Hard truths about publishing

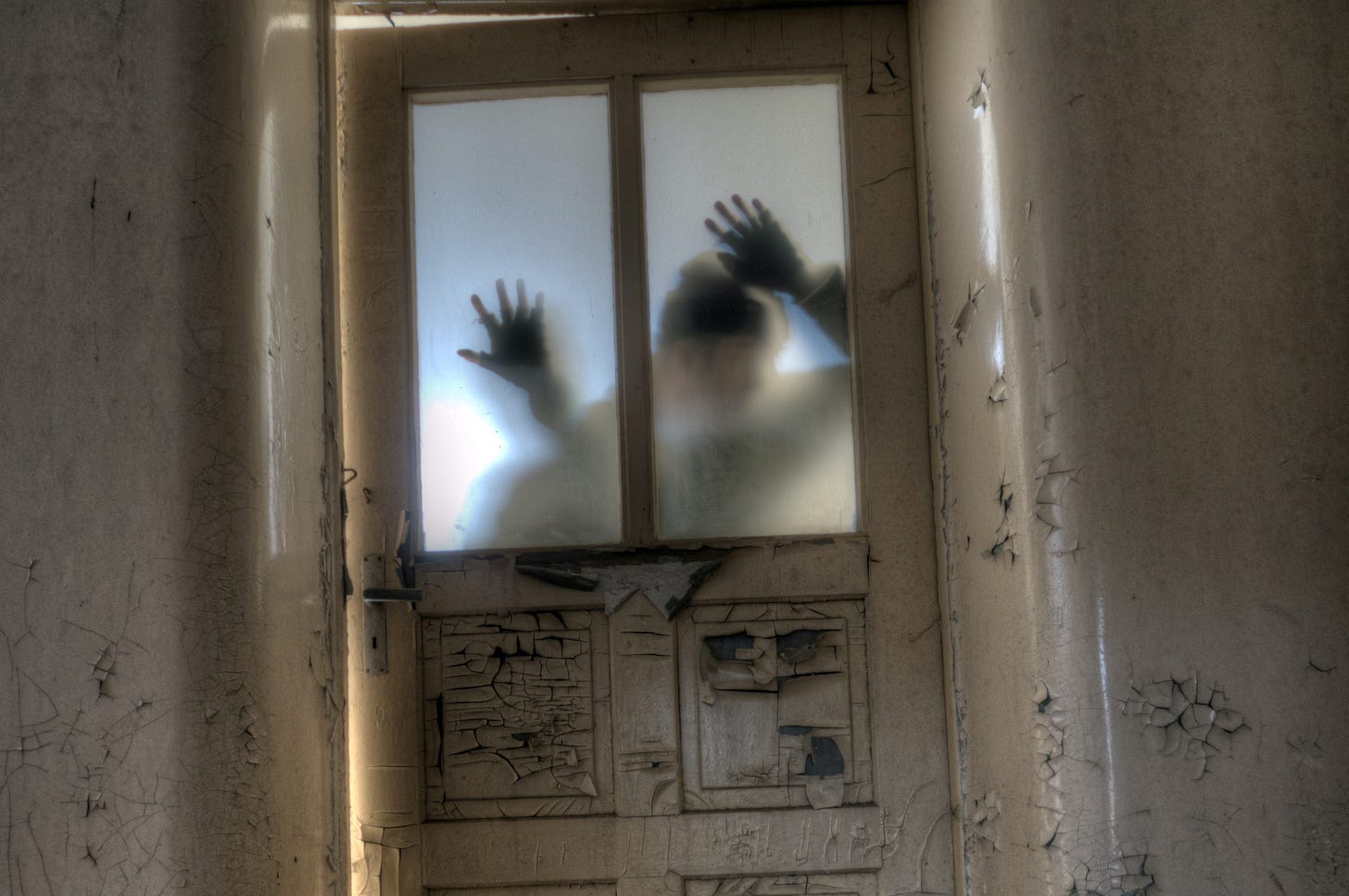

Publishing has become a zombie business, but I'm wondering if it can be brought to life in the post-pandemic era.

This post was first published with the title “Do you have a book in you?” That was unfortunate because it led some people - who obviously hadn’t read it - to send me book proposals, the last thing I was looking for that day. One person even wrote to tell me that he had three books in mind and would I like to hear about them.

We were eating dinner in Beijing one hot summer evening. My son turned to my daughter and said, "What did we ever do to deserve being encyclopedia salesmen?"

Tom was working for Berkshire Publishing then, as our China representative. Rachel had finished college early and was also working in the family business. They didn't stay. He's still in Beijing, but working in healthcare finance, and she's in her last year (in-person, hurrah!) at George Washington Law School in Washington DC.

They love books but they do not love publishing. They call it the zombie business - the walking dead.

And while I love publishing and do not intend to give it up, I have a lot of sympathy with that viewpoint. Every time I deal with one of the big old elephants in the industry, I see zombies walking.