The coming year is the Year of the Snake, but the snake does not seem to be a popular animal judging by the greetings I’ve received. In the Chinese zodiac, bulls and dragons are popular, and even mice (or rats) have their fans. But even our friends in Asia seem to shy away from the snake. In Judeo-Christian tradition, too, it was the serpent who tempted Eve, and snakes always seem to be dangerous or sly.

I’ve never been afraid of snakes, after growing up with a father who thought we should fill the garage and playroom with tubs of wild creatures. We even had a snake that gave birth in an old aquarium. The letter is an attempt to put a few good words for these elusive creatures!

I’ve been hoping for a Lunar New Year card with an image of snakes in a bottle, immersed in wine and considered an exotic medicine in Asia. A row of bottled snakes, including cobras, is a memorable sight in any Chinese herbal medicine shop or even some drugstores. My son brought a bottle home from our first trip to China as a gift for his high-school biology teacher, who accepted it with some reluctance since 15-year-old Tom really shouldn’t have been carrying wine into the school. I’ve also seen snake-oil hand-cream, and snake is not uncommon on menus. I took this photo at a market in Guangzhou.

Endangered snakes

Snakes, like other wild creatures, have suffered from human construction and pollution, and should be encouraged and protected—even rattlesnakes, which get a bad rap. They live in the mountains in western Massachusetts as well as out west, but less and less common, as are the other snakes and amphibians listed on wildlife websites like this one: Mass Audubon Snakes and Save the Snakes. Even the garden-variety snake species are beautiful, and they play a vital role in global ecosystems. Their decline is part of the overall decline in vertebrate biomass. “We are eroding the very foundations of our economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide,” as you can read here. Biodiversity loss and climate change are intertwined problems. Indeed, let’s save the snakes!

In some parts of the world, venomous snakes are more common, but in Massachusetts there has not been a fatal rattlesnake bite, I’ve just read, since 1791 (and I have not transposed the numbers). Surely we need to reconsider our fears, and do more to encourage all the useful species that used to inhabit our lawns and gardens.

Last summer a snake came to take a look at the food supply in my little pond. I saw it only after puzzling for several minutes about a shrill bleating that came from that direction. The bleating came from a fairly large frog that was being devoured, slowly, by a not to large garter snake. It was pathetic to watch but I nonetheless couldn’t resist getting a photo. if you’re not squeamish, there’s a (blessedly short) clip at my pond-life YouTube channel, along with some fun frog videos. Ever wonder how frogs make love? And war? You’ll get the picture here.

The following week the snake came circling the pond, and as it went round the frogs, one after the other, plopped into the water. Garter snakes can swim and hunt in the water, but I never saw this one again. Hoping for more this summer. I do not like having my frogs eaten, but it’s neat to see the backyard ecosystem evolve.

A Chinese snake story

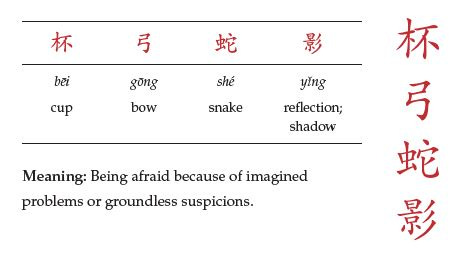

Bei gong she ying 杯弓蛇影

This proverb lesson was written by our friend Haiwang Yuan, and is included in Becoming a Dragon. I wanted to show this today because is a good example of the way the Chinese language works, the layers of allusion and storytelling that go into common expressions.

A chengyu, for example, is a standard kind of proverbial expression consisting of only four characters. They remind me of William Blake’s poem:

To see a World in a Grain of Sand And a Heaven in a Wild Flower Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand And Eternity in an hour . . .

A literal translation of the snake proverb is “cup - bow - snake - reflection.” Together they have a rich meaning, similar to our English phrase, “Being afraid of one’s own shadow.”

Here is Haiwang’s telling of the story:

During the Jin dynasty, there was a man named Yue Guang. He was rich and liked to make friends. He took great delight in inviting his friends home drinking and chatting. One day, Yue Guang entertained a friend at his home again. After a sip, the friend was about to replace his wine cup on the table when he paused. To his horror, he found a little snake wriggling in the cup he was holding. However, he was too shy to tell Yue Guang about it. Instead, he gave an excuse that he did not feel well and left for home after saying goodbye.

At home, the friend tried to recollect what had happened but the more he thought of the sight of the snake, the more scared he became. Soon he worried himself to illness. Upon hearing of his friend’s condition, Yue Guang came to see him and asked what on earth had caused him to become sick. At first, the friend hesitated, but after repeated prodding from Yue Guang, he finally let out the truth: he told Yue Guang that he was scared to illness by the snake he had seen in the wine cup while they had been drinking together at Yue Guang’s home the other day.

As soon as he returned home, the baffled Yue Guang singled out the wine jar from which he had drunk with the friend. He shook it vehemently several times and peeped hard into the mouth, but he failed to find anything but the wine left over therein. He poured it into a cup and sat melancholy where the friend had been seated. He was about to drink when he became alarmed like the friend: a snake was floating in the cup indeed. Rubbing his eyes, he took a closer look and, with a relief, came to the realization that the snake was nothing but a reflection of the bow hanging on the wall nearby.

Click here for the 4-page lesson in English and Chinese.

Wishing you courage, resilience, and flexibility in the Year of the Snake!