A tunnel under Long Island Sound?

A conversation with Robert Yaro of North Atlantic Rail and some related rail ideas

Even Tajikistan is building high-speed rail lines. Why not the USA? While I’ve been on sabbatical from the Train Campaign, I can’t seem to stop talking about trains and I was especially pleased to catch up with Bob Yaro, who’s been a leader in urban planning for many years. Our conversation at Train Time is linked here (there’s also a transcript), followed by some other news - including the 60th anniversary of Japan’s bullet trains.

Train Time podcast: A tunnel under Long Island Sound?

Robert Yaro, cofounder of North Atlantic Rail, a project he started after retiring from the Regional Plan Association. Bob is especially well known for his work on urban development, but I was please…

The Japanese bullet train has just celebrated its 60th birthday. Sixty years ago Japan had high-speed trains that were - and are - clean, elegant, and comfortable. You can read about them in this gift link from the Financial Times. When I took one from Tokyo to Kyoto in 2001, my first time on such a train, I was what struck me most was seeing a crew moved into the carriage as we were disembarking, to wipe down every seat arm and door frame.

Comparing the US with Europe

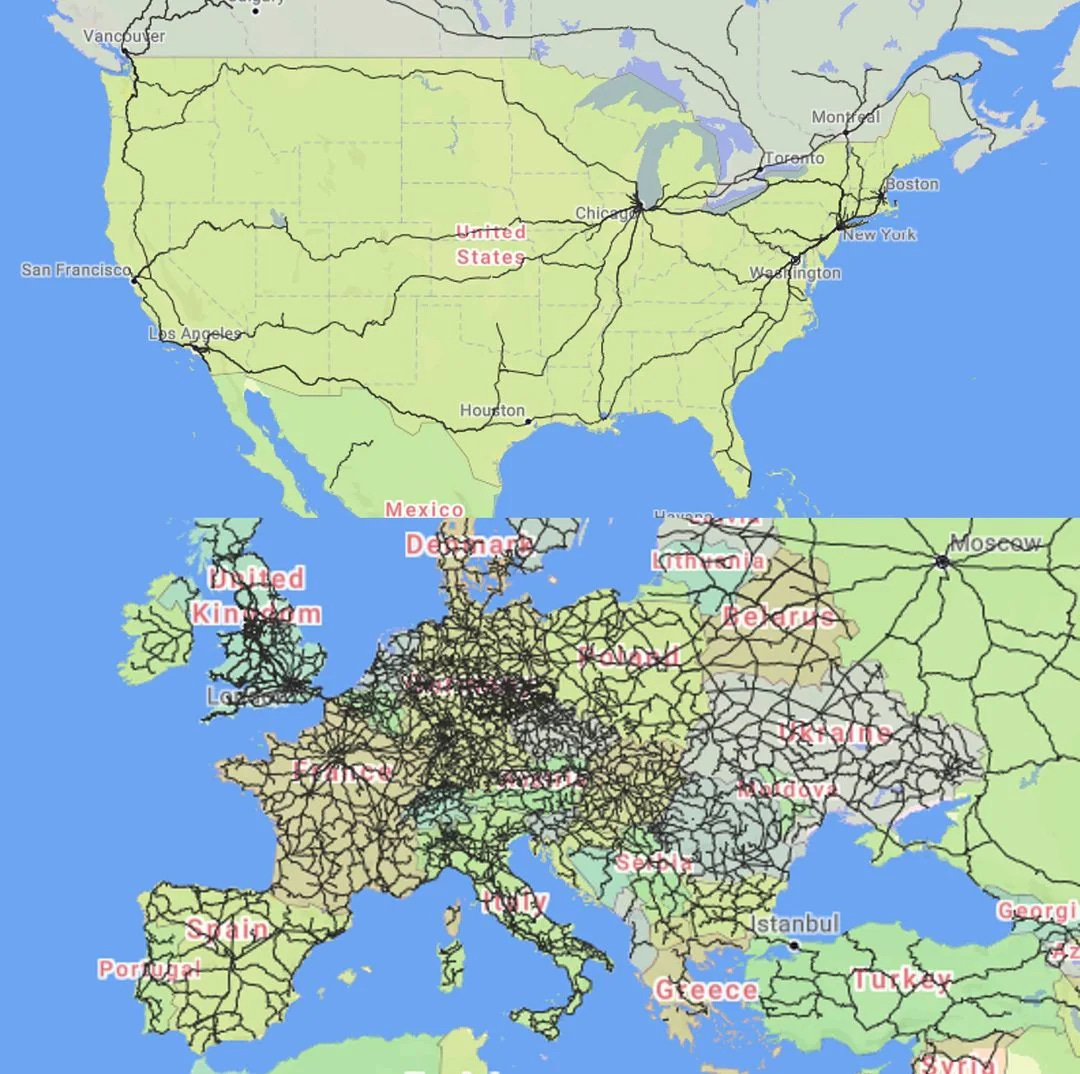

The EU/US map you’ll see below has been widely circulated online. It’s striking, of course, and the general idea is accurate: Europe has far more passenger trains than North America. But the US map here shows only Amtrak lines, not the commuter networks around Boston and New York. Snopes, the fact-checking website, explains this here.

What Snopes doesn’t mention is that there is a network of rail lines used only for freight today, including the Housatonic Berkshire Line. These rail lines once ran passenger trains as well, and restoring passenger service on these existing lines has many advantages. For one thing, they go between city and town centers, where people want to be. Many of the old stations in towns along the routes are still standing - used as restaurants, shops, offices, and homes.

Big or small, fast or slow?

Big projects are necessary and, as Bob Yaro explains, there is no reason the US shouldn’t be able to keep up with Tajikistan. I worry, though, that the biggest roadblocks to passenger rail development in general are being side-stepped by the High Speed Rail projects.

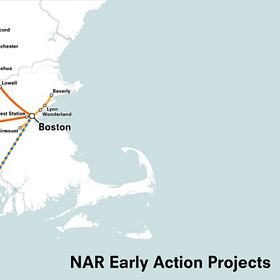

The high speed rail Bob describes in the podcast looks, in my mind’s eye, like short bits of spaghetti thrown at a map. (This infographic at Forbes.com gives a better, or more realistic, picture than the one above.)

On the other hand, it’s important to show that any project should be visualized as part of a network, each strand amplifying the potential of those it touches. As Bob Yaro reminds us, a single airport isn’t much use. And as train and bus lines were cut, and service reduced, of course we were forced to rely on automobiles. One of the things environmentalists talk about is reducing our dependence on private cars, and that is the right way to describe it.

My concern about high-speed rail is that it so often strikes people as a vast tax-payer funded boondoggle, or luxury projects for the wealthy. Most Americans have never traveled by train, and I think it’s important to give people across the country a chance to experience train travel. Before we started building the interstate highway system, Americans had had decades to get used to driving, and could imagine the improvements politicians were promoting.

There is no reason to start only with mammoth projects that will take many years. In fact, it makes sense to fund nimble efforts, offering return on investment within years not decades. The Housatonic or Berkshire Line (which is, indeed, included on the map of the proposed North Atlantic Rail system) is one of them.

But two roadblocks are unique to the US. First, our federal system does not encourage or incentivize states to plan and work together. I live at the corner of Massachusetts with both Connecticut and New York State only 10 miles away, but there is no easy way to coordinate across those state lines. The state politicians we need to support projects in Boston and Hartford and Albany do not know one another - there is no forum in which they ever meet.

Second, our legal system gives priority to commercial freight rail, instead of ensuring that the thousands of miles of existing track, often owned and maintained by the government, are used for passenger service as well as for freight. Shared use is rational and efficient, but requires thoughtful design and leadership - which seem all too often absent from anything to do with rail.

"It's almost as if it went into suspended animation," said Peter E. Lynch, referring to passenger service on the Housatonic Railroad line that snakes near the path of the river of the same name through Litchfield County. "The tracks are all there. The stations are all there. It looks like it was just sitting there waiting to be put back."

An additional roadblock, which is not unique to the US but seems to be a greater problem here than anywhere else on the planet, is excessive permitting. I’m in favor of environmental protection, of course, but also see how regulations can delay and discourage important work. They also increase expense, sometimes making it impossible to create a realistic budget.

Of course the Chinese government doesn’t face these obstacles in building out the country’s rail system. While I hope we can start building our own train cars here in the US, we can learn a lot from other countries: Japan, China, the EU, and even Tajikistan. Here’s a short video my son made in Beijing, showing the pick-up as the train leaves the station. How long will it be when we see a scene like this in Washington DC?

Trains and third places

Two train friends came to supper last week and the conversation turned to third places. It’s easy enough to see the connection between trains, and public transit in general, and the walkable communities in which third places thrive. But there is another point about high-speed rail we need to remember: high-speed trains have to be built on new lines and will rarely, in the US, be able to start or terminate in a city center. Walkability is not part of the equation.

This came up when consultants were offering options for an east-west line in Massachusetts. The existing Amtrak and freight line goes through the state’s three major cities - Boston, Worcester, and Springfield - and on to Pittsfield in the Berkshires and then to Albany, the capitol of New York State. Improving service on that existing slower-speed line would land passengers in the city centers.

But there is also a push for high-speed rail, at a cost of billions. The HSR stations would be somewhere to the north of Springfield, along the line where the interstate runs. Would this help Springfield, the third largest city in Massachusetts with a 32% poverty rate? Every commuters would have to drive to the station. It’s even more of a problem in Los Angeles: the HSR project from LA-Las Vegas will require people to drive to Rancho Cucamonga, a city 37 miles from downtown LA. Las Vegas is another 230 miles away, but probably with far less traffic on the roads.

I think of Wassaic, New York, the sleepy upstate village where Lewis and Sophia Mumford lived for many years. Metro-North restored the rail line from New York to a station 3 miles south of the village. I use Wassaic station and like most people I drive straight through the village (unless I stop to take a look at the Mumfords’ house). This is the opposite of the transit-oriented development (TOD) that today’s urban planners talk about.

I worry that high-speed train systems might distract us from the practical and possible things that could be done swiftly.

On the other hand, I really love the idea of the tunnel under the Long Island Sound! It just seems so 21st-century and globally competitive, instead of having the US stuck with train carriages from the 1970s and train travel often slower than it was a hundred years ago.