Songs for the people - celebrating Black History Month

Voices from the 19th century speak to us today in Invisible Poets

I was reading on the sofa at a friend’s house in Washington DC and glanced up at the bookcase. The title Invisible Poets leaped out, especially when I noticed that the author’s name was the same as my friend’s. It turned out that her mother had been an English professor, who had specialized in 19th-century Black literature.

How frustrating to think that I’d met Professor Sherman several times and never had a chance to talk about her work. I’m now republishing Invisible Poets: Afro-Americans of the Nineteenth Century with a foreword by Jaki Shelton Green, poet laureate of North Carolina, who knew the book well and had been inspired by it.

The following extracts come from an article in a Rutgers University publication. The writing of the book, as well as the writing of the poems themselves, is something to celebrate.

“Afro-Americans of the 19th century are invisible poets of our national literature… their achievements, impressive both in quantity and quality, remain unacknowledged,” she said. Unlike Angelou their voices have long been silenced and generations of Americans, black and white, know little of their lives and work, she added.

“My writers were not in anybody’s books,” she said. “I went page by page through 19th century newspapers and rare volumes to find the poems.” Collecting biographical data required writing letters all over the country and tracking down living relatives.

“George Moses Horton, who could not read or write, dictated his poems for a volume in 1829 and later published two more volumes of poetry while still a slave. “Joshua Simpson, who had only three months of schooling, published more than 50 poems in 1874.”

“No group of writers in any place or time has struggled [so] to surmount lowly birth, poverty, lack of education and life-long discrimination to produce a body of literature.”

The poet hath a realm within, and throne, And in this soul singeth his lament, A Comer often in the world unknow— A flaming minister to mortals sent; In an apocalypse of sentiment He shows in colors true the right or wrong, And lights the soul of virtue with content; Oh! could the world without him please us long? What truth is there that lives and does not live in song?

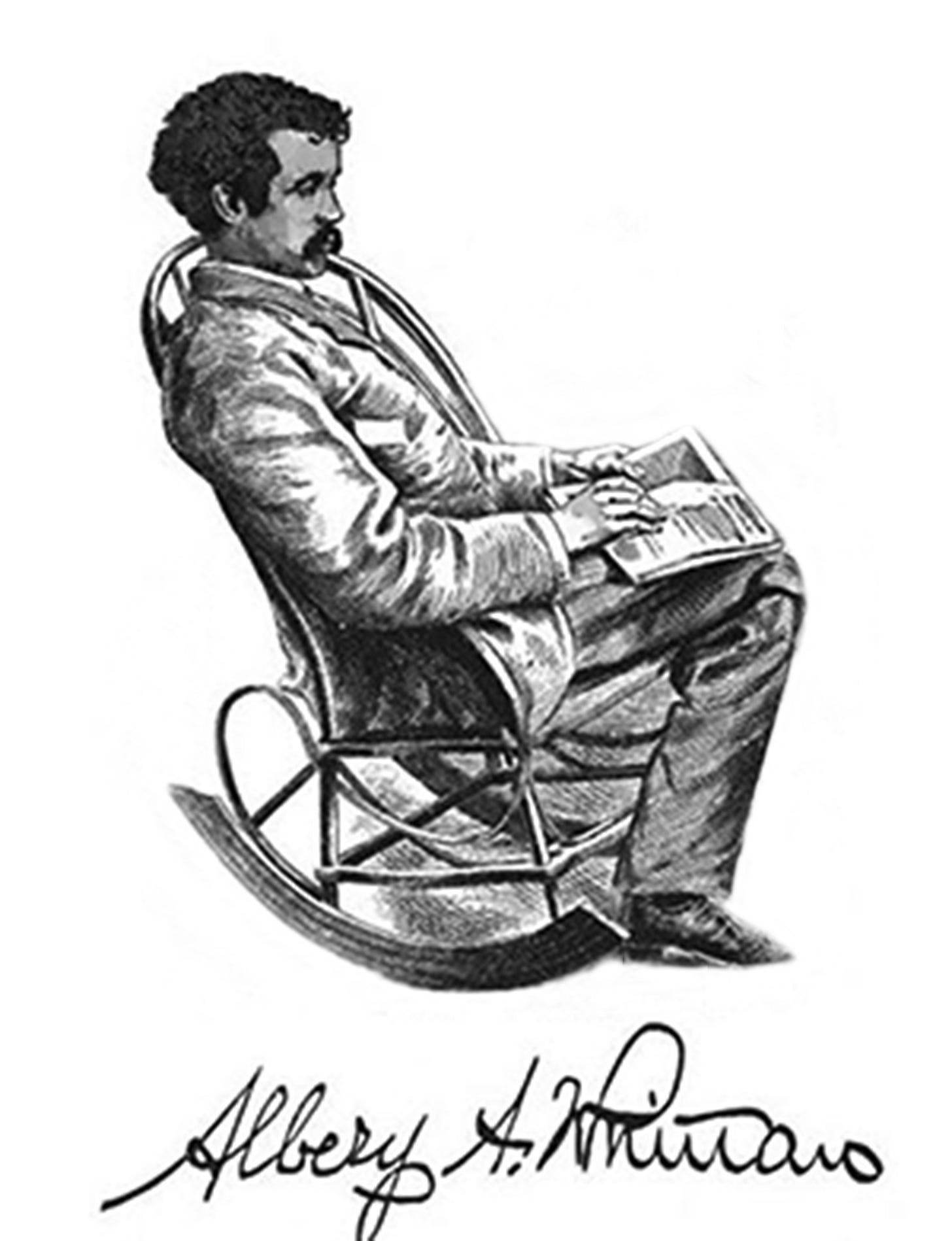

So wrote Albery Allson Whitman in 1884. Born a slave and with only a year of formal schooling, Whitman published seven volumes of poetry and rose to be his century’s “Poet Laureate of the Negro Race”.

George Moses Horton could not read or write when in 1829 he dictated the 21 poems that were published as The Hope of Liberty. This “Colored Bard of North Carolina,” the first black man to publish a book in the South, then wrote another 150 poems for two later volume. Horton spent 68 years in slavery, but his poet’s voice freely sand the beauties of nature, dreams of love, and hope of liberty.

Must I dwell in Slavery’s night, And all pleasure take its flight, Far beyond my feeble sight, Forever? Something still my heart surveys, Groping through this dreary maze; Is it Hope? – then burn and blaze Forever? The power of poetry flows, like a river, to all- “Women, children, men” Come, Clad in peace, and I will sing the songs The Creator gave to me when I and the Tree and the rock were one.

An ancestor of this sentiment is Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, the most successful African-American poet of her age, who devoted her life to abolitionism, race advancement and equality, women’s and children’s right, Christian morality and temperance. In addition to her essays, speeches and fiction, Harper’s 120 poems remain an invaluable legacy.

Let me make the songs for the people, Songs for the old and young; Song to stir like a battle-cry Wherever they are sung.

Harper’s songs were to “thrill the hearts of men/With more abundant life”, they were songs for “the weary,” for “little children,” for the “poor and aged,” songs needed by the world.

Our world, so worn and weary, Needs music, pure and strong, To hush the jangle and discords Of sorrow, pain, and wrong. Music to soothe all its sorrow, Till war and crime shall cease; And the hearts of men grown tender Girdle the world with peace.

Embracing all and looking upward into the bright new day, “On the Pulse of Morning” offers a positive challenge for today:

Lift up your hearts Each new hour holds new chances For a new beginning Do not be wedded forever To fear, yoked eternally To brutishness …. Here, on the pulse of this fine day You may have the courage To look up and out and upon me, the Rock, the River, the Tree, your country ….

Mrs. Harper also gathered, by name, people of all religions, races, and countries into the one world of a poem and urged them to renew their lives and their earth.

To plant the roots of coming years, In mercy, love and truth; And bid our weary, saddened earth Again renew her youth …. Oh! earnest hearts! toil on in hope, ‘Till darkness shrinks from light; To fill the earth with peace and joy, Let youth and age unite; …. The age to brighten every path By sin and sorrow trod; For loving hearts to usher in The commonwealth of God.

Although the 19th century brought much disappointment and despair along with triumphs to African-Americans, black poets continued to hymn the rebirth of age-old dreams and, with hope, to say “Good morning” to the coming new day.

“Sherman’s work of literary resurrection is a signal achievement, combining deft historical detective work with a subtle critical sensibility.” — Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Research Institute at Harvard

The new edition of Invisible Poets will be available in June, in hardcover, paperback, and of course ebook.

I didn't realize that T S Eliot was described as the "invisible poet" https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/a/hugh-kenner-9/the-invisible-poet-ts-eliot/. And by Hugh Kenner, no less. This feels fortuitous, because Kenner was one reason I applied to UCSB. The other was Marvin Mudrick, who had me teach a class on literary letters just a couple years before I happened to get a job working on the T S Eliot letters. All a bit too circular!