Earth Day: The Unanswered Questions

What happens to the gas-guzzlers, diesel trains, unneeded planes, and out-of-date fridges?

I got a contract to write a book about green living when I was 29. My friends were shocked. “You don’t know anything about that,” said one.

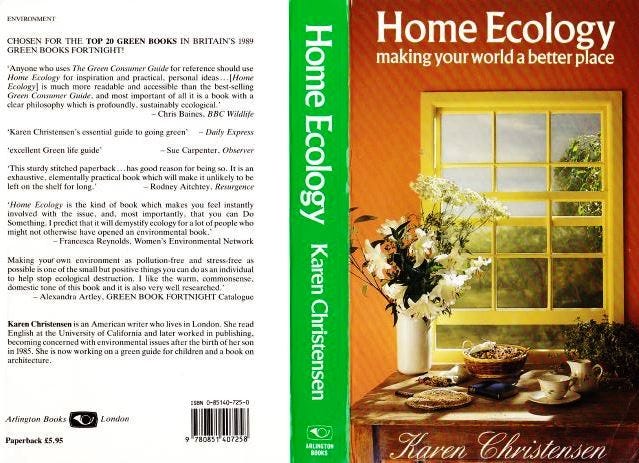

At the time, I was working for Valerie Eliot, T. S. Eliot’s widow. I took a leave of absence after we turned in a first volume of Eliot letters so I could finish what she always referred to as “your little book.”

That little book was a surprise success and I never went back to Mrs. Eliot. It was not an easy ride, though. I was threatened by the dry-cleaning and other manufacturers associations, and then by McDonalds, who were engaged in a major assault on environmentalists in the UK.

There were high points. One was an experience that authors dream of, at the annual Schumacher Lectures, named for the author of the bestselling Small is Beautiful. This was a huge event, held at a theater in Bristol, with many hundreds of attendees. Right before lunch, host Satish Kumar came on stage, waved my new book in the air, and told the audience that the author would be signing books. I guess that was my fifteen minutes of fame: I was mobbed by people who wanted my signature.

This week, I’ve participated in 12 meetings with Washington DC legislative offices, talking about passenger rail and the forthcoming infrastructure bill. Climate change and environmental justice came up frequently. We talked about electrification and reducing air pollution, and about the models provided by other countries. I wish you could hear how positive the tone is, how determined our legislators are to make big changes.

But these conversations have brought to mind a question that I’ve been asking experts for years. Everyone says it’s a great question, but no one has had an answer. Maybe you do.

My question is this: When deciding to buy an electric car (or any green replacement for existing equipment, including train carriages and locomotives), how do I factor in what will happen to my old car?

This sounds ridiculously simple. Of course the old car won’t just disappear from the planet. Someone else will drive it, using gasoline. At the end of its life, it’ll go to a junkyard. What then? How much energy will it take to process and recycle the materials and how much pollution will be created?

I asked a couple of economists the same question. They pointed out that new products are more efficient to use and often require less energy and water and fewer raw materials in their manufacture, and that the older products can be sold in the used market.

That’s true, but it wasn’t an answer to my question.

As we consider the transition to renewable energy, it is easy to focus on shiny new cars and sleek electric trains without also working out details for disposal, re-use, and re-manufacture.

For example, we’re talking about building high-speed train lines in the United States. But we also have a large network of old train lines. Some of my colleagues would like to rip them all up and replace them with electric trains. They don’t want to hear about modest upgrades that would let us get passenger service going quickly.

And no one seems to be thinking through how to divide funds between the “state of good repair” backlog and new, visionary projects.

We can “go big” with these recovery bills—that’s what I heard this week from the legislators—but there still won’t be enough money for everything we’d like to see done, especially when infrastructure has been neglected for decades. (Believe it or not, many of the tunnels, bridges, and railway lines in the United States are close to 100 years old. I’m all for making things last, but this is ridiculous.)

Here’s another question for you: Does it make sense to spend $43 billion (yes, billion) on repairs to the Northeast Corridor train line between Washington and Boston without simultaneously making some of the changes required actually to modernize, including the transition to renewable energy?

Once again, we’re focusing on the immediate action, the purchase or installation or urgent repair, and ignoring everything else. This won’t take us to a sustainable future. The concept of a circular economy and life-cycle analysis need to become part of our thinking, with tools accessible to ordinary citizens and used by policy makers.

When it comes to automobiles, my guess is that a greener option is to keep driving whatever you drive now, but drastically reduce your mileage by carpooling, walking, or riding a bike, and taking buses and trains whenever possible.

Maybe I’m wrong. But is there a way to make the calculation? Maybe it would be better to buy an electric car sooner. Or maybe we should refocus the economy on doing without private cars by making ride services and public transportation so good that that becomes possible. (How to finance it? Consider this: a study at the Harvard Kennedy School showed that in Massachusetts alone, the vehicle economy costs $64 billion a year.)

Transportation deserves the attention it’s getting now, not only because of climate change but because it has huge consequences for public health.

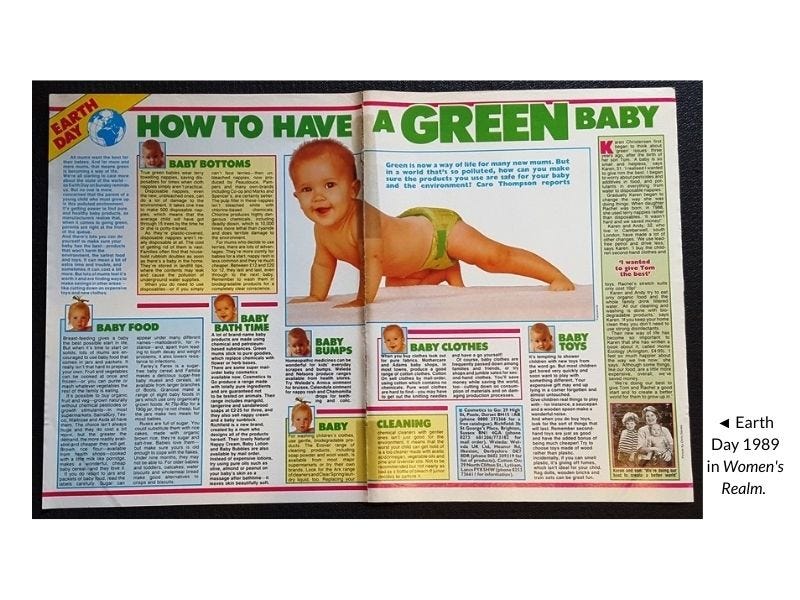

I wish I’d talked about transportation in this BBC Open Air interview. The producer really wanted to show me cycling with a baby and made me cycle up Camberwell Grove over and over to get the opening shot. (My son was amazingly tolerant!) But instead of mentioning the bike, the host refers to my not using tin cans.

We now have bike lanes everywhere, even in Great Barrington where you almost never see anyone cycling to do shopping or pick up books from the library. What we seem to have is a handful of working people who don’t have cars and then athletes in Lycra, who avoid Main Street and stick to less crowded roads.

Surely getting people onto bikes should be a priority. Instead, government spends vast sums building bike lanes and assumes they will fill up the way roads do. But just because you rode a bike as a kid doesn’t mean you can easily adapt to using a bike for shopping and commuting. We need programs to teach urban cycling techniques, road safety, and simple maintenance.

Small is Beautiful

When people ask what they can do to make a difference, I used to find myself saying, “It depends.” But there are simple principles that can be applied anywhere. My favorite is the one I think of as “small is beautiful.” Here’s what I wrote near the end of The Armchair Environmentalist, published in London in 2004:

From a biologist’s point of view, it’s not our planet that needs to be saved. The earth will take care of itself. You and I, though, the human race, we’re the ones who need saving if we want to have a place to call home.

There are many environmental problems that call for solutions beyond national boundaries, many that can only be solved as we join together in a global community determined to live together sustainably. But there are also, as you’ve seen, hundreds of small things you can do today to be part of that larger solution.

Here are four easy principles to keep in mind:

¨ Small is beautiful. Small cars, small houses, and small pets have less environmental impact, and are easier to maintain and pay for.

¨ Don’t sweat the small stuff. Do take special care over major purchases like a car or refrigerator. Don’t agonise over a plastic bag!

¨ One step at a time. Turn the thermostat down just one degree, not ten. Then another degree, and another.

¨ Be a leader. If you can afford it, be among the first to adopt new technologies like hybrid cars. This is what creates the buzz needed to take important innovations into the mainstream.

I am working on a new version of Home Ecology, for the post-pandemic era, to be published in conjunction with the new Encyclopedia of Sustainability. Your suggestions and questions are always welcome.

Happy Earth Day!

The ONE person I can think of who could have an answer is Vaclav Smil :-)

What about retrofitting these gasoline cars into electric ones? Surely there would be an industry for that. People love the design and styles of older things, if we can retrofit, there won't be as much waste involved. https://spectrum.ieee.org/cars-that-think/transportation/advanced-cars/an-electric-motor-that-works-in-any-classic-car