I’ve been ill and I’ve been feeling guilty.

A few weeks ago I hosted an event for the Train Campaign, and per state protocol no masks were required. We were in a big room at the historic railroad station in Canaan, Connecticut. Speakers included two politicians and author Simon Winchester (event video here), and the room was full, about 50 people. Lots of close contact, and afterwards some of us went downstairs to the brewery to continue the conversation.

It was wonderful to see people and to sit and talk over a beer, but a few days later, it felt exhausting to walk up the hill to Tanglewood. After another three days, it occurred to me that fatigue, chills, and loss of appetite might mean I was ill. Indeed, my temperature was 102.5F (39.2C).

I was in bed for over a week. A COVID-19 test was negative, and I have no idea what exactly what bug I picked up. I was awfully glad, however, to know that I’d had my two Pfizer vaccine shots.

But I also appreciate my body’s response. Fevers are generally beneficial, part of a healthy defense system.

I was an antivaxxer

The title of this letter is accurate. I was once an antivaxxer (though in those days, in England, the term was not vaccination but immunization).

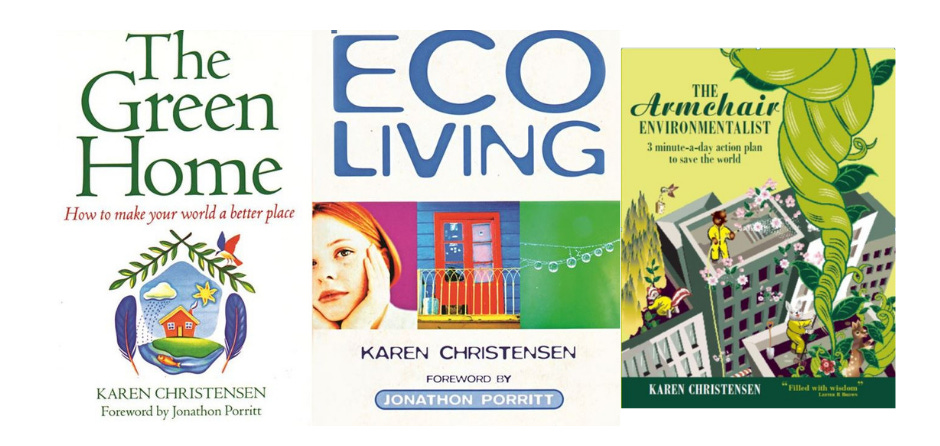

Here’s how it happened. When I was 29 and working for T. S. Eliot’s widow Valerie, I got a contract to write a book about green living, or what I called “home ecology.” In the chapter on children, I quoted a number of critics of immunization. The same text went into a US edition the following year, and in later versions from Piatkus Books. Here are a few paragraphs that I wrote in 1988 and edited a bit in 1995:

Most health care professionals insist that universal immunisation is both safe and necessary. They tell parents, for example, that there's a clear choice between having measles and having a vaccine. It may therefore surprise you to learn that a 1978 survey found that more than half the children who contracted measles had been vaccinated against it, and a study at the Primal Health Research Centre in the UK, lead by Michel Odent, found that there was five times the incidence of asthma, a modern plague amongst schoolchildren, in children who had received the whooping cough vaccine. Vaccines are intended to work on the body's immunological system and it is not surprising there could be side effects like this. . . .

A common justification for universal vaccination is that they are largely responsible for this century's reduction in infant mortality. The common childhood diseases were, however, in decline before many modern vaccines came on the scene. Better hygiene, clean water and an improved diet were crucial factors.

If you have a young baby, take the time to look into this question before you make up your mind. Your clinic (or GP or health visitor) will press you to have the baby's first set of shots at two months, but the timing is not crucial - they like to start at this age because you are still bringing the child into the clinic regularly.

The possible risks with the whooping cough vaccine have got a great deal of attention, but there are concerns about other routine vaccinations. One might think that a sickly infant would need immunisation more than a robust child, but children who are already unwell are most vulnerable to ill-effects from vaccination. An American study shows a connection between the DPT vaccine and cot death - the most likely explanation being that in these cases the vaccine was the last straw for a child whose system was already under stress.

My reservations about immunization were consistent with my thinking about healthy living and my reservations about an autocratic medical establishment.

To be honest I hadn’t thought about the medical establishment before I got pregnant because I’d never been ill.

Being pregnant didn’t make me ill, either. I was 27, strong and fit. I cycled to work until 2 days past my due date. But the medics wanted to take charge, to test and monitor and control. The nurse at the local surgery used to greet me with, “Still disgustingly healthy, aren’t we?”

Both my children were born at home. This was possible under the UK’s National Health Service, though the doctors argued with me about it all the way through. The first birth went smoothly, but the NHS midwife made a serious, and dangerous, mistake afterwards simply because she was following procedures and not paying attention to what was actually happening.

When my daughter was born three years later, I had an independent midwife. The whole thing was a piece of cake because she knew how to read a woman’s body in labor. Her medical training didn’t override her observations and good sense.

This contributed to my reluctance about immunization, especially for infants. Babies develop strong immune systems under the right conditions: being breastfed is important, as is being exposed to a reasonable amount of dirt and bacteria. (Some vulnerable children today are suffering from respiratory problems because the lockdown meant they didn’t get routine exposure that builds natural immunity. Here’s one article on subject.)

I was also disturbed by the way doctors tried to scare me about home birth even though statistically home birth was a safer option. If you check out statistics on home birth and especially on caesarean section deliveries in the United States, it’ll give you a healthy skepticism about the medical-industrial complex.

So, you see, I have a certain caution about medical advice and some sympathy with the idea that healthy human bodies can develop natural immunity and that society can develop herd immunity, too.

But COVID-19 is different, and so are a handful of other serious diseases (including measles) that we vaccinate against. COVID-19 and whatever other coronaviruses lie in our future are new, volatile, and dangerous not only to individuals but to the functioning of our societies. The collective impact matters. It appalls me that right-wing antivaxxers (including my brother) would put other people (like my mother, for example, whose 87th birthday is today) in harm’s way.

My children, incidentally, are firm believers in medical science and will probably be horrified if they read this. By the time they were in elementary school, they were getting all the routine vaccines. We’ll see what they decide about infant vaccination when they have children!

Back to Home Ecology

I was eager to get the Pfizer vaccine and remain impressed by the speed of vaccine development. I worry, though, that we might get the idea that there is a similarly quick fix for every problem. There is no vaccine that will reduce greenhouse gas emissions and stop climate change. That comes down to us, and to the leaders we elect, the companies we buy from, the organizations we support.

Post-pandemic behavior makes it clear that most of us want to go back to familiar patterns, and to stop worrying about consequences of our everyday behavior. I was well aware of that by the time I finished my first book manuscript, because even the friend who had inspired me to think about home ecology really did not like the idea of a book on the subject. She worried that I would make her feel guilty about the things she wasn’t doing.

Jonathon Porritt, a renowned British environmentalist, wrote a foreword to the second edition and specifically praised the book for not make people feel guilty. It’s a little ironic that it now makes me feel guilty!

I feel guilty because I haven’t done enough, and haven’t found new ways to put practical information into people’s hands. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report that came out last week, along with a year of extreme weather, has made me see that I have to make “home ecology” a consistent part of everything I write and publish. But I don’t want to make you feel guilty or besieged, either, so I am making Home Ecology (the title of my first book, which I’ve circled back to) a separate newsletter that you can sign up for. Here’s a link to the first post, about staying cool during a heat wave without adding to the problem of carbon emissions.

In it, I’ll be using material from my previous books as well as plenty of new information, and links to the best of what’s being written today. I will doubtless make fun of some of the ideas experts come up with. And I’ll keep in mind that people have limited time and limited money. We need to know what we can do that will have the most impact.

A symbol of enlightenment and rebirth

The British designer William Morris is known for saying, “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.” I decided to try to grow Chinese lotuses this year since I can’t go to China, and they turn out to be both beautiful and useful. Not only are the flowers glorious, but they will produce edible seed pods, edible roots, and I’ve learned that I can even use the leaves to make certain steamed rice dishes.