The taxi driver we hired in Xi’an in April 2001 was friendly but quiet on the long drive to see the Buddha’s finger at Famen Temple. The next morning, he was much more talkative because he was upset with the Chinese government, “They are sending some soldiers, American soldiers, back to America.”

He didn’t understand why Clinton wasn’t still president. “In China, if someone does a good job, he can be president for a long time.” Chinese women, he said, liked Clinton more than Bush. They found Clinton sexy, I gathered. I was about to ask for more detail when my young son closed the conversation down by cheerily asking, “When do you hold your elections?”

Many Chinese people liked Trump at first because he was a rich businessman with big waist. I heard older people describe John Kerry as looking “presidential” - tall and patrician.

Until Russia invaded Ukraine a year ago, the US press often referred to Volodymyr Zelenskyy as “a comedian.” That moniker now seems ancient history, condescending and less than astute. But his capacity for wartime leadership isn’t something that anyone, including Zelenskyy himself, could have predicted with certainty. (It’s one of the great debates in leadership studies: are leaders born, or made?) But how he has leaned into it, passionately and pragmatically. As a former actor, Zelenskyy knows that image matters, and he has been shrewd about his wartime appearance: the army fatigues, the stubble beard, and even his posture tell a story.

But how are these images of leadership captured, shared, adapted and altered?

The Financial Times recently reviewed a show of early (1800-1850) photography1 that includes a daguerreotype2 of Queen Victoria and her children. The Queen hated the way she looked so much that she scrubbed out her own face! How reassuring to think that the woman who reigned over the British Empire was just like the rest of us. (I often think of advice a friend passed along: If you don’t like a photo of yourself, just wait 5 years.)

Victoria became queen when she was a young woman and reigned until she was old. The coins of her reign had images based on official portraits. Looking at them, I wonder what she so disliked about the daguerreotype. She obviously liked the images of her children or she would have trashed the whole thing.

I learned from the review that from the earliest days of photography there were ways to adjust or manipulate images.

The great lesson of A New Power is precisely the opposite of what the unknown portraitist presumably feared: photography could be anything but accurate and objective, put to use for propaganda and profit.

What was conceived as a technology for capturing the world as it was — art critic John Ruskin said a daguerreotype was “very nearly the same thing as carrying off the palace itself” — instead became subject to that obscure mishmash of human motives and emotions which bends reality to desire. Daguerreotypes were fragile and expensive, so most of the general public would not have had access to them; the main means of transmission was reproduction by an engraver in newspapers and magazines, line drawings accompanied by the phrase “engraved after daguerreotype” to vouchsafe their accuracy. Yet figures could easily be “cut and pasted” from separate photographs into a final engraving or reorganised to suit the artist’s eye. A daguerreotype by Antoine Claudet’s studio of Lajos Kossuth, exiled regent-president of the kingdom of Hungary, was reproduced again and again as he fundraised for an independent Hungary, but subtly altered: in an 1851 engraving, his hand lingers on a balcony railing; a year later, he’s holding a scroll. If anything, photography demanded more trust and critical engagement from viewers right from the start.

What does a leader look like?

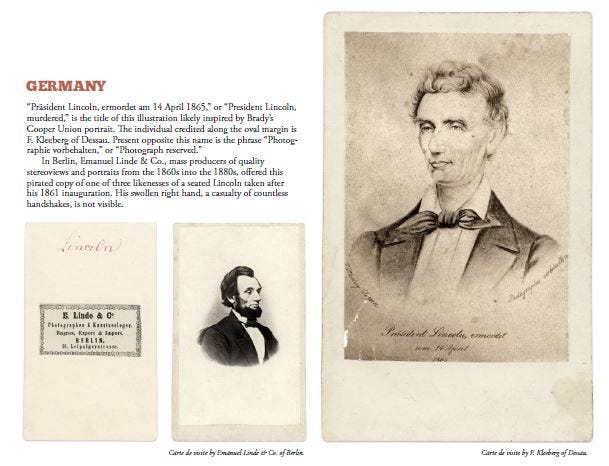

With Zelenskyy in mind, I know you’ll be intrigued by an article about portrayals of President Abraham Lincoln assembled by Chris Nelson, whose Nelson Report was for many years required reading in capitols around the world (Chris retired in 2020). The article explains Lincoln’s global influence, and shows us how his image was altered to fit the different perspectives of people around the world.

Considering the world’s fascination with the government, economics and people of the United States—and the war that engulfed the nation—it is perhaps no surprise that the president drew international interest. In Europe especially, from where its laws and religion were imported and its population rooted, Abraham Lincoln loomed large. Countries long opposed to American slavery watched him closely. His words and deeds touched workers in places with their own social and economic tensions, post the 1848 unrest which sent so many immigrants to the U.S.

Sometimes they replicated portraits directly. On other occasions, they adapted portraits, placing Lincoln’s head on another person’s body and other creative treatments, such as using a photograph for art reference to create a unique illustration.

Here’s Chris’s article at Military Images magazine (the site has a registration wall, but allows one free view before the prompt to subscribe). The magazine and the author have also given us permission to share a PDF of the published article.

Global perspectives

I’ve been recording what other people think about the United States since I took at bus to Guadalajara when I was 16. My British friends never seemed to hold back - I remember being told that Stratford-upon-Avon was “simply lousy with Americans” and a friend’s mocking imitation of the way some Americans told him that he must be glad to be visiting the greatest country on earth.

This interest of mine evolved into a 3-book set, written by authors from around the world, published towards the end of the George W. Bush era and definitely due for a new edition. Its stories go back to the colonial period.

We originally thought we could organize our coverage based on each nation’s response to key events in history, such as the American Revolution, the Civil War, the world wars, the founding of the United Nations, and so forth. What we found, however, was that this approach was hopelessly ethnocentric. All over the world, most people’s views of the United States are shaped primarily by what has transpired in their nation and how the United States was involved, or in some cases, such as the Hungarian Revolt in 1956, how the United States was not involved.

A paperback of the 3rd volume, on Issues and Ideas Shaping International Relations is available from Amazon, and is on sale at Berkshire Publishing.

When Women Leaders Resign

Speaking of appearances, what does it mean when two women who are prominent, influential heads of state, resign from office within weeks of each other? To my mind, this is a serious and worrying situation, because “strongman” leaders don’t resign. (Some even refuse to go when they lose an election.) But this writer thinks the resignations of Jacinda Ardern of New Zealand and Nicola Sturgeon of Scotland are a positive sign: “Are Norms Shifting for Female Leaders? Scotland Suggests They May Be.” Full article available here (gift link). Will this embolden the strongmen, or let people see women as quitters?

I’m wrapping up a new edition of Women and Leadership and wonder if we need to make some last-minute changes - and how to talk about the strongman model in a book about women?

Next Monday, by the way, is the US midwinter holiday, Presidents Day. It’s celebrated on the third Monday in February, because both George Washington and Abraham Lincoln had February birthdays. This is generally the start of a school holiday week, and here in the Berkshire Hills there are normally a lot of winter events. But the snow has melted and it’s been well above freezing. The tadpoles in my pond have been frisking about. Climate change means extremes: just a couple weeks ago, the renowned Salisbury Ski Jumps across the border in Connecticut were “CANCELED DUE TO HIGH WINDS AND WINDCHILL.”

A Song and Dance

In conclusion, a song that might have made President Zelenskyy smile in less dark times. (Here’s a list of ways to donate to Ukraine and help Ukrainians.) The song dates to 1965 and I still don’t understand all its references, but you’ll get the point, and enjoy the twist at the end.

Read the review here: A New Power: Photography in Britain 1800-1850.

“Produced by exposing to light a chemically treated silver-plated copper sheet set within a camera.”