We should be feeling better, right?

Days in the northern hemisphere are getting longer. US democracy was not overthrown. The Capitol is intact (though 5 people died and injuries to the police who protected legislators are shockingly high). People are being vaccinated, and taking better precautions, too, it seems.

My daughter says there’s copious evidence that I am stir-crazy: I’ve been talking about growing cannabis, and I just ordered a set of kites. (I haven’t flown a kite since I was 10.)

I lie awake at night, trying to make sense of the world we live in. It feels as though everything will be different when the pandemic is over. Will life be different, or will we forget?

My dear friend Bill (William H.) McNeill was the first historian to look at disease as a major influence on human affairs. His Plagues and Peoples has been mentioned a lot over the past year. (Click here to get his 9-page essay on plagues and peoples from our Encyclopedia of World History.)

Bill writes that after a while people forgot the 1918 flu epidemic, in spite of the incredible numbers of people who died.

Just how many? The CDC says that some 500 million people, one-third of the world’s population, became infected, and at least 50 million died. The world population then was only 1.5 billion. Today it is 7.8 billion, and there have been 100 million COVID-19 cases, and 2 million deaths. That is, we’ve seen 1/25th the number of deaths in a population more than 5x the size.

How could people forget?

I had not grasped the scale of that epidemic, in part because in Too Near the Flame I’m writing about people who lived through that epidemic and were in fact vulnerable young adults at the time, yet they don’t refer to it at all. T. S. Eliot and his first wife were seemingly always ill with something or other, but I can find nothing in the letters about an epidemic in progress. And how, I wonder, could Sophia Wittenberg and Lewis Mumford, young people in New York at the time, not mention the flu in their many letters? In 1918 Lewis had just left the Navy. Sophia had started a job at The Dial magazine. She went to Washington DC for a protest march - young progressives were angry with the president. She loaned a red blouse to Mother Bloor, a workers’ rights advocate who was addressing a crowd at Madison Square Garden. Yet neither of them says anything about taking precautions, or refers to anyone ill or dying.

Bill McNeill, born in October 1917, nearly lost his parents to the disease. Apparently his parents came down with the flu and thought they were going to die. Alone in Chicago after a move and worried about their two tiny children, they tucked the babies into a basket and left it in the hallway of their apartment building with a note asking the person who found the basket to see that the babies were looked after. Fortunately, the young parents survived, as did Bill and his sister.

Years later, when Bill wrote that “survivors soon almost forgot about their encounter with such a lethal epidemic,” he attributed this to the development of antibiotics and other medical discoveries.

I note, however, that of the 50 million who died, only 675,000 were Americans. How remarkable it is that today such a huge percentage of global deaths have come in the richest country in the world. Does this shape our perception of the pandemic’s importance?

What comes next?

When the US began its first lockdowns last March, there were lots of people asking what the long-term consequences would be. Ray Oldenburg and I did a radio interview where we were asked if people would ever again want to gather in “third places.”

Nearly a year later, we know the answer to that: heck yeah! People flooded into pubs and bars, in fact, too early and without taking the correct precautions. But there’s certainly no doubt that that’s where we want to be, and where we’ll be again.

In those early weeks, a few publishers decided to commission books about the “post-pandemic” world. I’ve been looking at two of them, by authors I admire, to see what I could learn, and perhaps recommend them to you.

Nicholas Christakis, a medical expert at Yale, produced Apollo's Arrow: The Profound and Enduring Impact of Coronavirus on the Way We Live, naturally focused on epidemiology and how a pandemic is going to affect our thinking about public health. The trouble with a 2020 book on that subject is that in January 2021 it has already become out of date. But it’s still a great introduction by someone who has also written about positive social and behavioral contagion in Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks.

More in line with what I was looking for is Fareed Zakaria’s Ten Lessons for a Post-Pandemic World. Zakaria does a good job of situating the pandemic in historical and global context. It seems that he was raising the prospect of pandemics more forcefully than most people after Ebola and SARS.

Because he obviously did the last corrections in July 2020, this book too has already become dated, and a downside of this hasty publishing is that the 246-page book has no index. But it’s still interesting to see how he threads the major issues of today into the evolving tapestry of the pandemic.

Here are the dilemmas Zakaria tackles: the pace of change; the quality of modern governance; rethinking the market economy; the crisis of knowledge; digital life; sociability; inequality; globalization; bipolarity and decoupling; idealism.

Enough already?

I appreciate Zakaria’s gallant, optimistic conclusion that we have a chance now to make things right, that the future has not been written. It reminds me of Bill McNeill’s optimism, which came from looking over the whole of human history. We would talk about climate change or some other pressing issue, and he’d say, “Humans have proved themselves to be remarkably inventive and adaptable.”

Most important, Zakaria acknowledges that a whole lot of different things are at play, instead of focusing on one issue. He writes as a generalist, a public intellectual. It’s awfully easy for specialists to lose the plot when they write about the future. If you have a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.

We all need to start practicing “systems thinking,” something I’ve been reading about as I work on the Encyclopedia of Sustainability. But when I read the political news it seems that a lot of people haven’t yet mastered linear thinking, so moving to systems thinking is going to require new efforts at every level of society.

And we need some real breakthroughs in the academic world. Linearity and specialization are rewarded, not big-picture thinking. Much as educators talk about “critical thinking skills” and “interdisciplinary learning,” I don’t see these things having much effect on discourse, or academic research. If you know of efforts in this area, do leave a comment.

One of my ideas is to use this newsletter to gather recommendations and stories from our global networks and then compile and share the highlights as an occasional supplement. I’ve got a long and varied list of recommended books about China, for example, and we have a database of books and movies about community, and human-computer interaction. Do you have post-pandemic reading to recommend? Please share it.

Zoom life: Organization of American Historians

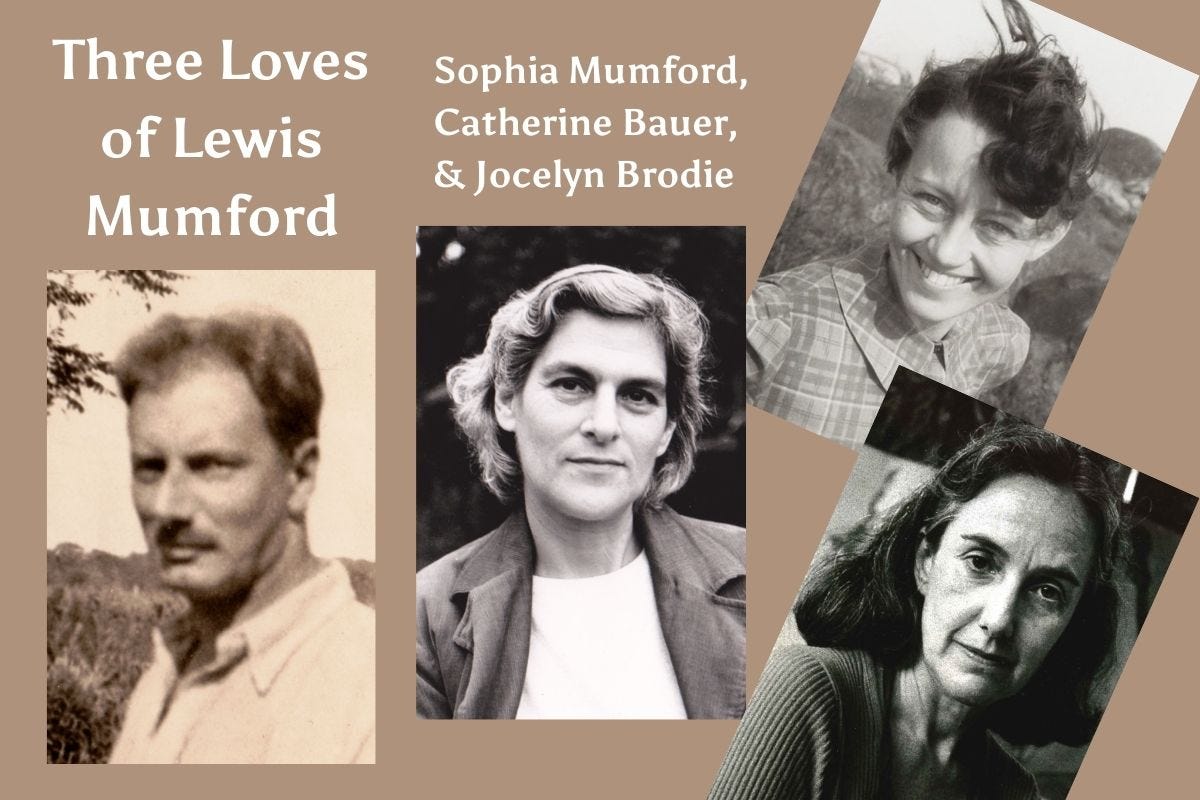

I’ve been working with three colleagues on a panel for Organization of American Historians (OAH) annual conference. It’s not till April, but we have to deliver our recorded session in February, so we’ve already exchanged papers. (No more working on the presentation the night before!) It’s a groundbreaking topic, I think: bringing into the light three women connected with one prominent man, Lewis Mumford. My subject is Sophia Mumford, his wife of 70 years, while two Harvard scholars are talking about for two of his lovers, and we have Aaron Sachs, a historian who is writing a book about Mumford and Herman Melville, as the commentator. Details here.

Tools

Like Lewis Mumford, I think the intellectual life should be balanced with the creative and the practical. Unlike Mumford, I love tech tools. I want to share a favorite or two with you.

Canva.com

The first, Canva, is what I used to create the image (above) for our OAH panel, and the masked Statue of Liberty you might have noticed in my last letter.

I was dubious when I first read about Canva, a graphic design app. I had always employed a full-time graphic designer and when the last one left I was worried.

On the other hand, book and ebook production was changing. I no longer needed someone in the office. With Canva, I found that I could often just create professional-quality graphics myself, for my own work and the Train Campaign. (Admittedly, we’d already come up with a lot of basic artwork and color palettes.) I can’t do everything, of course, but I’m continually stunned by how this particular app has let me be more creative, and more efficient.

Canva is continually being improved. It’s an impressive piece of engineering, easy and fun even for a beginner, and free for educators and nonprofits.

My apologies to readers outside the US. Some of my recommendations won’t work for you. Please let me know if there are similar things in your part of the world, and if you’re interested in particular items, I’ll be glad to see what I can suggest. I’ll be putting a lot of emphasis on things that help us to reduce pollution, waste, and our carbon footprint, in the spirit of home ecology.

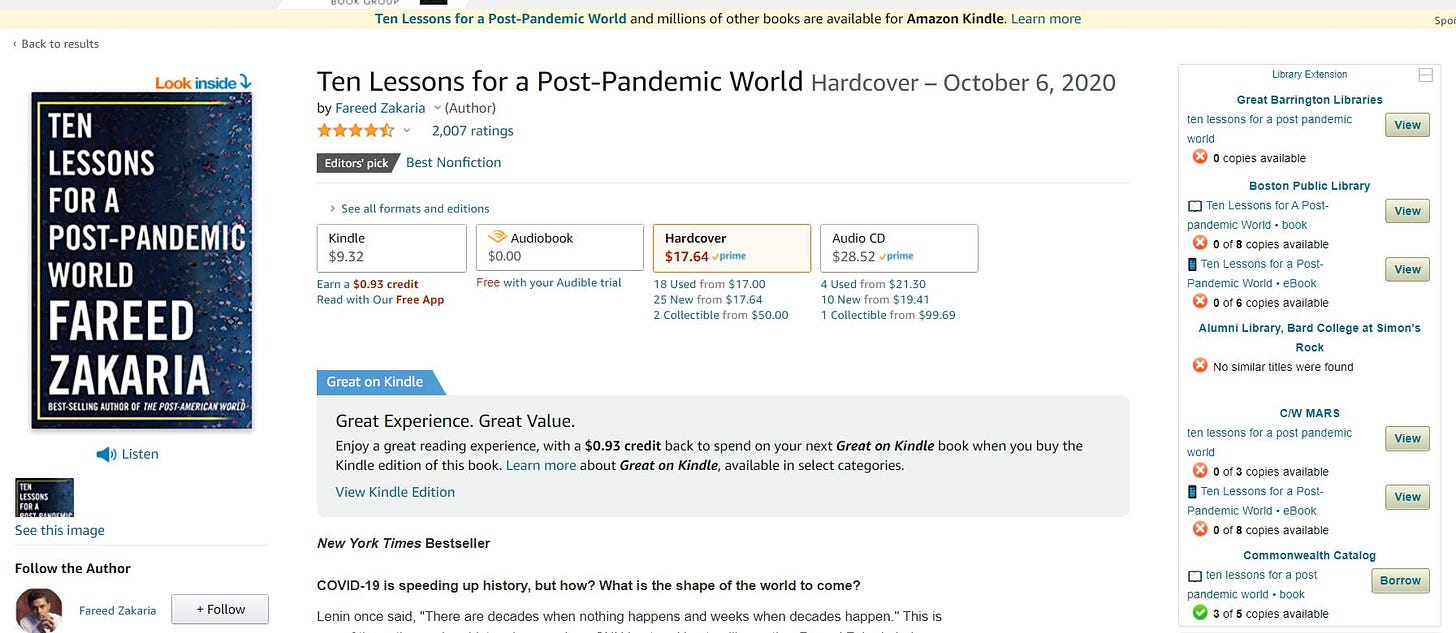

Library Extension

I rely on the Chrome Library Extension plug-in, which works on Amazon and Barnes & Noble book pages (and maybe others). As you can see, when I look up a book, it searches for the title in the catalogs of the libraries I routinely use. I can click on the Borrow link and place a hold.

A year ago, I had a houseful of Chinese cuisine experts and we were cooking up all kinds of delicious things. With the 2021 Lunar New Year coming and China on my mind, I was happy to receive a new review of The Way of Eating:

Exceptionally well written, organized and presented, The Way of Eating: Yuan Mei's Manual of Gastronomy is an inherently fascinating and informative read. An extraordinary and unreservedly recommended addition to professional, community, college, and university Food History collections in general, and Chinese Cuisine History reading lists in particular. It is also readily available in a paperback edition (9781614728276, $29.95) and in a digital book format (Kindle, $9.95). —Midwest Book Review

Available from Berkshire Publishing’s website here. Paid subscribers to Karen’s Letter get the ebook free.

Who knew?

Patch Adams book lists

I was looking for books about city planning and community design and found these remarkable book lists, and many more, on the website of an institute founded by Dr. Patch Adams, whose name I knew only because of the Robin Williams movie. Eclectic, indeed, with plenty of books I’d never heard of. Here are two of them: Chinese Literature and Architecture and Community . There are lots more.

Crown shyness

This video of trees dancing is the most beautiful thing I’ve ever found on Twitter. It’s headlined with “Trees that ‘social distance’” but really it’s just magical to watch. The explanation is that “Many forest canopies maintain mysterious gaps, called crown shyness, that could help trees share resources and stay healthy.”

Windows on the world

It was also fun to discover that we can actually enjoy other people’s points of view with Windowswap.

Now I’m going to listen to “Don’t Worry, Be Happy.” Have a great weekend!

I think there were four reasons why the Spanish Flu had so little impact afterwards:

1. Death was more common and was just accepted. For example the huge number of deaths in early childhood and from TB. There may have been an interaction (both ways) here with a higher level of religious faith. Nowadays we are less familiar with death and regard the possibility of it with greater horror.

2. The horror of the war may have taken precedence and to some extent the two horrors may have become merged in peoples’ minds. To say nothing of (e.g.) the Russian revolution. We have not had a major war this time (fortunately).

3. After both the war and the flu, people just wanted to forget about them, but the remembrance of the war was more formalised. It is striking that there are no memorials to the flu dead in contrast to the huge number of war memorials. Yet there is already talk here of a memorial to the Covid dead. It has been said that the frivolity and fast pace of life in the 1920s may have been a reaction to both horrors.

4. The mass media was much more limited in 1918, not least because of wartime censorship, and there was no rolling news, no internet news or social media. And the flu was much less prominent in the news than Covid now. On the BBC I reckon that Covid is always the first five items and at least 75% of the total newscast. Very different!

You wonder about the US in particular. Relative to the other factors I mention, I am not sure the larger number of deaths in itself is a factor (although it must play some role). Here in the UK and Europe generally, the death tolls in the flu pandemic were very high and Covid deaths (relatively speaking) are high too. But we are obsessing much more about Covid than our ancestors did about the flu over here too. I think part of it is the greater social and economic impact of Covid, there were no lockdowns in 1918!

As an historian who writes about complex historical systems and nonlinear dynamics, I can offer two of my recent publications, which reflect a multidisciplinary funding proposal I had hoped to submit to the U.S. National Science Foundation. The pandemic crushed that idea.

On a means to grasp the complexity of the First Global Age, 1400-1800:

* J. B. Owens and Vitit Kantabutra (2020) “A Research Scheme for a World History of the World,” Entremons. UPF Journal of World History. Número 11 (Octubre): 69-98.

(Universitat Pompeu Fabra | Barcelona)

The companion piece is a research report, which I intended to use to identify and recruit collaborators for the project. It deals with "local" non-linearity, which must be connected (via modeling) to the global complex, nonlinear system:

* J. B. Owens (2019) “If I Forget Thee, O Murcia,” Newsletter: Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies. Vol. 10 (November): 5-15.

I hope that you find something of interest in this post.

Jack Owens