It is a bold historian who concludes her book with a chapter entitled “The Politics of Creation and the Search for Truth and Beauty.” No wonder I was attracted when Pamela McVay, a contributor to our Encyclopedia of World History, asked if I might be interested in republishing a textbook she’d regained rights to. I found that it wasn’t a textbook at all, but a beautifully told history of women around the world.

Historians on the whole are fairly good writers, but this seemed to be exceptional. When I asked, Pamela told me that she admired, for example, the Nigeria-born novelist Buchi Emecheta. In the face of grim news, I find this window on the past inspiring, and hope you will find it a source of solace, too.

From Women: A World History by Pamela McVay

It was when my mother-in-law told me I did not have to follow nobody’s ideas that I learnt myself to follow my head....And that’s what I did, and I do it yet, and it’s a good way, too. — ARLONZIA PETTWAY, B. 1925, on developing her own style of quilting.

No history of women should ignore the extent to which women strive to express themselves and to understand the world. A survey of women’s creative and scholarly accomplishments through the last 500 years would fill a library of books. But it seemed best—after six chapters largely devoted to women’s struggles for freedom, security, child care, political influence, justice, and mere survival—to remind ourselves that the human spirit is not simply the victim of outside forces. Nor do women live by bread, rice, and family alone. They also need intellectual, spiritual, and creative outlets to grow as whole persons.

Yes, misogynist efforts and anti-feminist backlash seek to take away women’s gains in political, economic, sexual, and reproductive freedom. Yet more girls and women have greater access to education and training in all areas of life than ever before, resulting in a worldwide proliferation of artistic and scholarly works in all media and genres. If it is true, as a popular slogan of Second-Wave Feminism claimed, that “the personal is political,” the personal decisions of so many women to work as scholars, artists, and artisans have a political dimension.

Some Political Implications of Domestic Crafts

The most domestic and traditional of women’s activities can have powerful political meaning. Industrialization and development notwithstanding, some women still fabricate many of the objects they and their families wear and consume. Whether they are very wealthy or living in dire poverty, most women are engaged in some kind of artistic or craft production, from preparing special foodstuffs and crafting ceremonial objects to fabricating basic necessities such as clothing, furnishings, or houses. Women use crafts like sewing, weaving, basketry, cooking, and pottery not just to fulfill their own and their families’ basic needs but also to maintain cultural identity, to make political statements, and to express themselves.

Using traditional methods of craft production is one way women choose to pass on their heritage to their children and to remind themselves and others what it means to be a member of a particular community. Such a purpose for craft production has been especially important for indigenous peoples and members of minority groups, whose craft and cooking practices can help community values and lifeways survive under external threats and pressure. Rigoberta Menchu, a Guatemalan labor activist, explains that when she was growing up, the women of her community made tortillas in the traditional way every day:

It’s not the custom among our people to use a mill to grind the maize to make dough. We use a grinding stone; that is, an ancient stone passed down from our ancestors. We don’t use ovens, either. We only use wood fires to cook our tortillas. First we get up at three in the morning and start grinding and washing the nixtamal, turning it into dough by using the grinding stone. We all have different chores in the morning. Some of us wash the nixtamal, others make the fire to heat water for the coffee or whatever ... there were four women working in the house. Each ... had her job to do Whoever gets up first, lights the fire. She makes the fire, gets the wood hot and prepares everything for making tortillas. She heats the water. The one who gets up next washes the nixtamal outside, and the third one up washes the grinding stone, gets the water ready and prepares everything needed for grinding the maize. When the fire is made and the nixtamal washed, everyone starts grinding. One person grinds the maize, another grinds it a second time with a stone to make it finer, and another makes it into little balls for the tortilla. When that’s all ready, we all start making tortillas.

Corn, she explains, is the basis of Maya indigenous culture, and the methods used to cultivate, process, and cook maize shape the community in ways that it would be very difficult to reproduce by other means. Likewise, when a Navajo seeks to weave by traditional methods, she is also seeking to maintain or return to her roots and, like Rigoberta Menchu, involving her community in the process. Traditional Navajo blanket weaving requires a particular lifestyle. Ideally, the wool would come from a woman’s own sheep, which her husband, brothers, or sons herd, and which she and they follow, moving from summer to winter grounds. She should clean, comb, and dye the wool herself from fibers available locally and use a particular kind of loom and—because the fabric is made by hand and all by her and her daughters—here and there the fabric will contain stray hairs of their own woven into the whole. The pattern should look “right” when the blanket is draped over the body a certain way and may well be designed with a particular person in mind.

Thus, a Navajo blanket made by traditional methods is more than a decorative object—it stands for a commitment to living traditionally. When Ashkenazi Jewish women around the world make bread and prepare their households for the Sabbath, they are doing something similar—creating a Jewish space that not only their grandmothers and great-grandmothers but also Jewish women on the other side of the world would recognize. In Mali, in the ancient city of Jenne, women who marry into families of blacksmiths from outside ethnic groups often take up pottery making, not just to make money, but because women from blacksmith’s families have traditionally worked in that craft. Going through an apprenticeship in pottery helps a woman integrate into her new family, who often press her to take it up. Most readers can probably recall ways that special foods, gift textiles (in this author’s own circle, usually quilts), seasonal household ornaments, or the choice of particular gardening methods or plants connect them to their own family heritage.

Women also make crafts with explicit political messages. In the 1960s and 1970s the women of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, made “freedom quilts” in support of the civil rights movement. Pacific Islanders have been particularly attentive to the ways tradition becomes part of modern cultural identity and national self- awareness. For instance, Māori women and men in New Zealand and Samoan migrants in the United States and New Zealand wear tattoos in part as a way of connecting to and carrying on their traditions. And in Papua New Guinea the bilum, or net bag—a women’s craft that has spread throughout the country in the last few decades—has become one of the most important and widely recognized symbols of traditional culture and of Papuan womanhood. Each region produces its own kinds of net bags, ranging from the purely functional to the ceremonial and highly decorated.

Even though simply making craft items of a particular sort may have a broad cultural meaning, when a woman makes a particular object it is usually for a specific person, occasion, or purpose, and the actual design will often be chosen for purely aesthetic reasons. Arlonzia Pettway, quoted at the start of this chapter, is typical of the other quilters in her small town, most of whom say that although they may have gotten inspiration from formal patterns, in general they designed quilts to please themselves, in variations of patterns they saw their mothers make. The quilts themselves served an important function—they had no central heat and no fireplace in the bedrooms, so every bed needed four to six quilts. The quilts, being made mostly from the remains of old work clothes and rags, were not very sturdy, so most women needed to make several a year for their families. But each individual one was made to please the eye as much as possible using the often faded and stained materials available. Their meanings could be very specific and personal. After her husband died, one widow and her daughter made a quilt from all of her husband’s work clothes so that she could wrap herself in it and be surrounded by him. Some years, coming together to make quilts and sing was the only recreation the women had.

Like the women of Gee’s Bend, Chilean activists turned a folk art—in their case, the arpillera, applique images of rural life and landscapes sewn on burlap to make tapestries—into political protest. Working in the basements of Catholic churches with donated supplies, Chilean women in the mid-1970s and 1980s used the arpillera to document the kidnappings and disappearances of their relatives. The churches displayed and sold the tapestries to support the women and their families (who were often deeply impoverished), at once supporting the protest movement and providing the women an outlet to express their grief and pain.

Crafts, which have only recently begun to receive serious scholarly attention as art forms, can resonate through several dimensions of women’s lives and have both covert and overt political meaning. They can commemorate events and people in the life of a woman and her family, helping them keep their family or their ethnic traditions alive. They can act as an anchor for tradition while a world of unnecessary change tries to sweep families along. They can unite women for common purposes, function as a form of political advertisement, and pay for social and political movements.

The text above comes from the concluding chapter in Women: A World History, by Pamela McVay of Ursuline College. The book (300 pages) is available from Berkshire Publishing, and can be found on Amazon as well as other ebook platforms.

Restoring the broken

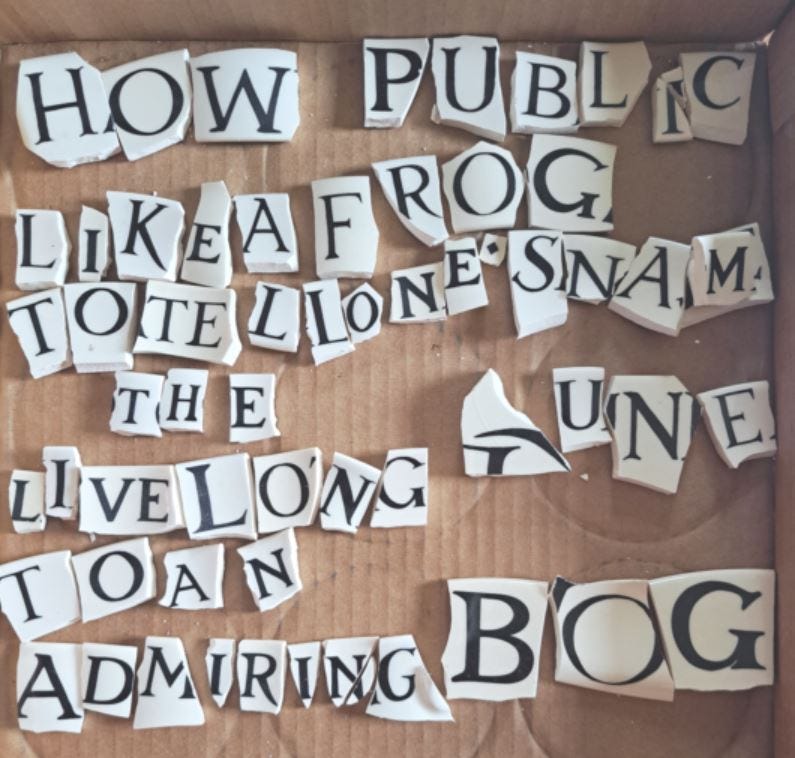

My own favorite craft is pique-assiette mosaic making (gallery). My project of the moment is a wall piece with an Emily Dickinson poem.

I’m Nobody! Who are you? Are you – Nobody – too? Then there’s a pair of us! Don’t tell! they’d advertise – you know! How dreary – to be – Somebody! How public – like a Frog – To tell one’s name – the livelong June – To an admiring Bog!

Making this type of mosaic is, of course, a kind of recycling. But I think the reason it suits me is that it’s very much like publishing, especially when I have put together a big team to do a complicated project, like an encyclopedia with a thousand authors. Different topics, voices, perspectives, and language skills, all to be shaped into a coherent and harmonious whole.

I now have to create a frog or two to complete the composition. Emily Dickinson, who also lived in western Massachusetts, must have watched, as I do, the antics of green frogs (that’s the species, not just the color). She knew just what showboats green frogs are! Here are two that live in my tiny pond. They are deep in the mud, under the ice, right now, but I’m sure they’ll be out as soon as things warm a bit. I saw a tadpole swimming a couple weeks ago, when we had a brief thaw.

Perhaps even more appropriate to the moment is the Japanese art of kintsugi. Kintsugi is an art based on the idea that we can find and create beauty in spite of flaws and scars and breakage. Here are two pieces I’ve repaired recently.

Do you have a craft, or a craft you want to take up?