where they motioned. For all we knew we could have been headed to Mongolia. Luckily we weren't.

l will always remember Dunhuang as the most relaxing and beautiful part of my trip, with such cheerful people, great food, and such stunning vistas. I get the feeling l will want to return here soon.

As I look at a map now, preparing for another trip to Dunhuang with a lot more knowledge than I had in those distant days, I note that Gansu Province is shaped like a gerrymandered congressional district: a long narrow territory between much larger provinces.

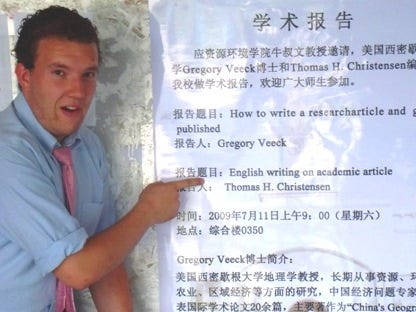

No doubt there is some geological explanation, but what the map makes clear is why Tom never went to Dunhuang even though he spent a summer working in Gansu with geographer Greg Veeck: their base was Lanzhou, at the opposite end of the province.

When I read the news these days one thing that comes to mind is that we need more than ever to learn about China. A bit of dark humor from the New York Times yesterday: “In China, one of many nicknames for President Trump is Chuan Jianguo. It literally translates as “Trump the Nation Builder.” My best translation is ‘Comrade Trump.’ The joke is that Mr. Trump is a patriotic son of China who is diligently advancing Chinese interests by causing chaos in the United States."

I’ve also been invited to visit Shanghai to explore its urban development and third places. In my 2001 notes about Dunhuang, I find this: “The hotel has a study center for scholars so maybe we’ll go back there to write some day.” That day is on the horizon, at the end of May, and you’ll be hearing more about China in future newsletters.