Coming together: let's do better

Meeting face to face again is an opportunity to rethink what we value

A year ago today, I saw my neighbors face to face for the last time. A dozen of us crowded around a long table at Number 10, a restaurant/bar just down the street from my house. It was the monthly meetup for TheHillGB, a neighborhood email listserv I started in 2010.

It took years to get the face-to-face, third-place thing going. Somehow people who are quite lively in an email group (we have some notable humorists) don’t want to join a real live gathering.

I sympathize, actually. Real life is risky. You can get stuck in a corner with a bore or a lech, and conversations can devolve into complaints about town government or countertop comparisons (this is a big issue for some, but not for me).

Nonetheless, I truly believe in the value of conversation and that conversation is something of an art. And I want to live in a neighborhood where people know and care for one another.

At that point, March 5, 2020, we knew about COVID-19. After all, I was there at Number 10 only because my trip to China had been canceled. I must have realized that crowding together - this was well before masks - might not be the best idea. But we had a great time, never dreaming that life would, within days, be turned upside down.

I still see my neighbors, but only while we’re out walking. Everyone is masked and right now we’re bundled up in winter clothes. We lack most of the markers that help us identify people. I’ve walked past people more than once before finally recognizing a tilt of the shoulders or the relative heights of a couple. Some people recognize me only when they hear my voice (I’m making a big effort to say hullo to everyone I pass).

Indeed, I occasionally have mask-free conversations with my nearest neighbor, shouting across the lawn. But we’re not close enough to see each other’s faces fully. You have to be fairly close to know if someone is looking worried or tired, whether she’s in a hurry or looks like she might want to hang out for a minute and talk about spring plantings.

When it’s warmer, maybe we’ll make some outdoor spaces in the neighborhood where we can hang out together, until we can go back to Number 10. I’m wondering how this bench, stationed on a corner just up the hill, might serve a new role as we transition.

Then, of course, there’s the online world that is all too much of life right now. I was on a Zoom with the ever-larger group that gathers, now that we’re not limited to a conference room at CUNY, for the monthly Women Writing Women’s Lives seminar. It’s an illustrious group of women and I’m really glad to be part of it. But I realized when it was over, after having heard from several members I might want to talk to sometime, that I might not recognize them in real life. Not, anyway, with the certainty I’d feel if we’d been in the same room, because their faces were flattened into a single image with whatever was behind them. I’m really distracted by people’s rooms and even more by virtual backgrounds. That the wobbly line around people’s heads mesmerizes me.

The most important thing to do to improve Zoom is really simple: turn off the self-view (click into the menu next to your face, then Hide Myself). We’re not meant to look at ourselves while talking to other people and it does weird things to our brains. Apparently looking at ourselves is a big contributor to Zoom fatigue.

Try the phone. One study came up with the groundbreaking conclusion that maybe we could just talk to each other.

Consider a letter, or a long, heartfelt email. I know, this makes me sound like an old fogey. But as I explained in A Letter is Better, there is something very special that happens in terms of imagination and empathy when you sit down alone and use words, limited as they are, to reach out to another person. One of the most satisfying things for me this past year has been a correspondence with a woman in England whom I have never met. She uses email, but she writes letters.

I could share links to all the articles and studies I’ve read this week, but maybe I should make that a reward for subscribing ;-). I’m not a fan of footnotes, but I could go there if pressed. Substack, curse the developers, seems to have a footnote feature.

Of course we hear about computer facial recognition and how it’s being used for surveillance. Human facial recognition is much more subtle, weird, and wonderful. I’ve read that adults can maintain familiar relationships with only 150 people but can recognize 6,000 faces. That led me to ask about the process of how we learn to relate to and empathize with other people. A recent study analyzed what we “see” or “read” in masked faces, asking to what extent we can judge emotion in another person without seeing the lower half of their face. Not much, it seems. It’s especially hard to read sadness, anger, and fear accurately. (Blocking eyes with sunglasses has a similar effect, by the way.)

For those of us who’ve had plenty of life experience, this isn’t such a problem. We’ll pick up our skills again. But babies and small children learn to relate to others based on real-life experience. Face-to-face interaction matters, and they are not getting as much of it as they really need.

Of course we need to take safety precautions now, but I hope we’ll make all the more effort when this is over to get away from our screens and into one another’s company.

The Future of Third Places

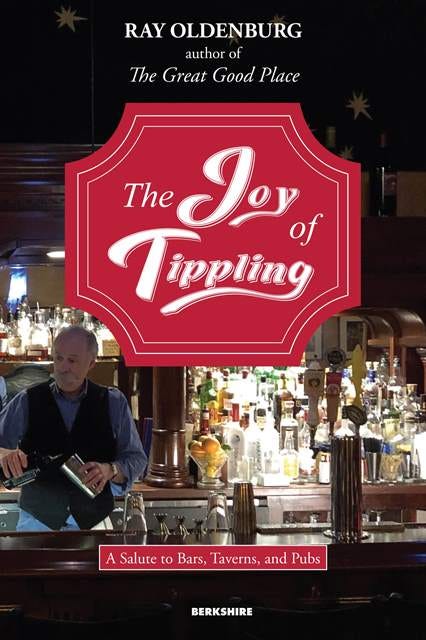

One of my projects for the next year or two is a book I’m coauthoring with Ray Oldenburg, who coined the term “third place” in his acclaimed The Great Good Place, first published in 1989. I was a young environmental writer and a friend gave me his book, which kicked off my interest in the connection between sustainability and community. For 20 years, I corresponded with Ray, finally meeting him in 2012. He said he was too old to do a new edition, though the book was still in print and selling steadily. I looked for a coauthor for him, and when I couldn’t find the right person, we decided I should take it on.

Right after the lockdowns started last year, a journalist at WGBH in Boston contacted us to ask what happens to our communities when all the third places shut down at once. On Tuesday, I was interviewed by another journalist writing for the Atlantic CityLab. She was asking about the loss of third places and alternatives that arose in the wake of the pandemic, and what physical third places might look like post-COVID.

The conversation made me realize how much my thinking about third places is shaped by years in England, where pubs remain, in spite of many challenges, an essential part of life. I’m sure part of what got me involved in sports once I moved to London after college is that sports in the UK always involves socializing. In fact, my softball team, the Artful Dodgers, had t-shirts sponsored by the pub we always went to.

Americans tend to confuse third places with public spaces. Both matter, but they are not the same thing. A third place is where conversation flourishes, where you get to know people (not intimately, but it has to be more than just a name), and where strangers are welcome. That last point has come to seem much more important as we talk about social and racial equity, and about political divides (red/blue, rural/urban, progressive/moderate). Third places are enormously important for cultivating what sociologists call “bridging” social capital - a sense of common ground and community humanity for people who aren’t part of the same social or ethnic or kinship group.

Now, as Ray Oldenburg’s sidekick, I field inquiries from other countries. I had a talk with someone from the French Red Cross, which is using the third-place concept in projects aimed at integrating and supporting immigrants. I’m looking forward to a call about a project in Norway, and find myself wondering about third places in China. I was taken to a start-up in Beijing a few years ago, a combined bookstore, teahouse, and meeting place, but wonder if such places can thrive today, given the pandemic and the political climate? Should government subsidize or somehow support third places, or is this a role for churches and other existing organizations? If you have any ideas, I’d love to hear.

Ray’s latest book is The Joy of Tippling: A Salute to Bars, Taverns, and Pubs. More about third places from me: What is a “third place,” and do you have one? and Religion for the rest of us.

Seeing the World

A year ago I was supposed to be Schwarzman College in Beijing talking about Chinese food and gastrodiplomacy, and I’ve been cooking a lot of Chinese dishes of late (I’m loving the recipes at the blog Omnivore’s Cookbook) . As I sliced green onions one evening, in a diagonal “horse ear” cut, I remembered a memoir about teaching in China. Peter Hessler asks his class to describe a beautiful woman. The students use a variety of images familiar to Westerners: “mouth as red as roses” and “like a red cherry.”

But how about “Her skin is white and soft, like cooked fat”? Or “her fingers are so slender that scallions can’t compare with them” and “her fingers are slim as the root of onion.”

It seemed very strange to me, yet the onions I was slicing that evening were quite lovely. It was, I decided, another lesson about seeing the world in a different way!

River Town, published in 2001, is a wonderful memoir, and even more interesting today because it shows a China opening to the world. The story of Hessler’s introducing his students to Shakespeare is unforgettable.

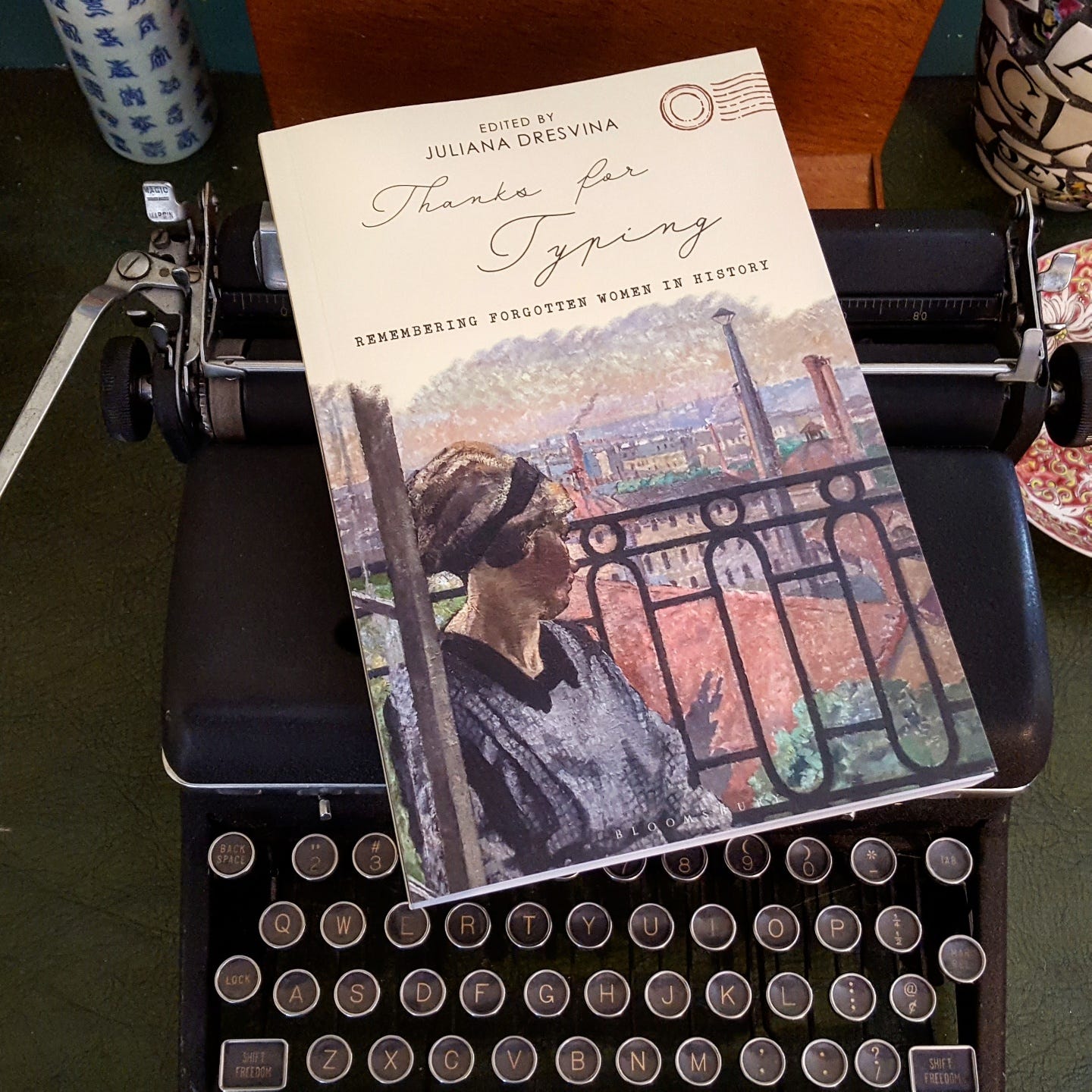

Thanks for Typing

Thanks for Typing: Remembering Forgotten Women in History from Bloomsbury Academic began with a Twitter hashtag, #thanksfortyping, and the contributors met at an Oxford conference in March 2018. Once travel is possible again, we’re hoping to organize another conference, perhaps in the United States, perhaps in Finland (where this topic seems to have attracted a lot of scholarly interest). If you would like to read my chapter about Valerie Eliot and Sophia Mumford (the wives of T. S. Eliot and Lewis Mumford), please drop me a line by replying to this email.

Hi Karen, I love your emails. I moved to GB in 2013 not knowing a soul. I did not come here regularly as a child, like many other transplants. The Gypsy Joint was here then and I would gather up my courage to go in, to listen to the music and sip a drink. The first time I went I looked for a seat where I could hide, but watch the activity. Right away, a couple seated at the bar waved me over warmly to an empty spot beside them. We talked all night about ourselves, the Berkshires, and our kids who are exactly the same age. What a great experience. I miss the Gypsy Joint. Fuel is not the same. I live on the East side of Main St. , down from the library. Of course I love the library, but I sometimes feel we are second class citizens as we are not organized like you on the Hill. We have few, if any trick or treaters down here, but we do have bears!

The public library is a cherished third place where people take a personal interest in one another. In our town of 5,000ish population, the library staff welcomes all and warmly treats all with respect. People support one another. Though the pandemic has altered/limited services, I have no doubt that in a few months more normal services will open up and patrons will love it!