Guardians of the flame

Listen to "A Life in Biography"

The neighborhood leaf blowers held off on Sunday morning for long enough to let me join Carl Rollyson on his podcast, “A Life in Biography,” to talk about Writing Great Tom: T. S. Eliot and the Keepers of the Flame.

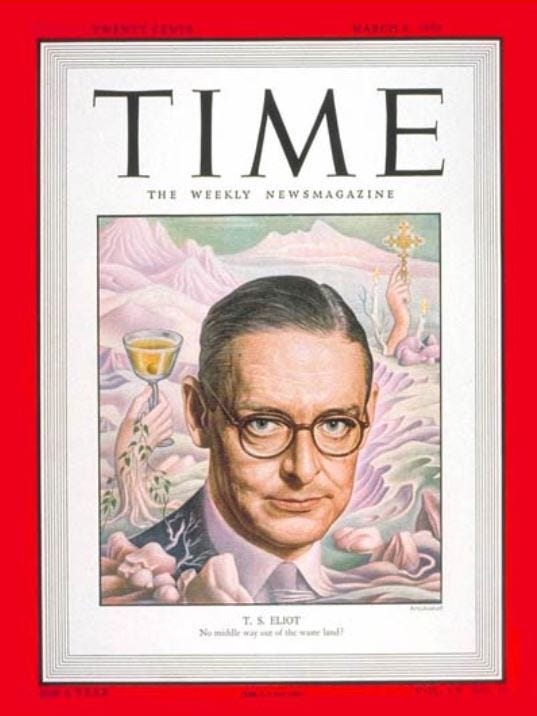

The author, T. S. Matthews, had put Eliot on the cover of TIME Magazine in 1950 (Matthews was then the editor). That was 2 years after Eliot won the Nobel Prize in Literature. It was 2 decades later, and 5 years after Eliot’s death, when Matthews was commissioned to write a biography of the man he had so admired. Matthews didn’t think he could gather enough information to write the book Harper & Row had commissioned, but he thought he might turn the story of trying to write it into a book - a detective story, of sorts.

Carl and I also talked on the podcast about the biography I’m writing now, about Valerie Eliot (Eliot’s second wife, widow, and guardian of the flame), who makes frequent appearances in Writing Great Tom. (She is not one of the heroes of that story.)

As I told Carl, I’m a reluctant biographer. My situation is the reverse of Matthews’ - he was struggling to get enough information - though I have faced exactly the same problems with major libraries that he details in Writing Great Tom. But I just couldn’t get excited about writing a full life story about a woman who had alternately charmed and frustrated me when I was young, even though I’d amassed vast amounts of material about her that no one else has.

But I finally saw that her story is a fascinating example of a woman’s pursuit of power through marriage. She paid a heavy price, trapped in the role she’d had to play to win her elder Great Man. No one else has ever taken a serious look at her, even though she’s the one who came up with the idea for “Memory",” Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “million-dollar song,” made famous by both Cats and Barbra Streisand, and it was her wealth that saved the major British publishing firm Faber & Faber in 1990.

This passage from Robert Caro’s Working is what I keep in front of me:

While I was researching The Power Broker, and learning more and more about Robert Moses' amassing of political power and use of political power, I came to feel more and more strongly what I had felt when I first conceived of the book: that if (and this was a big "if" with me) I could just write it well enough, tell the story of his life the way it should be told, that story would cast light on the realities of urban political power, power in cites, power not just in New York but in all the cities of America in the middle of the twentieth century. And when I finished that book, I knew the one I would like to do next: a book about national political power. And I felt that I had learned that if you chose the right man, you could show quite a bit about power through the life of that man. But you have to choose the right man. How do you do that? I spent a lot of time trying to figure that out. I came to feel that one way was to find someone who had done something no one had done before, as Robert Moses, in a democracy in which political power supposedly comes from being elected, had, without ever being elected to anything, amassed an unprecedented amount of power—far more power, in fact, than any city or state official who had been elected—had held that power for more than four decades, and with it had done so much to shape a great city in the image he wanted. If you choose that man, the man who did something no one else had done, and can figure out how he did it, you get insights into the essence of power.

Speaking of Robert Caro, here’s a flashback to 2020. See the red arrow, bottom left, in the photo below “‘The Power Broker,’ a biography by Robert Caro, has become a must-have prop for numerous politicians and reporters appearing on camera from home,” said the New York Times. It’s a fascinating book, as is Working, with a great deal about community cohesion and the impact of infrastructure decisions. I read it years ago because Robert Moses and Lewis Mumford had been sworn enemies, and during the pandemic I bought a secondhand copy and included in a care package sent to my son in Beijing, telling him he should have it on display there.