Civic Life, a history - Part II

How the early media helped develop a democratic public life

Part I explained how the idea of a public sphere - of civic and public life as citizens - originated, with the Greeks, and then reemerged in late medieval Europe (circa 1300) in newly formed city-states. Global trade made necessary the establishment of legal systems, and with law came rights—first the rights of the city-states, then the rights of the guilds (associations of merchants), and eventually the rights of citizens themselves. Part II continues the history and then discussesd various ways of looking at civic life today (with a focus on the United States). The writing of both Robert Bellah and Robert Putnam get attention, connecting the idea of civic life with social capital and community building.

Part I is here:

Civic Life - Part II

From the Encyclopedia of Community, ed. Christensen & Levinson. Article by Lewis A. Friedland and Carmen Sirianni

Continued…

The Age of Revolution and Modern Civil Society

The Enlightenment was that great period from the late seventeenth century through the French Revolution of 1789 during which time modern Western ideas of freedom, liberty, individual rights, and the proper relation between state and civil society emerged.

The Enlightenment begins politically with the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, which established the principle (if not practice) of religious toleration in Europe. Toleration, in turn, planted the seed of the idea of separation of church and state, the principle that citizens should be politically free to believe as they wish and that no one church should be favored by the state.

The gradual separation of the state and civil society, along with the growth of a modern public sphere, are the pillars on which modern civic life rests. The early modern state witnessed the distancing of the household of the monarch from the government. In other words, the king or emperor no longer directly controlled the national purse or exercised direct personal power over the national military. Treasuries, taxation, law, and the maintenance of public order slowly were separated from royal whim. During the English Civil Wars (1642<N>1651) Charles I was executed and Parliament became the ruling power in the nation. The monarchy was restored in 1660, but in 1688, when William and Mary took the throne, they did so as constitutional monarchs, not absolute monarchs, and the principle of the separation of king and government was firmly established. In France, separate parlements, or courts of law, grew slowly in power from about the mid-sixteenth century through the revolution of 1789, in which the Estates General established a constitutional monarchy (shortly thereafter overthrown by the revolutionary republic). In the New World, the revolution of 1776 founded the first original constitutional government in 1787<N>1788. Regardless of national differences, the broad principles of the modern state were held in common: The state was separate from the personal rule of king or president; the state’s powers were limited; the state was governed by laws. Henceforth the state sphere was also separate from the sphere of civil society.

Civil Society and the Public Sphere

Civil society grew up alongside the modern state. Writing about civil society in The Leviathan (1651), the political theorist Thomas Hobbes (1588<N>1679) said, in part in reaction to the English Civil Wars, that civil society created the state to protect citizens one from another, to end the war of “each against all.” In Hobbes’s view, the state ensured order in civil society, which resembled anarchy. By contrast, the philosopher John Locke (1632<N>1704) wrote in his Two Treatises on Civil Government (1690) that civil society grew from a state of nature, but through the social contract created the state for its protection, and thus could dissolve it when it failed to serve and protect the community. The German philosopher Georg Hegel (1770<N>1831) drew from ancient Greece, seeing civil society as a community of citizens who agreed on what it took to live the good life and created civil society to realize that vision. He saw the state as embodying and protecting both civil society and the vision of the good life. All three theorists held that civil society was a sphere apart from the state.

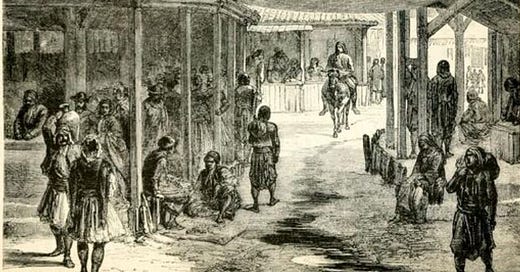

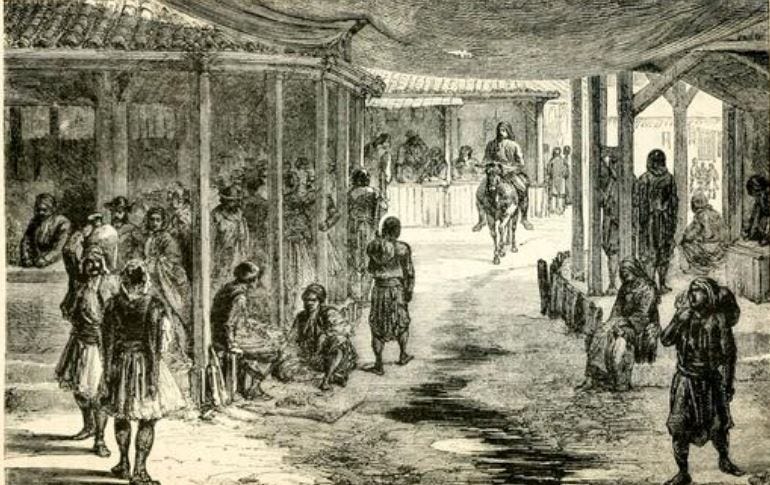

The modern public sphere, for its part, grew up in the eighteenth century between civil society and the state, and mediates between them. In coffeehouses and salons, through newspapers and journals, and through associations and small assemblies, citizens came together to reason about politics, the state, literature and art, and the family. They argued about how these institutions should be constructed and what should be the proper limits of their power. Private citizens, or bourgeoisie (which originally meant simply independent city dwellers or burghers), were also property owners competing in the marketplace. But at the same time, through their discussions in the public sphere, they laid the groundwork for the most important rules and rights of a liberal society: the rights of free speech, assembly, and press, as well as the more fundamental rights of the individual that guaranteed these social rights. According to the contemporary German philosopher Jürgen Habermas, the public sphere embodied the democratic principles of modern society, protecting society both from the domination of the emerging industrial marketplace and from the power of the state.

The great revolutions at the end of the eighteenth century tied together these various ideas of the state, civil society, and the public sphere in different ways. In France, the Revolution of 1789 overthrew the emerging constitutional regime and led to the Reign of Terror and the Napoleonic empire, neither models of open civil society and public life. In the case of France, the state overwhelmed civil society. In England, the constitutional monarchy offered one evolutionary model, but one in which the economic engine of civil society, unconstrained industrialization, seemed to overwhelm a democratic public sphere (although opposition parties continued to participate in public life). The United States was a model rife with the contradictions. Although slavery continued in the South and propertied elites existed everywhere, the nation was founded on the very ideas of civil society and civic life<M>that citizens could act together, blending self interest and the common good, to regulate both society and public life. For the sake of providing an in-depth analysis of civic life in one country rather than an overview of civic life in many, this article now turns to focus on the United States.

Civic Life and the Early-Nineteenth-Century United States

The great observer and theorist of U.S. civic life in the early nineteenth century was Alexis de Tocqueville (1805<N>1859). He came to the United States in 1831 to observe the underlying conditions of U.S. democracy. His work, Democracy in America, published in two volumes in 1835 and 1840, continues to set the frame for much of the discussion of civic life in the United States even today. In contrast to those who saw a radical distinction between state and civil society in Europe, Tocqueville observed a close relation between the two in the United States. He saw democracy as governed by public opinion, arising out of the opinions of individuals freely associating with one another in civil society. Therefore for Tocqueville the civic life of associations was the very essence of democratic life in the United States, and, because Tocqueville saw the United States as a model of modern democracy, elsewhere as well.

In a famous passage, Tocqueville describes the civic life of the United States in all of its richness:

Americans of all ages, all conditions, all minds constantly unite. Not only do they have commercial and industrial associations in which all take part, but they also have a thousand other kinds: religious, moral, grave, futile, very general and very particular, immense and very small; Americans use associations to give fêtes, to found seminaries, to build inns, to raise churches, to distribute books, to send missionaries to the antipodes; in this manner they create hospitals, prisons, schools. Finally, if it is a question of bringing to light a truth or developing a sentiment with the support of a great example, they associate. Everywhere that, at the head of a new undertaking you see the government in France and a great lord in England, count on it that you will perceive an association in the United States. .

In short, Americans associated to do things: worship, celebrate, and think together; to govern the town, care for the sick, and imprison the criminal. Associational life for Tocqueville was not altruistic, in the sense that voluntarism connotes today. Association was linked with self-interest and getting the real work of society and government done. It is a powerful notion of a civic life that has real and direct consequences in the world.

The Tocquevillian View Reassessed

In the 1990s U.S. scholarship began to expand, interpret, and, in some cases, challenge the classical Tocquevillian view. There are three broad areas of reinterpretation. The first reinterprets the problem of individual and community. The second challenges the political image of harmony. The third explores whether early U.S. civil society was, in fact, as rooted in local community life as Tocqueville believed.

The scholar Robert Bellah and his coauthors of the modern sociological classic Habits of the Heart (1996) argue that it is particularly difficult to sustain community in the United States because individualism, “the first language in which Americans tend to think about their lives, values independence above all else” (p. viii). Individualism takes two forms. One is utilitarianism, the belief that if everyone vigorously pursues his or her own interest the social good will automatically emerge; the other is expressive individualism, which stresses the exploration of self-identity and the search for authenticity above all else. According to Bellah, this individualism has been sustainable in the United States only because people are also guided by an ethos of commitment, community, and citizenship. In Habits these principles are gathered under the rubric of “civic membership,” the intersection of personal identity with social identity. Bellah and colleagues were among the first to warn that, despite Tocqueville’s vision, civic membership is in crisis, reflected in “temptations and pressures to disengage from the larger society” felt by every significant social group (xi).

The historian Mary Ryan is among those scholars who have shown that civic and public life in nineteenth-century U.S. cities was much more fractious and chaotic than the Tocquevillian image. Ryan shows that civic life in New York, New Orleans, and San Francisco grew from the mingling of many different types of people in the streets, large public ceremonies, parades and processions, as well as the skirmishes between different ethnic and racial groups. The partisan elections of the nineteenth century, she argues, were bare-knuckle fights to the death among party machines, nothing like the image of public life offered by Tocqueville. The sociologist Michael Schudson also claims that the civic ideal of the Founding Fathers was one of elite rule<M>civic life consisted, in part, of accepting the decisions of one’s betters. This “politics of assent” gave way to a “politics of affiliation” in which membership in a political party defined one’s civic and political identity through much of the nineteenth century: Partisanship replaced hierarchy.

The third debate about the growth of civic life in the nineteenth century revolves around the question of how much civic life grew from below, grassroots-style, and how much it was founded from above by large national organizations that paralleled the federal political structure of the United States. The scholar Theda Skocpol and her colleagues, drawing from “Biography of a Nation of Joiners” (1944), the seminal article by the historian Arthur Schlesinger, claim that early U.S. civic life was more closely tied to the federal structure of U.S. government than Tocqueville implies. They point to antislavery, Christian, fraternal, and temperance associations that began as national organizations and spread to local communities. They point out that after the Civil War, this federal model was responsible for the growth of major national organizations, whether farmers’ alliances and veterans’ organizations, the labor and women’s suffrage movements, or youth organizations and even bowling congresses. They also contest the idea that industrialization, urbanization, and immigration in the latter nineteenth century were as important in creating new associations in the cities as historians have previously believed.

But virtually all scholars agree that the second half of the nineteenth century saw the birth of major civic organizations in the United States, many of which persisted well into the twentieth century, eventually reaching into almost every city and town in the country.

The Progressive Era to the Present

The Progressive Era (c. 1900<N>1915) arose in the beginning of the twentieth century in part in opposition to the tumultuous, partisan street democracy of the nineteenth century. Against the urban machine, it posed the ideal of scientific government, of rule by those capable of enlightened public opinion and scientific management. The ideal citizen was a middle-class reformer, still a member of associations, but associations of a new kind. Among the U.S. associations born out of the Progressive Era are the National Civic League, the League of Women Voters, parent-teacher associations, and organizations for youth such as the Boy Scouts and the Girl Scouts. The fraternal lodges of the nineteenth century were overshadowed (but not replaced) by the new business associations such as the Rotary and Lions Clubs. The Progressive Era saw the growth of unions, settlement houses, and kindergartens, as well as the emergence of the “social congregation” in the churches. Extension schools at the University of Wisconsin and elsewhere spread the ideal of knowledge in the service of the public good throughout the states. The Progressive Era also challenged certain ideals of participation. The ideal of the “informed citizen,” to use Schudson’s phrase, replaced the partisan citizen, but shift also entailed a restriction of the civic franchise.

Despite its shortcomings, the sociologist and political scientist Robert Putnam sees the Progressive Era as the starting point of a great wave of civic innovation in the twentieth-century United States that only began to wane in the 1960s. His research has been at the center of the argument over the decline of U.S. civic life in the twentieth century. Putnam argues that our stocks of “social capital” (defined as the norms and networks that people can draw upon to solve common problems) have been depleted. Many measures of associational membership in the United States have been in decline since the early 1970s. Participation in religious congregations, a bedrock of association in the United States, declined by one-fifth between 1980 and 2000. Memberships in parent-teacher associations and organizations has plummeted since the 1960s. Union membership has fallen by half since the 1950s. Women’s organizations such as the League of Women Voters and General Federation of Women’s Clubs have seen 40<N>60 percent declines. And membership in fraternal and business clubs has also dropped. More worrisome for Putnam is the decline in active participation in these organizations. He estimates that the active core of the United States’ civic organizations, those who serve as officers and committee chairs, declined by 45 percent from 1985 to 1994 . According to Putnam, America lost nearly half of its civic infrastructure in less than a decade.

While scholars do not agree on the reasons for this decline, there is some basic agreement on certain trends. The number of self-help groups has risen dramatically in this same period, suggesting a shift from civic concerns to personal self-fulfillment. Television watching has risen dramatically, and the Internet was born, suggesting a shift from face-to-face participation to media consumption. Women have entered the labor force in ever growing numbers, eroding the volunteer labor that sustained school and community-based association for much of this century. And suburbanization and associated sprawl have eroded communities of place. All of these trends are combined with a huge grown in professionalized, direct-mail, national organizations with little or no active membership. Putnam also posits a major generational shift, as the “long civic generation” that grew up during the Depression and World War II is replaced by Baby Boomers and Gen X and Gen Y cohorts, with each successive generation less and less involved in civic life. The causes behind these generational declines are unclear, but the larger trend towards disengagement from civic life in the twentieth century seems indisputable.

Some scholars have questioned whether the picture is as stark as Putnam suggests, however. Americans continue to volunteer at extraordinarily high levels, and some researchers have argued that participation may actually be increasing at the local community level. Robert Wuthnow argues that the new wave of self-help groups help form loose connections that may create new forms of social capital.

Causes and Countertrends in the United States

Scholars and citizen-practitioners differ on what might be done to reverse the decline in U.S. civic life. Putnam stresses that rebuilding social capital is a difficult task, and is modest in his suggested solutions. In the final chapter of Bowling Alone (2000), he suggests that finding new ways to reengage young people is the most important starting place, including developing civic curricula in schools to show how young people can become more engaged and creating more-effective programs of community service. He also calls for more family-friendly policies in the workplace to create more time for community and suggests finding ways to redirect attention from television. He hopes the Internet can be used to encourage more-active forms of civic communication, including more participation in local arts, and he supports reversing sprawl and getting more Americans engaged in local politics. He also suggests a socially responsible and pluralistic “great awakening” among the United States’ religious communities.

There is substantial agreement with much of this program among other critics of declining civic life, but there are differences as well. Communitarians such as Amitai Etzioni claim that a breakdown in the moral fabric of society and excessive individualism in the public sphere have led to civic decline; they call for a new social philosophy that would protect individual rights while emphasizing community responsibility. Communitarians claim to stake out a middle ground between left and right. They share some affinities with conservative critics of civic decline, who see a sharp contrast between the potentially rich civic life of “mediating institutions” in local neighborhoods and communities on the one hand and government on the other. Drawing from thinkers like Michael Novak and Robert Nisbet, they claim that the civic functions of community have migrated to government, and that it will be necessary to reverse this trajectory both by rebuilding local civic life and by shrinking government.

On the left, Theda Skocpol and her colleagues suggest a need to revive a model of the federal organization of civic life that led to the founding of so many civic organizations in the nineteenth century. Skocpol and others argue that Washington-based interest groups have displaced the multitiered structures of the earlier period, and that this trend must be reversed. Skocpol also believes that revitalizing the U.S. Democratic Party is a necessary component in renewing the nation’s civic life.

Finally, the scholars Carmen Sirianni, Lewis Friedland, Harry Boyte, and leaders of various organizations such as the National Civic League and Campus Compact are endeavoring to build a broad and nonpartisan civic renewal movement on the foundations of the extensive civic innovations and community-building networks that have emerged in recent years. This approach stresses that the work of civic renewal needs to go on not just in civil society, but in government, market, educational, and professional institutions of all sorts. This requires an expansive view of the productive public work of all citizens in building the commonwealth. It stresses pragmatic problem-solving skills rather than exhortation. And it stresses reliance on a multiplicity of forms of civic partnership rather than on an ideal model from the past.

—Lewis A. Friedland and Carmen Sirianni