Can Poetry Change the World?

The centenary of The Waste Land has made me take a new look at the magic of poetry.

Are you afraid of poetry? I am.

This is true even though the first money I made as a writer was five cents for a poem. My best friend, age ten, was entrepreneurial. She decided to sell my poems by going door to door in the neighborhood and was triumphant when Mrs. Johnson handled over a nickel. We then realized we needed more copies of the poem to continue and decided to stop while we were ahead.

I was taught to write critically about poems for the Oxford Entrance Exams. I took classes on 17th-century and modern poetry at UC Santa Barbara. I have a long shelf of poetry books I can’t bring myself to throw away, and on my bedside table I have a tiny edition of Palgrave’s Golden Treasury as well as a collection of Chinese poems. But I rarely read poetry now.

This might change in 2022 thanks to Qiu Xiaolong, T. S. Eliot, and Stephen Fry.

Yes, Stephen Fry, the English actor, broadcaster, comedian, and writer. He has written a book called The Ode Less Taken: Unlocking the Poet Within. The book is about writing poetry, which he does for relaxation and pleasure, the way other people play chess, or sing in a choir, or paint.

I have written this book because over the past thirty-five years I have derived enormous private pleasure from writing poetry and like anyone with a passion I am keen to share it. You will be relieved to hear that I will not be burdening with any of my actual poems (except sample verse specifically designed to help clarify form and metre): I do not write poetry for publication, I write it for the same reason that, according to Wilde, one should write a diarv, to have something sensational to read on the train. And as a way of speaking to myself. But most importantly of all for pleasure.

Modern readers are taught to treat poems as if they were crossword puzzles.

We have all of us, all of us, sat with brows furrowed feeling incredibly dense and dumb as the teacher asks us to respond to an image or line of verse.

What do you think Wordsworth was referring to here?

What does Wilfred Owen achieve by choosing this metaphor?

How does Keats respond to the nightingale?

Why do you think Shakespeare uses the word 'gentle' as a verb?

Yet great poets seem to be able to transcend boundaries, to find a way to speak to us without need of explanation, or explication.

That’s why I’ve decided not to include any notes in the 100th anniversary international edition of The Waste Land we’ll be publishing in a couple of weeks. My academic friends thought I should commission additional material to explain its many references and allusions. But it seems to me more important to present the poetry in a beautiful edition designed to be read and enjoyed, to let readers experience Eliot’s work directly, as what Ezra Pound, also a famous poet, called “an emotional unit.”

T. S. Eliot wrote in Burnt Norton, as if addressing his lost lover, “My words echo | Thus, in your mind.” And his words have echoed through the decades for many readers, including novelist Qiu Xiaolong (more about him below), who has written a marvelous introduction to our edition.

Making the world a better place

It seems to me that our time requires us to stretch our wings, to be more creative and innovative. Here’s what Fry says:

We don't stop talking about how the world might be better just because we have no chance of making it to Prime Minister. We are all politicians. We are all artists. In an open society everything the mind and hands can achieve is our birthright. It is up to us to claim it.

And you know, you might be the real thing, or someone with the potential to give as much pleasure to others as you derive yourself. But how you will ever know if you don't try?

I often wish I’d been taught to look at the techniques used by the authors of the great novels I read in college, and now realize that we never talked about the structure and methods used by the poets either. Engineering is far too often neglected!

This promise from Fry made me feel a bit guilty:

I cannot teach you how to be a great poet or even a good one. Dammit. I can't teach myself that. But I can show you how to have fun with the modes and forms of poetry as they have developed the years. By the time you have read this book you will be able to a Petrarchan sonnet, a Sapphic Ode, a ballade, a villanelle and a Spenserian stanza, among many other weird and delightful forms; you will be confident with metre, rhyme and much else besides.

I felt guilty because I never appreciated the work required to produce the seemingly endless stream of poems that a long-ago lover once wrote for me. They were enclosed with letters that came from New York almost every day. I would run downstairs when I heard the clang of the letterbox at 6am in a Devon village. I poured over the letters and of course read the poems. But he must have been disappointed when I didn’t recognize the complex forms he had so carefully worked. (Years later I found that he had published them.)

Making this a very long letter, I’d nonetheless like to share some poems in the hope of enticing you to reconsider poetry. And if you are already someone who loves poetry and reads it regularly, please do send some recommendations.

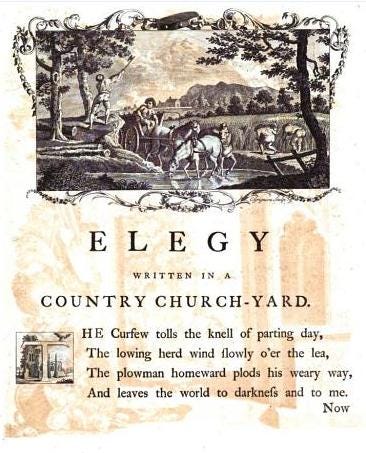

This is part of one of my favorites, one of the best-known of all poems in English:

From Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard Thomas Gray (1716–1771) ...Perhaps in this neglected spot is laid Some heart once pregnant with celestial fire; Hands, that the rod of empire might have sway'd, Or wak'd to ecstasy the living lyre. But Knowledge to their eyes her ample page Rich with the spoils of time did ne'er unroll; Chill Penury repress'd their noble rage, And froze the genial current of the soul. Full many a gem of purest ray serene, The dark unfathom'd caves of ocean bear: Full many a flow'r is born to blush unseen, And waste its sweetness on the desert air. Some village-Hampden, that with dauntless breast The little tyrant of his fields withstood; Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest, Some Cromwell guiltless of his country's blood. Th' applause of list'ning senates to command, The threats of pain and ruin to despise, To scatter plenty o'er a smiling land, And read their hist'ry in a nation's eyes, Their lot forbade: nor circumscrib'd alone Their growing virtues, but their crimes confin'd; Forbade to wade through slaughter to a throne, And shut the gates of mercy on mankind,…. [read the rest]

Try reading the entire poem aloud! It is wonderful to read, and its content is fascinating. The usual explanation is that it celebrates unknown people and says that death comes for all, rich or poor. But for me, reading it today, there’s a much more interesting point. Those unknown rural folk might have had world-changing talents. Perhaps one would have been another Milton, or a great composer. Or we may be lucky that a village tyrant lived and died in obscurity, when he might have become a villain on a larger stage.

What strikes me is how democratic this was: the poet recognized that chance of birth generally determines our possible futures, and understood that the seed of genius may well be found in people of humble birth. In a society where class distinctions were of utmost importance, this was bold. Perhaps it accounts for the unexpected success of the poem, a publishing story worth reading if you’re curious about the challenges authors faced in the 18th century.

Remember, Remember

“Remember, remember the Fifth of November” is a familiar phrase in Britain, and neighborhood bonfire night was one of the things I missed most after moving back to the US. I thought of it a few weeks ago, on the Sixth of January, which is should be a lovely end of the Christmas season, a day of gifts called Epiphany and the day the Christmas tree comes down. But now, for us in the US, January 6th is tarnished, a day of infamy that indeed we will remember.

A lot of people know the phrase from the movie V for Vendetta, which Stephen Fry starred in. But I’ll bet not many people know where it comes from—a truly surprising source indeed: the poet John Milton, blind author of Paradise Lost, a writer whose name is often mentioned along with Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Austen.

This poem is a early work, not very memorable—except that his first few lines are memorable indeed! It’s the rhythm and the rhyme, of course. But don’t we also instinctively grasp that terrible events, as well as happy ones, should be remembered?

“In Quintum Novembris” (“On the Fifth of November”)

By John Milton, 1626

Remember, remember the Fifth of November,

The Gunpowder Treason and Plot [of 1605],

I know of no reason

Why the Gunpowder Treason

Should ever be forgot.

Guy Fawkes, Guy Fawkes, t'was his intent

To blow up the King and Parli'ment.

Three-score barrels of powder below,

Poor old England to overthrow;

By God's providence he was catch'd

With a dark lantern and burning match.

Holla boys, Holla boys, let the bells ring.

Holloa boys, holloa boys, God save the King!

And what should we do with him? Burn him!

Remember, remember, the 5th of November,

Gunpowder, treason and plot.

I see no reason

Why gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot.

Guy Fawkes, Guy Fawkes, 'twas his intent

To blow up the King and the Parliament

Three score barrels of powder below

Poor old England to overthrow

By God's providence he was catch'd

With a dark lantern and burning match

Holler boys, holler boys, let the bells ring

Holler boys, holler boys

God save the King!From Jane Eyre, 1847

“I have brought you a book for evening solace,” and he laid on the table a new publication—a poem: one of those genuine productions so often vouchsafed to the fortunate public of those days—the golden age of modern literature. Alas! the readers of our era are less favoured. But courage! I will not pause either to accuse or repine. I know poetry is not dead, nor genius lost; nor has Mammon gained power over either, to bind or slay: they will both assert their existence, their presence, their liberty and strength again one day. Powerful angels, safe in heaven! they smile when sordid souls triumph, and feeble ones weep over their destruction. Poetry destroyed? Genius banished? No! Mediocrity, no: do not let envy prompt you to the thought. No; they not only live, but reign and redeem: and without their divine influence spread everywhere, you would be in hell—the hell of your own meanness.”

Chinese Poems

I can’t conclude without mentioning Chinese poetry. Qiu Xiaolong—novelist, poet, translator of T. S. Eliot as well as of Chinese poetry, and a friend with whom I’ve collaborated on the new edition of The Waste Land—weaves poems into his latest novel and even includes some of them at the end.

This latest of his bestselling detective stories is set within the world of Tang dynasty poets. The starred review in Publishers Weekly says, “Qiu combines a sophisticated puzzle with appropriate period detail, avoiding the anachronisms of previous Judge Dee fiction. Fans of those books, by Robert van Gulik and others, will clamor for more.” Here’s one of his own translations:

To Wen Tingyun

By Yu Xuanji (84-871)

The crickets chirruping in confusion

By the stone steps, the crystal-clear

Dewdrops glistening on the tree leaves

In the mist-enveloped courtyard,

The music floating from the neighbors

Under the moonlight, I look out, alone,

From the high tower to the far-away view

Of the lambent mountains. The wind chilly

On the bamboo mattress, I can only express

My sadness through the decorated zither.

Alas, you are too lazy to write a letter

To me. What else can possibly come

To console me in the autumn?And with Spring Festival (the Lunar New Year) only a few days away, here is another poem, sent today by my friend ZHAO Wuping 赵武平 at Translation Press in Shanghai:

Flowering Crabapples

By Su Shi (1037–1101)

With full spring in the air blew a gentle breeze east,

The moonbeam turned around the porch in a sweet moist mist.

Fearing the flowers would go to sleep towards deep night,

I burnt thick candles aloft to shine the beauties bright.

《海棠》 苏轼

东风袅袅泛崇光,香雾霏霏月转廊。

只恐夜深花睡去,更烧高烛照红妆。Democracy

On January 6th, my brother Jim found this banner on the shore of Vashon Island, near Seattle. “Is democracy all washed up?” he quipped. I prefer to see it as a good omen. We talk and write a lot about democracy now, but what have poets written? Here is a poem by Langston Hughes, a founder of the Harlem Renaissance.

Democracy

By Langston Hughes (1901-1967)

Democracy will not come

Today, this year

Nor ever

Through compromise and fear.

I have as much right

As the other fellow has

To stand

On my two feet

And own the land.

I tire so of hearing people say,

Let things take their course.

Tomorrow is another day.

I do not need my freedom when I'm dead.

I cannot live on tomorrow's bread.

Freedom

Is a strong seed

Planted

In a great need.

I live here, too.

I want freedom

Just as you.

I've been thinking about my relationship with poetry a great deal recently. I've read poetry, studied poetry, written poetry (badly), taught poetry (somewhat less badly), and I am fascinated by how the most common route for adults into poetry is through writing it.

I know poetry publishers who receive submissions from writers who are genuinely astonished when it is suggested that they might like to read and even (good heavens) buy the work of other poets.

To my mind, reading poetry is a creative act in itself, because poetry is so dependent on the ambiguities of language. Reading poetry is co-creation, and I think more needs to be done to recognise, celebrate and promote this. (For example, in England, the Arts Council does not consider readers as "audience" or participants in the arts.)

I find that as I walk, lines of poetry I didn't know I knew float through my mind. (my father used to say he didn't learn poetry, poetry learned him). In particular, when I think of politics, lines from WH Auden flood in. Thinking of the current mess in Downing Street, I hear... "Caesar's double bed is warm/ As an unimportant clerk/ writes I DO NOT LIKE MY WORK/ On a pink official form...' (Fall of Rome).

I'll leave it there for now, but would be interested in hearing more about why people read poetry. (I have a project brewing ...)

I think it is very interesting and coincidental that you talk about the waste land and then after that put some lines from Elegy in a country churchyard.At one stage TSE mentioned that he wanted to write a poem as good as Elegy in a country churchyard. This was before 1922.