Great Barrington at the Supreme Court?

And wondering what W E B Du Bois would write about today's issues

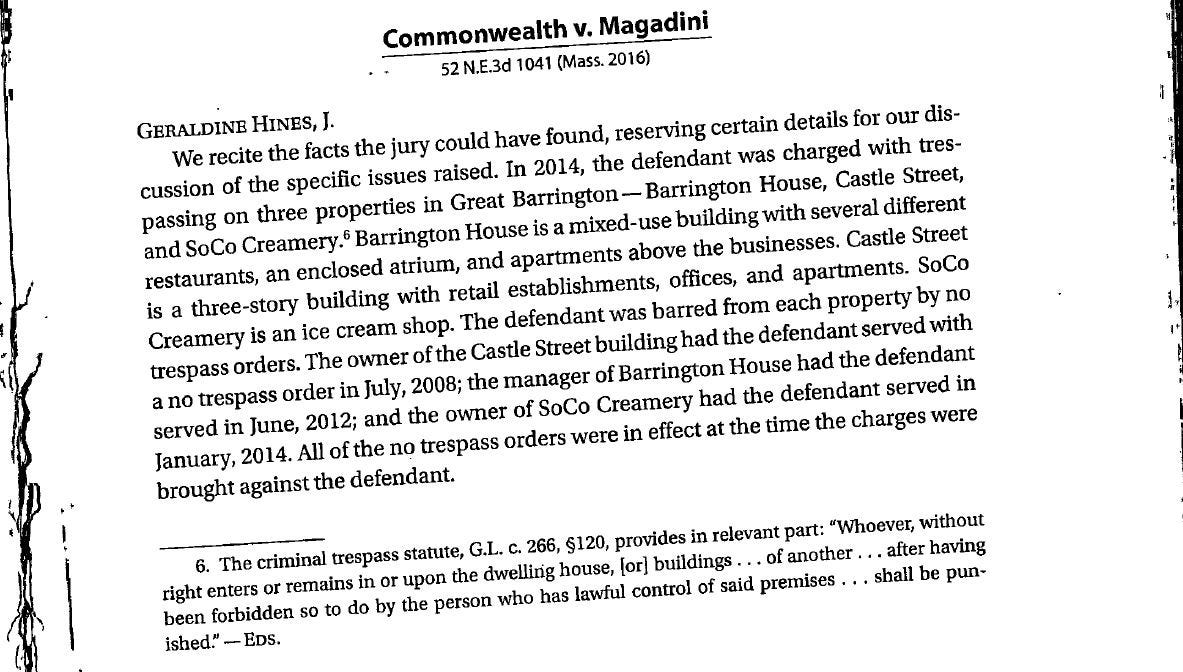

When my daughter opened her property law textbook a couple years ago, she was startled to find a case from her tiny hometown - “Commonwealth v. Magadini - 474 Mass. 593, 52 N.E.3d 1041 (2016)” - set out in detail. This week, the US Supreme Court has been hearing a case about the “camping” rights of homeless (or unhoused) people and I wouldn’t be surprised if the “Commonwealth v. Magadini” is mentioned.

One of the spots where Mr Magadini lived for a while was the town gazebo, the bandstand behind Town Hall that you can see in the photo I took today. (This Town Hall is where W E B Du Bois wrote that he learned about democracy.)

The legal issues went on for years, amply documented in the online Berkshire Edge. While all that happened some years after Berkshire Publishing released the Homelessness Handbook, the book does lead with a story by one of our staffers and set in one of the buildings where David Magadini later camped:

In the midst of work on the Homelessness Handbook, I took a break to browse through the thrift shop below our offices in Great Barrington [at 4 Castle Street]. Coming in at the same time was a man with a large backpack and a pile of bedding, in the market for a warm sleeping bag. He appeared to be a person living on the road if not the streets. I had read often enough about how homeless people are often treated as if they are invisible, so I made an effort to be friendly. We chatted a bit about his travels, and I told him my name was Marcy Ross. I was unprepared, though, for his invitation to buy me lunch. I’d already eaten so I declined, wished him a good trip on the road, and beat a hasty retreat.

Back in the office, I told David Levinson the story. He wondered why I didn’t just go for a cup of coffee with the visitor. I wondered myself. Did I fear the judgments of the ladies who ran the thrift shop? What other people might think? I couldn’t help but remember a quote we cite in the Homelessness Handbook, “The vagabond, when rich, is called a tourist.” Great Barrington is filled with tourists; I wish I had seen this visitor as just another one of them.

The many biblical injunctions quoted in these pages are reminders that it has never been easy or natural to see the poor and the homeless as ourselves—but we should never stop trying to do so.

By chance, I’ve had a compositor preparing an ebook version of Berkshire’s Homelessness Handbook. It’s been used in classes, but was never turned into an ebook because the pages were so full of quotations and sidebars and illustrations. I had to decide how to adapt it, which turned out to be fascinating because it has so much history and philosophy, along with the more obvious sociological discussion.

Mr Magadini was jailed for a time, ran for Town Moderator, and became quite a local figure.

The case before the Supreme Court relates to the encampments that have become common in big cities, a completely different situation from our lone, local eccentric. Nonetheless, human displacement is going to become more common and complicated in the years ahead. This is yet another situation in which we need to stop thinking about people as “other,” somehow less than human, and to find ways to live together in peace. I’m happy to think that the Homelessness Handbook might make a contribution to that.

Here’s a sidebar from the book, which I picked before seeing that it mentions Columbia University, which is also in the headlines this week:

Postmodern fiction is particularly well suited to the theme of homelessness due to the contemporary preoccupation with silences, gaps, displacement, alienation, and paradox. Homeless metaphors are often a means to represent the “uncanny” (the German word unhiemlich literally means “un-home”) to hypothesize an ontological homelessness or a fragmented subjectivity, or to explore nonlinear narrative. Images of homelessness are found in Don DeLillo’s Underworld (1997) and Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), and displacement is a recurring theme in texts by Cormack McCarthy, Toni Morrison, and Paul Auster.

In Paul Auster’s Moon Palace (1989), the protagonist is a Columbia University student who runs out of money and ends up living rough in Central Park. His homelessness is a portal into a narrative that meditates on the American journey “west” and the myth of the frontier. In Timbuktu (1999), Auster returns to the theme of homelessness in more detail. The narrator of Timbuktu is Mr. Bones, the pet dog of a homeless man named Willy Christmas. The text represents displacement in a unique way, exploring three versions of America: one through the eyes of a homeless man with mental illness, another through the life of an immigrant urban boy, and the last through the narrative of a family living in the comforts of suburbia. While Willy may be homeless, Mr. Bones does not become “homeless” himself until Willy dies on the street. Therefore, the experience of homelessness—and its associated fears, trials, and loneliness—is introduced to the reader by the homeless dog, not the homeless man.

—Amanda F. Grzyb

“If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich.” —John F. Kennedy

Hi Karen. I’m retired now but I wrote the Magadini decision when I was on the SJC. Students at BC Law, where I teach, study this case as well. I came across your post as I was preparing to speak to our law students about this case in the wake of SCOTUS’ Grants Pass decision. What a time we live in.