What I heard from readers about memory & publishing (no, I'm not out of a job yet)

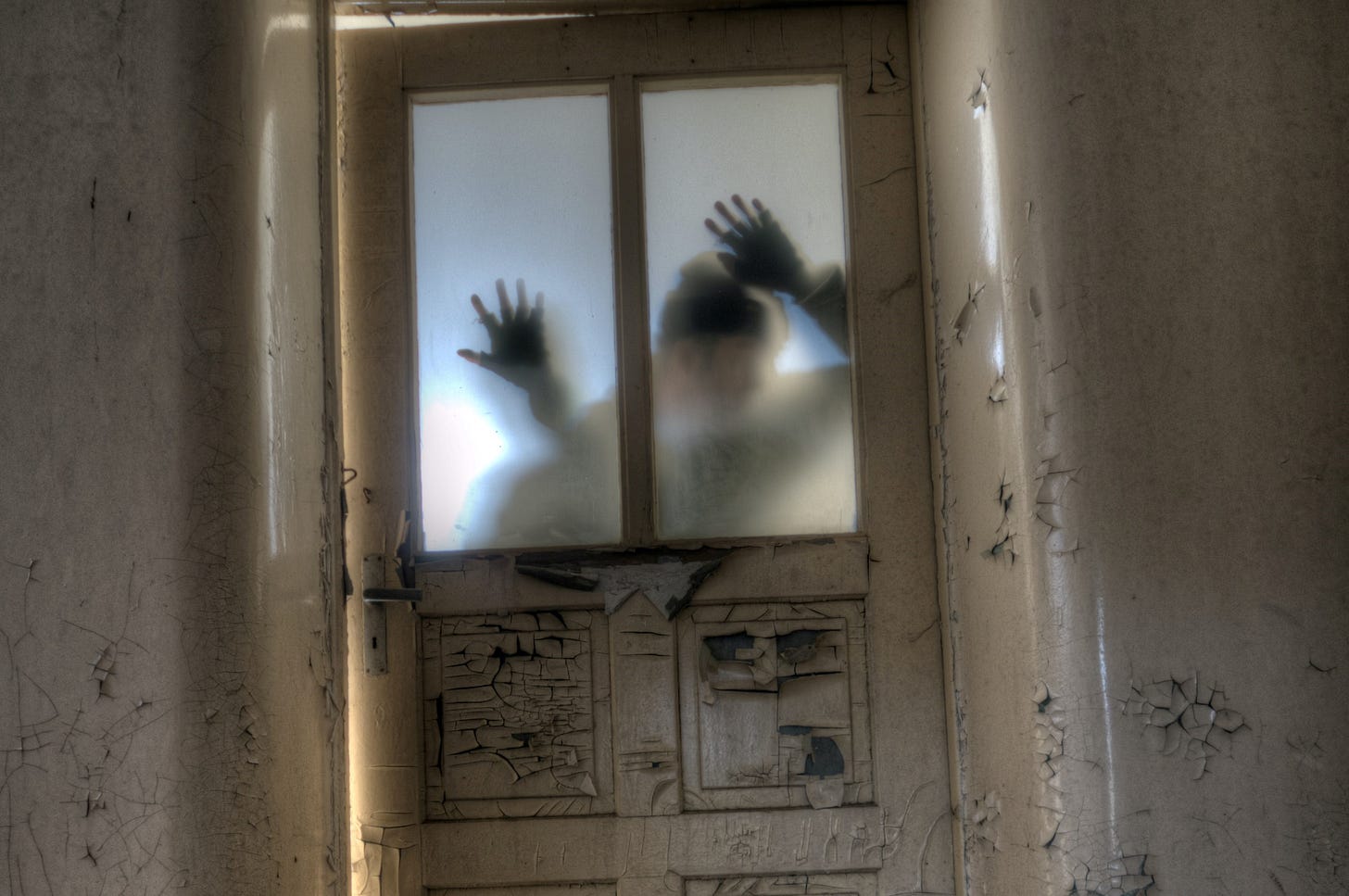

The zombies are still walking, but that's not the end of the story.

My letter about memory produced some fascinating emails.

Jerry Cohen, who is 91 and as active in Chinese legal issues and human rights efforts, and also writing a memoir, pointed out that a review late in life can reveal a narrative we didn’t recognize at the time. There’s a lesson in that for us at any age: we do sometimes need to get a birds’ eye view of our own life trajectories. Read one of Jerry’s Washington Post opinion pieces here or his blog.

Denis Hayes strongly agreed that truth matters, even if human memory is fallible. He gave me a good way to look at Brian Williams “mistake” about being in a helicopter that was fired on. That’s like “remembering” escaping from the World Trade Center on 9/11 when you were working in an office in midtown. This article about Denis in Rolling Stone has a hilarious and timely lede: “Denis Hayes is the Mark Zuckerberg of the environmental movement, if you can imagine Mark Zuckerberg with a conscience and a lot less cash.”

And Richard Charkin had an example of the way a paper record still matters. He says he “regaled people for years with my memories of a trip to Morocco in 1967. The story was recounted all over the place because of various people we met etc. Over time I began to doubt my own memory until letters from one of my fellow travellers were published which (more or less) confirmed I wasn’t lying.”

The letters were written to that friend’s parents. (There was a time when that was expected, that young people would send letters home at regular intervals to reassure the old folks.) The details, including one about Richard’s calling the Rolling Stones’s hotel suite in Morocco, are there in the letters, which were published in Remembered for a While, by and about the musician Nick Drake.

Richard is one of my favorite publishing people, former CE of Macmillan and then Bloomsbury, and now, in his supposed retirement, running his own small press. He’s the one who added further points to my criticism of zombie publishing, saying that the slowness isn’t the publisher’s fault but the result of inefficiencies in book retailing, serialization, and related marketing activities.

And he points out that there is a chasm between supply and demand. Everyone seems to want to be published, but who sits down to read a book in the evening, instead of watching TV series or adding to Mark Zuckerburg’s bank balance?

I do read in the evening, but I confess I’m partial to detective dramas and I read a lot of old books. For example, I’m now immersed in George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda. And a couple of books of those books have enhanced my thinking about memory.

I see that I was naive in thinking I could rely on verbal narratives. I learned from William Shaw’s Birdwatcher that birdwatchers have a term that means saying you’ve seen a rare species when you really haven’t, because their whole enterprise depends on being able to trust the observations of others. They call it “stringing” and will ban incorrigible “stringers” from their community.

And we can’t discount imagination. I picked up Daisy Bates in the Desert, a curious and beautiful biographical narrative by Julia Blackburn, and read that Daisy Bates “left a detailed record of her life . . . [b]ut very little of what this strange woman tells about herself is true. For her there were no boundaries separating experience from imagination; she inhabited a world filled with events that could not have taken place, with people she had never met.”

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that this example coming from Australia, land of the aboriginal dreamtime. Of course many writers have simply written novels based on their real-life events. This includes everything from David Copperfield and Little Women to Out of Africa and Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit. In literature, lines blur. In real life, we really need them to stay crisp and clear.

I’d love to hear from anyone who tries the closed-eye method for memory recovery. And about how you have tested or proved your favorite stories.

Zombie publishing

A lot of people read my letter about zombie publishing and unfortunately they agreed with me. I hoped someone would tell me I was dead wrong.

In fact, I heard about structural problems in the industry I hadn’t thought about, and why it ticks along anyway, while self-publishing surges. Both the US Authors Guild and the UK Society of Authors now offer as much information for self-published authors (services, marketing, distribution) as for those who are traditionally published (query letters, agents, contracts.

Most self-published books are vanity publications, and the authors are often exploited by shrewd businesses that know how to make use of people’s vanity.

But there’s no reason serious, talented, enduring authors can’t publish independently. I think of the first UK edition of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, published by Virginia and Leonard Woolf at their Hogarth Press.

As we prepare a centenary edition of that famous poem, I’ll be thinking of the Hogarth Press and wishing I’d come up with a more interesting name for mine than simply Berkshire! (At least our Chinese name is poetic.)

But publishing well is a difficult, highly skilled enterprise. Technology and globalization have opened new doors, and presented us with daunting challenges. I’ve spent time lately trying to understand the creation and use of book metadata, and it’s a ridiculous, inefficient, mind-boggling, time-wasting, and utterly necessary part of what we do today.

Where does that leave me, in terms of the new trade publishing I have in mind? I’m still not sure about finding the people I will need, but I’ve had some encouraging conversations and have a back-of-the-envelope game plan. If you think you (or someone you know) might want to be involved in shaping a new venture, do drop me a line.

Penn Press

I need first to clarify that I have not resigned from my job as publisher here at Berkshire, as a few readers thought. One even congratulated me on landing on my feet in this new job.

I did resign from Penn Press, but there I was merely a member of the board of trustees. Berkshire is my own company and I can’t resign (though there have been a few times when I would have liked to, and once came to tears over it).

Don’t blame director Mary Francis for everything that happened. She wasn’t at the press when the Richard Vague book deal was made, and her trying to get me not to put my resignation in writing was surely done at the behest of the provost, Wendell Pritchard, who represents the university’s president and holds the purse strings. Most publishing people care a great deal about editorial independence and would hate to be instructed to publish a big donor’s books. But they also need a job and don’t relish conflict with those in power.

Some people wrote to say that I’d been brave in resigning. That’s kind, but I don’t deserve that. I was a whistleblower of sorts, but it didn’t mean losing a salary (serving on the board was unpaid) or being sued or being attacked on Twitter (when I read about Twitter mobs I imagine the movie The Birds).

The bravery, such as it was, consisted only in not going quietly. Even one of my T. S. Eliot contacts, in quite another sector in the academic world, had heard about my resignation. And it’s led to some good things. One correspondent happened to notice that I am working on a book about women and power, and offered to look at what I was writing. Our exchanges have provided new material as well as stringent criticism, a surprising and welcome result of my resignation.

As ever, thanks for reading!

I agree with you about most memoirs and some biographies. But there are some that are just fun reads, like Bill Bryson's "Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid" or Richard Feynman's "Surely You're Joking." I'm also a sucker for interesting narrative histories, like Colleen P:aeff's "The Great Stink" or Christine Corton's "London Fog."