Reading W. E. B. Du Bois in Great Barrington (free ebook)

Juneteenth: A day, a time, a moment to remember

I’m having a little trouble getting my tongue around the word Juneteenth, but it’s good to know that it’ll be easy and obvious to future generations. I can’t help thinking about all those who worked to end slavery, and those who have worked for too long since then to bring fitting recognition to that momentous event.

Americans are divided about many things, but the unanimous vote to commemorate the end of slavery has to be a highlight of this period of US history.

I’ll be able to celebrate it with my mother and my twin brother and his African American twin sons because I’m making my first post-pandemic flight on Juneteenth. This will be the first time I’ll meet the boys. All of us twins share a September birthday, so I think that’ll merit some celebration, too.

Berkshire Publishing’s focus has always been the world, not just the United States. Everything we’ve published on Black history or culture has been in a global context, except for a short book with a ridiculously long title, The African American Community in Rural New England: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Clinton A. M. E. Zion Church. I’m making copies of the ebook free for the Juneteenth weekend, details below.

The book is a local history, inspired by the fact that a great Black American historian and activist, W. E. B. Du Bois, grew up here in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. It tells the story of a small church, center of the Black community of the time, and contains a good deal written by Du Bois himself as a teenager.

The church is today being restored as a educational center and we’ve been pleased to donate many copies of the book to be used for their fundraising efforts. (Read more about this project at Clinton Church Restoration.)

If you would like a free ebook, you can get it at our website, as a PDF, by clicking here. If you prefer an ePub ebook, email me (just reply to this email and it’ll get to me) and we’ll get one sent to you as a freebie via eBooks.com, where it is for sale throughout the world.

And if you’re like me and just want to read a little bit about Du Bois, here are a few passages:

The Negro church of to-day is the social center of Negro life in the United States, and the most characteristic expression of African character. . . . Thus one can see in the Negro church to-day, reproduced in microcosm, all the great world from which the Negro is cut off by color-prejudice and social condition. (W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk,1903).

Despite its small size, the Black population was not a homogeneous mass. Du Bois again provides the details:

My family was among the oldest inhabitants in the valley. The family had spread slowly through the county intermarrying among cousins and other black folk, with some, but limited infiltration of white blood. Other dark families had come in and there was intermingling with local Indians. In one or two cases there were groups of apparently later black immigrants from Africa, near Sheffield, for instance. Surviving also was an isolated group of black folk whose origin was obscure. We knew little of them but felt above them because of our education and economic status. (Du Bois 1968, 83)

Joining these groups were the newcomers who came from the South and from northern cities such as New York and settled in Great Barrington beginning in the late 1860s. Some were former slaves or children of slaves, and others were employees or former employees of white families in the North. They were but a few dozen in the massive migration of Blacks to the North in the middle years of the nineteenth century, but several of these men and women took a central role in the founding of the Clinton A. M. E. Zion Church.

In his columns in the Black newspaper the New York Globe (later called the New York Freeman and, later still, the New York Age) from April 1883 to May 1885, Du Bois mentions many members of the Great Barrington community. . . .

What was life like for these folks of Great Barrington? What we know comes mainly from the writings of W. E. B. Du Bois. He devotes many pages of his autobiographies to his boyhood and adolescent years; of even more historical importance are the dispatches he wrote on the Great Barrington community for the New York Globe. . . .

Du Bois described his childhood in Great Barrington as “a boy’s paradise,” but he also learned about distinctions based on wealth and social class, and he experienced the “veil,” or the “color line,” that separated Blacks from whites. That experience spurred him in his lifelong effort to pull down that veil and erase the color line. Despite the separation and discrimination, Great Barrington’s Black community went back several generations, and many of the people had lived their entire lives in town. And, while poorer than most whites and excluded from some activities (such as employment in the mills or by town government), Blacks clearly saw themselves as part of the community and had a place in it. This perception was based on the day-to-day reality of life in Great Barrington. If they so desired, they could send their children to the public schools that were formed in the 1860s, and a few children also attended white academies. They voted and attended the annual town meeting (but were not active politically in other ways), owned property, and shopped with their white neighbors in the stores on Main and Railroad streets. . . .

In an interesting historical note, Du Bois himself (at the age of fifteen) was elected temporary secretary of the Sewing Society on 19 December 1883, when temporary officers were needed for the hour or two between the termination of the existing board and the election of the new board. His biographer, David Levering Lewis, suggests that Du Bois’s involvement with the Sewing Society was the beginning of a lifelong pattern of his working closely with women.

The Sewing Society suppers were open to the entire community and were held in members’ homes; over the years in the homes of Jason Cooley, Lucinda Gardner, Mrs. J. Moore, William Crosley, Mrs. M. Van Allen, Manuel Mason, and Jefferson McKinley. The suppers often included entertainment (as did weekly meetings, on occasion) and raised money for the church, whose major expense was paying the visiting pastors. Du Bois reported that the entertainment varied:

They were entertained at their last meeting by speaking by the children. And Mr. Egbert Lee related some interesting stories of his experience in the late war.

After the supper there will be a debate on the following question: “Ought the Indian to have been driven out of America?” Messrs. Crosley and Du Bois will take part in the discussion. . . . The debate which I spoke of in my last letter took place last Wednesday evening at the house of Mr. William Crosly [sic]. It was contested warmly on both sides and strong arguments were brought up. It was finally decided in favor of the affirmative.

The last monthly supper of the Zion Sewing Society, at Mrs. L. Gardner’s, passed off enjoyably and the company was entertained by Mr. Fred Sumea, who plays finely upon the accordion, and by a debate between Messrs. Mason and Chinn on the well-worn question: “Which is the more destructive, Fire or Water?” Mr. Chinn on the side of Fire was decided victor.

In May 1883 the Sewing Society formed a Literary Society. As Elizabeth McHenry has recently pointed out in her book on African American literary societies, Forgotten Readers, literary societies were a significant component of Black life beginning in the early nineteenth century and continuing well into the twentieth century. As elsewhere, the formation of the Literary Society by the small Black community in Great Barrington shows clearly the importance these individuals placed on reading and learning and the discussion of ideas. Well into the next century the society and other church groups remained active, organizing public readings, plays, musicals, debates, concerts, and guest speakers (including Du Bois himself). Most of these events were public ones, staged in larger venues than that of the church, such as the second-floor meeting room of the town hall (at the time the whole second floor was open for meetings), and the paying public helped support the church.

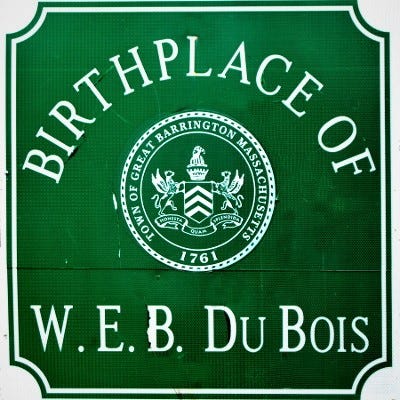

The conflicts over putting up signs about Great Barrington’s being Du Bois’s birthplace and then about naming a new school for him took place not long ago (read about them here). But I received my COVID-19 vaccine at the W. E. B. Du Bois Middle School, Black Lives Matters signs are still evident all over town, and now we’re celebrating Juneteenth. It’s a beautiful day.

Happy Juneteenth!

PS: There were a lot of comments on my post about resigning from Penn Press, and I’ve added an update, too, on the webpage. You can read the comments here.