I was a little startled to hear from a journalist in Istanbul who wanted to talk about cemeteries. He explained that people started using the city’s cemeteries during the pandemic lockdown, and he was writing an article about their role as third places. The article, “In Istanbul, the Cemeteries Are Full of Life,” is now out and you can read it here.

First, I should clarify that he was really talking about cemeteries being used as public spaces, not third places. This is a common point of confusion. You can sometimes find a third place within much larger public spaces - a corner near a tea cart where people meet regularly, or a chess table that has become a hangout for players and spectators.

In Istanbul, the issue is a lack of green space in a city that has spectacular historic cemeteries set here and there amidst the apartment complexes and shopping streets. How natural that people should want to make use of those tree-lined avenues. As Eric Beyer writes:

By nurturing human connection, something at the core of the idea of third places, Istanbul’s cemeteries offer a compelling glimpse into how spaces designed for the dead are being used to enrich the living. Christensen notes that cemeteries have some compelling advantages, like their visual appeal and the emotions they engender, characteristics that make places like Eyüp Cemetery, one of the largest in the city, a sought-after attraction for local and international tourists alike.

Of course some people cringe at the idea that anyone would have a good time in a cemetery. I’ve never had that feeling, perhaps because the first English churchyards I visited were so beautiful and serene. They felt welcoming. It seemed natural to find a flat stone to sit on while we opened our packets of sandwiches. (In the US, the only cemetery I remember from childhood was a stark windswept hill in rural Iowa where my grandmother was buried - that wouldn’t be a place to linger.) When I made my first trip to England after the pandemic, I asked my friend Graham Fletcher to take me to pubs and country churches. It was April and the grassy churchyards were full of daffodils and primroses. It’s not all grim yew trees as you might imagine from books!

Just a few days before I talked to the Istanbul journalist, I had walked through the cemetery in Great Barrington where W E B Du Bois’s wife and children are buried (he was buried in Ghana). It’s rather bare because a tornado in 1995 took down the big trees, but it’s beautiful and spacious and has a view of East Mountain, as you can see in the photo I took only hours before getting the first email from Istanbul. But it isn’t used at all, except as a shortcut to the shopping center. We’re short of parks in Great Barrington so perhaps this is a question for the town’s cemetery commission. (That wasn’t April Fools: there really is one, and Steve Bannon is indeed a member. If you missed that story , you can find it here.)

After the interview, the subject of cemeteries seemed to be everywhere. I found a book called Churchyards of England and Wales on the sitting room table. It begins, “Churchyards, it seems to me, possess that curious quality of being at once forbidding and irresistible, so that one might at one time have hesitated to linger too long in them, for fear of being considered morbid or suspected of poetic pretensions.”

There’s Nunhead Cemetery, where my friend Richard “Bugman” Jones has led nature walks for many years. It is one of the seven grand cemeteries that ring London, and known not only for its Victorian tombs but as an urban wild space to be preserved and protected. (Picnics are, apparently, not allowed.)

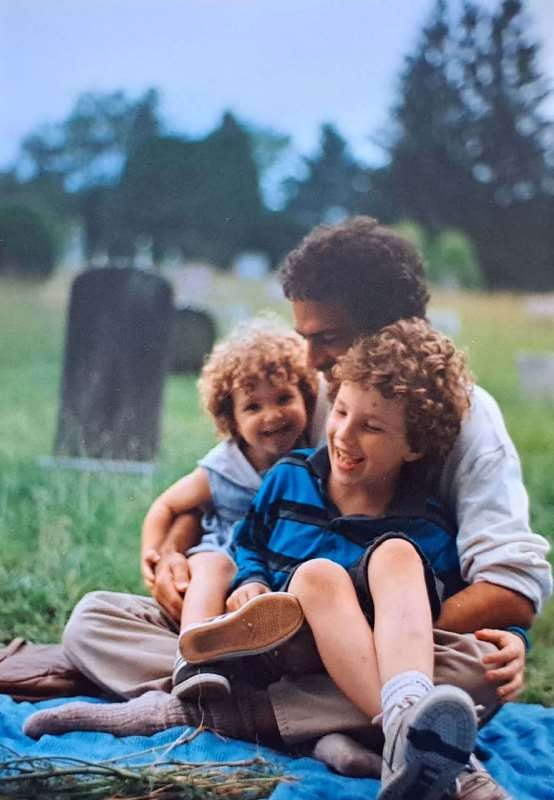

I even found some old notes about cemeteries that reminded me of a picnic with friends in upstate New York. My children grew up thinking that cemeteries were pleasant places - the only rule being not to walk across a grave.

A third place is where people meet, and talk, regularly. A cemetery, whether you believe in an afterlife or not, offers something rather different. It provides a sense of connection with the people who’ve gone before us, women and men who have walked the same paths and looked up at the same hills, and faced many of the same challenges as we do. (And I’m always reminded how much easier and safer our lives are. Graveyards are a good reminder to be grateful.) In China, Qing Ming is “Tomb Sweeping Day,” a significant holiday on which one remembers one’s ancestors. I have never visited the grave of any of my own ancestors, but I have often traced lettering on a time-roughened tombstone and tried to picture the young mother whose life is summed up in a line or two.

The essence of a third place is that it makes you feel connected and confirms that you have things in common with people who aren’t just like you. This is balm for loneliness, a source of comfort in difficult times. In that sense cemeteries might be, for all of us everywhere, a kind of public space to cherish and cultivate.

A shout-out to the Massachusetts Cultural Council, which has given me a $5,000 grant to help with the book, which is coming on next February. As a friend pointed out, that’ll give me time to make some final corrections after the US election, and after the after. The word “havens” certainly applies to cemeteries, but I’m not sure “hangouts” will ever be a good fit.

Nice piece. I love running in cemeteries. They make for great courses, some with inclines and loops and dips that offer a great challenge. Older cemeteries in particular have these features. Plus you’re never at a loss for company.

Love this article. Green-Wood in Brooklyn is hands-down one of my favorite “parks” in NYC.

Congrats on the MCC grant!