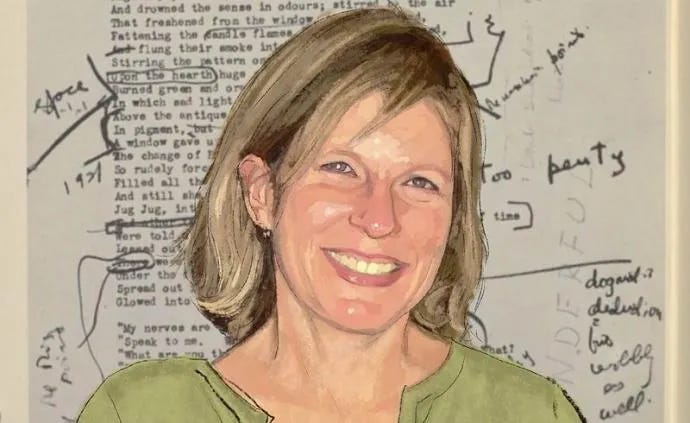

I’ve met many people who want to know more about China, and I’ve published books aiming to give the Western reader ways to understand China’s complex history and culture. The image that’s always come to mind is the window - windows into China. There’s a reason, you see, for the photo I chose for the cover of the Encyclopedia of China.

I keep thinking of things that were a surprise to me when I first went to China. You wouldn’t know, for example, from most English-language reporting that the Chinese have a great sense of humor, sometimes simply uproarious but often satirical. Here is a viral joke reacting to the government’s hopes for boomerang or “revenge” spending after the pandemic: “[Officials] thought we would seek ‘revenge’ but underestimated our compassion. We have already let go of grudges”.

Or a “Chinese CEO who complains that Chinese LLMs are not even allowed to count to 10 because the numbers 8 and 9 are associated with Tiananmen.” For historical context, here’s Professor Kristin Stapleton’s article on Chinese humor from the Encyclopedia of China.

Poetry and fiction - including detective fiction - also offer a window into China. I recorded this podcast about Chinese and English poetry and the poetic impulse with Qiu Xiaolong, best known as the author of award-winning Inspector Chen series of detective novels set in Shanghai.

Poetry in English and Chinese

Karen Christensen, publisher and writer, in conversation with novelist and poet Qiu Xiaolong, talking about the poetic impulse and the differences between poetry in English and Chinese. Towards the e…

I reread the Inspector Chen series this winter. I was missing China and realized that the novels’ publication parallels the years when I was visiting China and working on China-related projects. When I read about the constrained housing of some of the characters, I remembered visiting an apartment in Beijing in 2002. It was the home of an executive woman at a tech company and she was proud to have her own place. To my astonishment, there was no separate bathroom and I’m not sure there was hot water. The kitchen had a single heating unit and a concrete sink. If you want to get a sense of the changes Chinese people have experienced over the past 20 years or so, as well as lots of poetic references (Inspector Chen, like his creator, is a published poet and the translator of T S Eliot into Chinese), these books are just the ticket.

They are published in English, French, Italian, and Spanish, too, and bring us up to the COVID-19 and surveillance era.

More than two million copies of the Inspector Chen sold worldwide, and translation into twenty languages. TIME Magazine: Death of a Red Heroine: The 100 Best Mystery and Thriller Books of All Time. Oct 3, 2023. With a panel of celebrated authors — Megan Abbott, Harlan Coben, S.A. Cosby, Gillian Flynn, Tana French, Rachel Howzell Hall, and Sujata Massey — TIME presents the most gripping, twist-filled, satisfying, and influential mystery and thriller books, in chronological order beginning in the 1800s. And here's why Qiu's Death of a Red Heroine made the list.

Qiu Xiaolong’s new venture is detective novels set in ancient China, with the famous Judge Dee as the main character. The second comes out soon. The first, which got a starred review in Publishers Weekly, has a woman poet as one of the central figures, and we talked a bit about her in this podcast about the differences between Chinese and English poetry, the challenge of translation, and the poetic impulse.

Xiaolong and I have been talking for a while. Still online is our dialogue published in the Shanghai Review of Books.

We were celebrating the centenary of The Waste Land, and our publication of a special edition of T S Eliot’s early poems, with a conversation about my work with Valerie Eliot. You can read the article (in Chinese or in English or another language with Google Translate) at this link.

PS: I turned to the Encyclopedia of China to get some historical background before recording the podcast, and think you’ll find this article on Chinese poetry by Professor Robert Hegel an excellent, and very short, introduction.