It was April when I started thinking about typewriters. Not because of T. S. Eliot but because of spring cleaning. I realized I had three manual typewriters and not one worked properly. I felt I should have at least one to use, in case of electricity failure, and I felt a yen to start a story on a clean white page.

While manual typewriters have a certain hipster appeal, finding someone to repair them has never been easy. Lugging them to Boston or New York did not seem feasible - it would entail two trips and be far too expensive. I went online and found a shop in Northampton, but it seemed to have vanished during the pandemic. But I live near the corner where Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York meet. I found an article about a shop in Stephentown, New York. I wrote:

I was in despair about finding someone to help with repairs on two typewriters and then checked for something in New York. I drove through Stephentown on Tuesday and actually thought I should go back sometime and explore – isn’t there a bookshop there? I trust that you are still in business!! Would be glad to drive there again soon. I think the fix with one machine could be very simple. The other, I’m not sure about. I’m also looking for a particular old machine and might ask you about that.

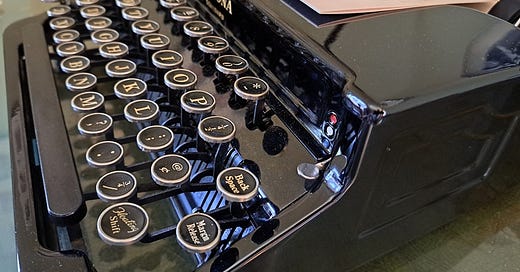

What I was thinking of was a typewriter that T. S. Eliot might have used, and it turned out that Scott Conner of Stephentown Typewriters had just the machine: a Corona flattop with a lacquer finish. You can see it above, on Eliot’s desk, in my home office in Great Barrington.

I’ve learned a lot from Scott. First, to my chagrin: never use WD40 to lubricate a typewriter. It gums them up. Second, the biggest challenge in getting an old machine up to snuff is removing years of tobacco smoke residue. Bringing my Corona to its original glossy finish took many separate cleanings, and the tobacco residue gets into every part of a machine.

I’ve also learned that there is a world of typewriter enthusiasts out there. Notable among them is Tom Hanks, who writes to typewriter shops and gives signed typewriters to people like Scott who work so hard to bring old machines to life. “Actor Tom Hanks writes to Stephentown typewriter shop.” And there’s California Typewriter, “a documentary portrait of artists, writers, and collectors who remain steadfastly loyal to the typewriter as a tool and muse.”

Why use a typewriter?

Or a record player, or pen and paper? Why read a printed book instead of an ebook? I’m clearly not the only person asking this, but I’m also writing professionally. Does it really make sense to do some of my writing on a typewriter?

I don’t have a definitive answer yet, but I can report that composing on a typewriter is different: it’s both slower and freer. I sit in front of the machine and feed in a piece of paper as smoothly as I can. (My British typing teacher, Mrs. Elma Whittle, was the author of Advanced Typing Drills, which advises a straight back and smooth, one-handed feeding of the page, keeping the other hand on the keys.) As I begin to type, the world falls away. I can’t flip to the news or check Notes, or check another file. I’m simply there with the page, my imagination free.

The machine provides boundaries, and each page is a measure (about 300 words). Each new page is a fresh start.

At first my fingers weren’t strong enough to get a consistent impression, but it hasn’t taken long to get them fit again. This is good for the hands and wrists. Secretaries in the old days could spend an entire day banging out letters and reports without getting carpal tunnel syndrome.

And because I was once an excellent typist, thanks to Mrs. Whittle, my typed pages are clean enough to scan easily. It’s little trouble to run them through Adobe Acrobat and get a draft on my computer. Of course this isn’t for everything: I’m writing this newsletter on a computer, and my work as a publisher will continue to be highly digital. But that’s not the whole world. And, as any dystopian reader will realize, if I stockpile paper and a few ribbons, I’ll be able to write even when climate change leads to extended power cuts and zombie attacks.

And I’m not the only one thinking like this.

A funny thing happened on the way to the digital utopia. We've begun to fall back in love with the very analog goods and ideas the tech gurus insisted that we no longer needed. Businesses that once looked outdated, from film photography to brick-and-mortar retail, are now springing with new life. Notebooks, records, and stationery have become cool again. Behold the Revenge of Analog.

And just a couple weeks ago: “6 [more] analog trends that are good for the soul” inthe Washington Post, and here’s a gift link.

. . . David Sax, author of The Revenge of Analog and The Future is Analog, noticed a countertrend growing as digital technologies began to take off with the advent of smartphones, streaming services and social media. The more we rely on digital technology for work, learning and socializing, “the more we seek out analog alternatives as a balance or a different way of engaging with the world,” he said.

The article lists these trends:

Film cameras

Sending letters and postcards

Print books and magazines

Vinyl records

Pens and stationery

Collecting

A Letter is Better: Love and Remembrance

And what about the desk?

Valerie Fletcher was T. S. Eliot’s secretary for 8 years before they married, and survived him for nearly 50 years. She was known for her fierce protectiveness, of his work, his words, and anything that had been his. She kept the flat they moved into after their marriage in 1957 as a kind of shrine.

There was the day I daringly took herbal teabags to work and asked if I could have some hot water. After quizzing me, Mrs. Eliot insisted on taking one of the teabags. A little later she appeared with a tray. On it there was a cup and saucer and a small white and gold teapot. "Tom always had mint tea before bed," she said. "I had to wash up the teapot." It hadn't been used since he died in 1965. (From “Dear Mrs. Eliot” in the Guardian Review.)

How then could she have given me his desk? After all, I was just the help.

While I wasn’t one of the working-class women she felt most comfortable with, I definitely kept my accomplishments under wraps. I never talked about my university successes, or about having taught a class on literary letters under a famous critic. I didn’t mention my connection with an earl and countess, or to one of the Monty Pythons - not even when she talked about Andrew Lloyd Webber.

Instead, I told stories about my little son, and or my neighborhood projects - most amusing when there were disasters, as there seemed to be rather often. I was a useful distraction, the amusing little American girl she would tell John Bodley at Fabers about when he tried to press her about when the centenary manuscript would be finished.

That narrative was disrupted when I called with the news that I’d got a book contract. I must have realized she wouldn’t like this, but I was so excited I had to tell someone.

But once I explained that the book wasn’t literary, she was magnanimous, even passing on to me a gardening book someone had sent her.

One morning over coffee she mentioned that she was expecting the delivery of a desk she had bought at auction. It was, she explained, “more suitable for a home.” But she would have to do something with the old desk, a plain deal office desk that TSE had bought secondhand on the Tottenham Court Road when they were furnishing the flat, the desk where he had typed his letters and finished The Elder Statesman.

I held my breath.

“Perhaps you could use it,” she said, “after all you have your little book to write.”

I could hardly keep from squealing. I lowered my eyes and accepted humbly. Just as I did when she offered me an apple and shooed me out the door at lunchtime.

The desk is a practical thing: it comes apart into 3 pieces that are easy to move. I put my little Amstrad computer on it and wrote Home Ecology. When I left London for upstate New York two years later, I shipped the desk along with my books and left everything else behind. And it’s been in my home office in Great Barrington for many years.

In front it is William McNeill’s chair, and on it is a lovely pot that was once a gift to Lewis Mumford. Though I am writing about women, Valerie Eliot and Sophia Mumford, these men (each of whom appears on the list “Modern Library's Top 100 Nonfiction Books of the Century”) and others are part of the story. The Corona typewriter is my latest talisman.

I love this! I'm also a typewriter maven. I write my all my first drafts on typewriters, then transfer to MS word for rewrite & editing phase. When I'm on typewriter I can wail away. I slow down when editing and the rewrite. Writing first drafts on typewriters is my version of Hemingway's dictum: Write drunk, editor sober.

The desk was his late in life and it is not where he wrote the “Four Quartets” or “The Waste Land.” I wonder where his typewriters are now? “He wrote mainly at a typewriter placed on a high stand, so that he stood up to write. Once, when he was queried about this rather odd habit, he replied, ‘It is a mystery to me how anyone can write poetry except on a typewriter.’”