T S Eliot: Never & Always

I can't get away from the Eliot story, no matter how I try.

I won’t be able to go to China for a while so it is a special pleasure to be appear in the Shanghai Review of Books, a major Chinese literary journal, thanks to Qiu Xiaolong. We have never met but our common interests include T. S. Eliot, who even figured in one of Qiu’s detective novels. He proposed that he interview me about Valerie Eliot, Eliot’s second wife, as a lead-in to the centenary of Eliot’s most famous work, The Waste Land, in 2022.

You can read the interview here in Chinese, or in Google Translate’s English version. (We’re hoping to publish it in an English-language journal, too, adapted for a US or UK audience.) If the English link doesn’t work (it depends on browser settings, I think), drop me a line if you’d like a copy in English.

The interview is really a conversation, as Xiaolong knows more than I about Eliot’s poetry and its popularity in China. Here’s a little bit of it:

QIU Xiaolong: The interest in Eliot has never waned among Chinese readers. As early as the thirties of the last century, the well-known translator Zhao Luorui published the first Chinese translation of The Waste Land, and just recently, there's a Chinese translation of Eliot's biography T.S. Eliot: An Imperfect Life by Lyndall Gordon. . . . [T]he Chinese translation . . . was named as one of best books for the year, which in itself speaks of Eliot’s popularity among Chinese readers. In this biography as well as in some others, however, there seem to be a popular tendency to present Eliot as an exploiter—though probably not in common sense of the word—of the women in his life. For instance, some lines in The Waste Land are supposedly said by Vivien: My nerves are bad to-night. Yes, bad. Stay with me. / Speak to me. Why do you never speak? Speak./ What are you thinking of? What thinking? What? /I never know what you are thinking. Think. That might have come from Vivien, but it’s way too much to claim that Eliot exploited her. As it seems to me, a poet's achievement lies in rendering the personal into the impersonal. What do you think?

Karen CHRISTENSEN: I prefer to think of what the poet does as rendering the personal into the universal, speaking to all of us, finding common meaning and feeling. Is that impersonal? I know that Eliot did not want a biography written, and I can sympathize with that. He burned many letters, too, feeling that it was his life, not something that belonged to future scholars and writers. (Valerie would no doubt feel the same about being written about.) But we humans look to other lives for understanding, and we’re curious about other people. I think it’s no wonder that we are now so curious about the women in Eliot’s life. For an austere man who took a vow of celibacy when he separated from Vivien, it’s quite intriguing that there were so many women. There are four who are now getting attention, and there were others who loved him and at least one asked him to marry her.

When I was working with Valerie, I spent a lot of time with the letters from the 1920s, and I got to know Vivien Eliot quite well, in a way, from all those hours transcribing her handwritten letters. She was a troubled, erratic, ambitious woman, and Eliot obviously thought her judgment of his poetry was significant. And she contributed to it in various ways: certainly with her vivid voice, her way of looking at the world, but also in her edits to The Waste Land. I was looking at the copy of the Facsimile that Valerie gave me on my first day working for her (I am sure she was very proud of it). I didn’t notice then that while she indicated Vivien’s edits, she, nor Fabers, credited Vivien: only Ezra Pound. I think today in a similar publication, Vivien would be more clearly acknowledged.

In fact, the international literary world is very much alert to the 2022 centenary. Qiu is being interviewed for a Dutch documentary and there are a variety of publications underway: books about Eliot, various of the women in his life, essays and reconsiderations.

There’s also one coming from a small press in western Massachusetts.

Yes, in spite of having sworn on a bright October day in 1986, as I sat down for the first time in the London apartment where Valerie Eliot had lived since her 1957 marriage, that I would never let myself be drawn in Eliot studies, I will soon publish The Waste Land and Other Poems: 100th Anniversary International Edition.

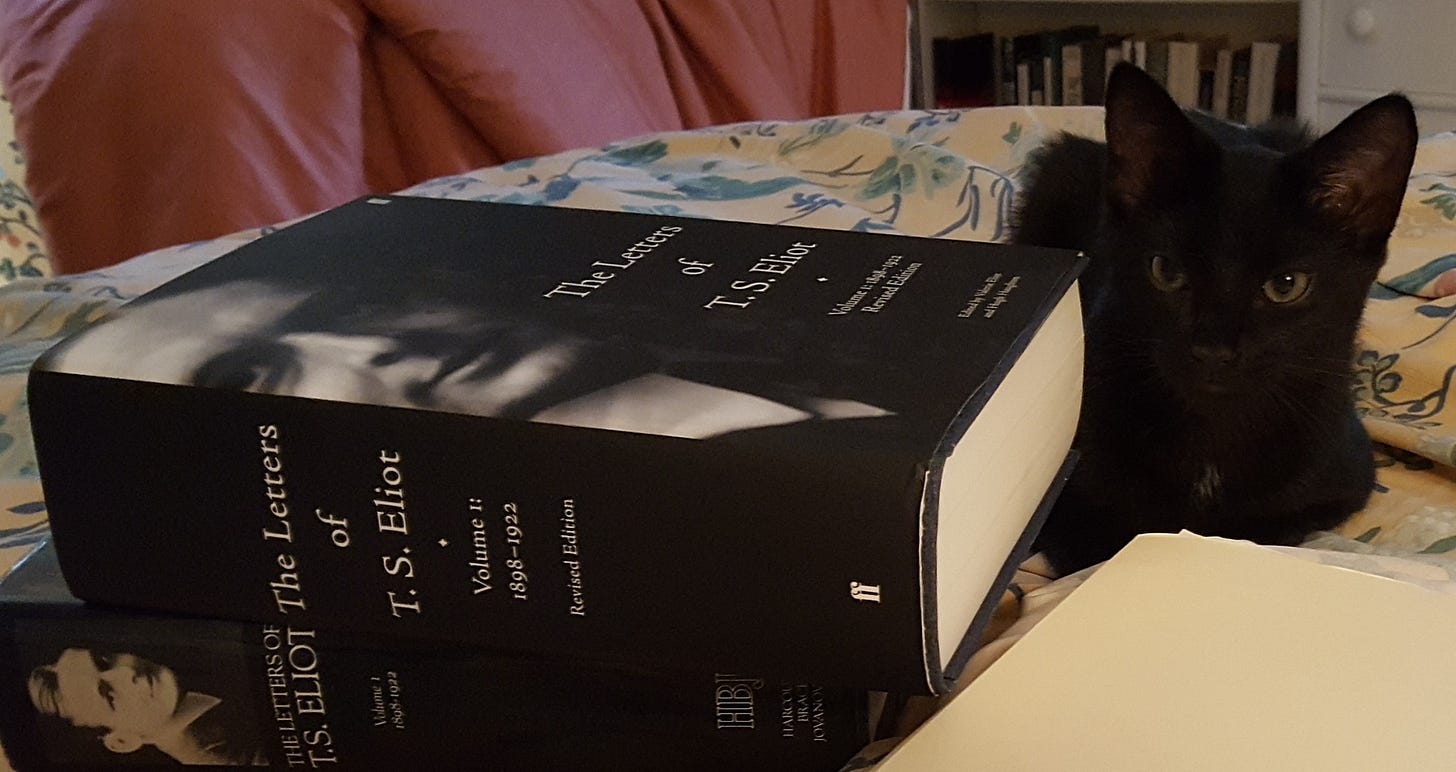

The “Never or always” in the title of this letter comes from the poem “Little Giddings” and that’s how I feel about the Eliot story. “Never,” I said, but always, after I left Valerie, it followed me (as did Eliot’s desk, which Valerie gave me while I was assisting her in editing her husband’s letters).

Soon after I moved from London to a tiny Massachusetts town, I was introduced to a woman who had been TSE’s secretary through the 1940s. This meant renewed conversations about Eliot and Valerie, and led to my writing a feature article for the Guardian Review. In turn, because by 2005 the Guardian was online, meant emails from people around the world with stories about Valerie Eliot.

Then I learned that a close friend’s mother had, as a young graduate at Bletchley Park, had a love affair with John Hayward, whom Eliot lived with for years after World War 2 and broke dramatically with when Eliot married Valerie.

I’m now resigned to my fate, especially since it includes writing about Valerie herself and other women connected with TSE.

And Berkshire Publishing will be doing something unique by publishing an edition geared to international readers. Xiaolong is writing an introduction explaining why Eliot’s poetry was so important to him as a young man in China, and how it brought him to St. Louis as a Ford Foundation Fellow. After the events of June 4, 1989 at Tiananmen Square, he stayed in the United States, started writing in English, and obtained a Ph.D. in comparative literature. His detective thrillers, featuring Chief Inspector Chen of the Shanghai police, are amongst the best-known contemporary novels set in China, translated into over 20 languages. They offer a window into China for readers who might never read a nonfiction book about China. We spoke about his work in this podcast, “QIU Xiaolong on poetry, detective fiction, & a search for cross-cultural understanding.”

Berkshire’s edition of The Waste Land will have a design based on both the original Hogarth Press edition, produced by Leonard and Virginia Woolf, and the American Boni & Liveright edition. In addition to The Waste Land, the book includes “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” “Portrait of a Lady,” “Preludes,” “Rhapsody on a Windy Night,” “The Boston Evening Transcript,” “La Figlia che Piange,” and “The Hollow Men.” The poems have wide emotional range and resonance, and the foreword by QIU Xiaolong explains how he, as a student in China, came to love Eliot’s poetry and what it has meant, and means today, to readers around the world.

Have you read T. S. Eliot’s poetry and is it (or was it) meaningful to you? Have you heard any of the scandalous stories about him, or read any of the biographies? (They exist and proliferate in spite of his prohibition and Valerie’s and the Eliot Estate’s efforts to control them.) Do you know that the musical Cats, and the universally loathed movie of 2019, are based on Eliot’s poems for children? I’d be especially glad to hear from people who have read Eliot in translation.

It occurred to me last night to look at the acknowledgements in The Green Home, published by Piatkus Books in London. They begin, “In 1988, I knew far more about ‘The Waste Land’ than I did about the ozone layer or sustainable agriculture, so I must acknowledge the work of the many environmentalists and organizations who educated and guided me.” I acknowledged, amongst others, John Elkington, who is an occasional reader of this letter, and my publisher Judy Piatkus, whom I recently, coincidentally, met again at a Zoom event. These things remind me that life so often brings us full circle. As Eliot put it,

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future,

And time future contained in time past.

Warm regards, Karen.