A better world is possible. But we have to make it happen.

I’ve hesitated for months about writing a new 2024 version of my first book, Home Ecology. As you may know, last year I started a second Substack newsletter with that title. But a newsletter is not enough. Books aren’t enough either, but they are translated and serialized and quoted, and they endure.

Part of my hesitation is practical - a lot of effort, unpredictable reward, and many other commitments. But it’s also a hesitation to admit to a real interest in and love of domestic life and homemaking. I wasn’t thrilled when magazine articles and BBC interviewers treated me as a sweet young housewife or when a friend said I had a future as the “Green Martha Stewart.” A big-hitter, male environmentalist friend was patronizing about what he called “baking soda advice.”

What’s encouraged me now is a thread I see running through the lives of accomplished women: the desire to see life as a whole, to connect the personal and the political and the literary and artistic aspects of our lives. I’d like to introduce a few women - women you probably haven’t heard of - who shared this desire, and who took what I would argue is a systems approach to the way we live.

Here’s a passage from Carl Rollyson’s chapter “The Way We Live (1944-6)” in To be a Woman: The life of Jill Craigie, which may be my all-time favorite biography:

When Jill was not reading Sylvia on the suffragettes, she was reading Lewis Mumford. 'I'd read everything Lewis Mumford had written. I like to get one author and read everything that he's written on — usually it was "he" then... I read nearly all the books of the architects... I was interested in the arts, and home-making, I suppose not having a home — I was very interested in the creation of homes.' Indeed, the arts and home-making were inseparable in the minds of both Jill Craigie and Lewis Mumford (1895—1990). Like William Morris, Mumford was an 'encyclopaedist', to use Michael Foot's term, 'who seeks to embrace and relate all forms of knowledge; a popular philosopher, if you like, who does not care a fig for demarcation disputes with scientists, archaeologists, biologists and the rest'.

Biographer, literary critic, architectural historian, an anthropologist of sorts and an urbanist, Mumford was a synthesizer who helped Jill fuse her feminism, her socialism and her desire to make a home. Jill met Mumford on his trips to England, and he inscribed several of his books to her, acknowledging in one of them, The Culture of the Cities (1938), her film about the postwar reconstruction of Plymouth, The Way We Live, and the affinity he felt for its director. In her album about the making of the film, Jill placed a photograph that had been taken of the two of them in Plymouth.

Jill Craigie’s story is told by American biographer Carl Rollyson, who deals deftly and unflinchingly with issues writers often avoid: the conflict, in this case, between her own career and her devotion to the career of her husband, Michael Foot, a British Labour Party icon. Infidelity and sexual desire have a role in the story, too. Rollyson’s admiration for Craigie is clear, as is his commitment to telling a complete, multi-faceted story. This led to Rollyson’s breach with Michael Foot after years of friendship. His recent podcast asks “How close is too close when it comes to the biography subject?” in A Life in Biography.

Craigie’s work as a documentary filmmaker is explored in a recent film Independent Miss Craigie. It is only available in the UK, but the trailer is on YouTube.

Reading about Jill Craigie’s years political wife and homemaker and hostess, and about the book on early feminists she never completed (I am hoping, however, to bring it into print), brought to mind a passage from a letter Lewis Mumford wrote to Sophia Wittenberg, the young woman he was in love with, when he was 24:

“I thought of all the patient, talented women who had hidden their fame under a bushel in order that their husband's light might shine the more brilliantly—there were Jane Carlyle and Lucy Wordsworth for example—and the thought of all these thorny sacrifices made me sad, and I prayed that my masculine conceit might never stay with me long enough to permit me to let such a wrong occur to any woman that I loved.”

A writer named Florence Becker Lennon (FBL) was a friend of both Lewis and Sophia and encouraged their relationship - even giving them an evening alone together, for the first time, in her apartment. Eventually, Lewis persuaded Sophia to marry him, and over time she became convinced that she had no ambition except to be a wife and mother and homemaker.

Ten years later, however, Sophia faced a crisis over Lewis’s love affairs and it was Florence she wrote to - not telling the whole story, but crying out for help as she tried to make sense of what was happening and what her life was all about.

FBL encouraged her to write and not to be daunted by Lewis’s success. She lavished praise on Sophie in long, lively letters that barely mentioned her own difficulties. She herself was juggling motherhood and writing, and trying to figure out how to live and how to love - a perpetual question for women.

Florence was concerned about political issues and the environment, summed up as “global housekeeping” in the introduction to her papers, now at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Known as the poet laureate of Boulder, Colorado, she was a fixture at the Boulder Public Library for years, as this charming short documentary explains.

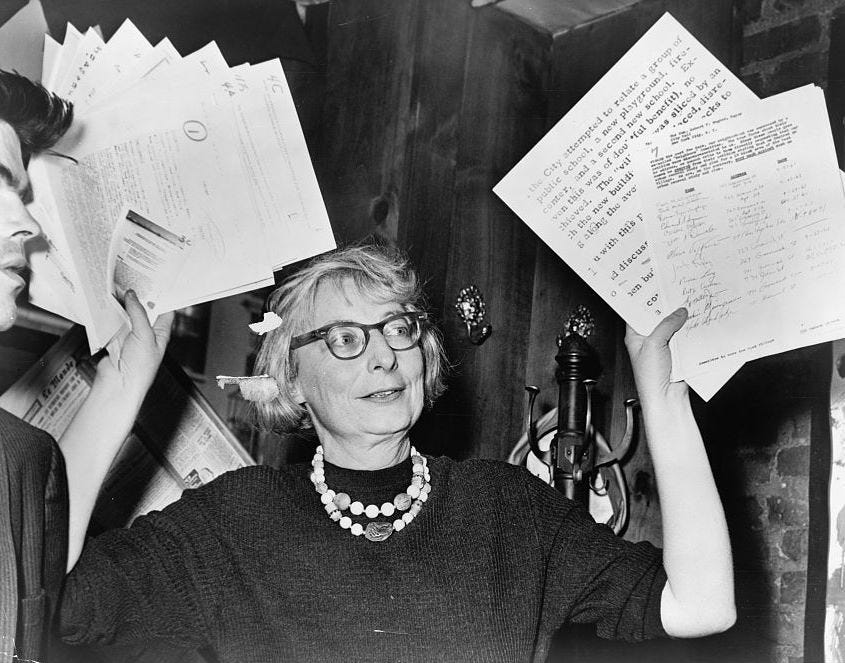

Another connection with Lewis Mumford comes from the story of Jane Jacobs. In the early sixties, Mumford was renowned for his writing on cities, and he was angered by Jacobs’s less than reverent references to him in her first book The Life and Death of Great American Cities. His New Yorker “Skyline” review (he wrote regularly for the New Yorker for over 40 years) of the book was entitled "Mother Jacobs' Home Remedies for Urban Cancer." Peter Laurence, author of Becoming Jane Jacobs, explains:

The title really says it all: Jacobs was a woman and her book was obsessed with what Mumford regarded as the particularly feminine concern of personal safety. Her best ideas were small-scale and domestic, the view of the street from the kitchen window.

What a contrast with his reaction to Jill Craigie! But Craigie was an admirer of the great Lewis Mumford, not a challenger. And Craigie was a beautiful woman with considerable charm. When I read Rollyson’s account of the friendship between Craigie and Mumford, I couldn’t help but think it was lucky they lived on different sides of the Atlantic - though by the time they knew each other, Mumford had, as far as is known, stopped the extramarital affairs.

It’s often mentioned that Jacobs had only a high-school education, but rarely does anyone tell us that the same was true of Lewis Mumford - he taught at Penn and Stanford and MIT, but he did not have a college degree.

I found earlier examples. There’s Harriet Beecher Stowe, whom President Abraham Lincoln called “the little woman who wrote the book [the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin] that started this great war,” also wrote The American Woman's Home. Novelist Edith Wharton wrote The Decoration of Houses. (“Doors should always swing into a room. This facilitates entrance and gives the hospitable impression that everything is made easy to those who are coming in.”

Finally, I want to mention a US scientist who inspires some of today’s best thinking on sustainability, and had a desire to put principles into practice at home.

Donella (Dana) Meadows and her coauthors faced a media firestorm when their book, Limits to Growth, was published in 1971. She ended up leaving Harvard to start a new life in rural New Hampshire with her co-author husband Dennis Meadows. They aimed to model a life within limits, and to prepare for the collapse they expected. That story is told on the Tipping Point podcast: “50 years ago, they told us what was coming. Why were they ignored?” A podcast about the true-crime story of "The Limits to Growth": The study, the backlash – and its legacy.

The corporate reaction was similar to the fierce criticism and media attacks Rachel Carson received after publishing Silent Spring, the book consistently credited with starting the US and global environmental movement, a decade earlier. Carson died of cancer at 56, not long after Silent Spring was published, won the National Book Award, and became an international bestseller. We included her on the cover of the new Women & Leadership as well as a short biography that explains how a quiet, shy scientist found herself facing major media attacks and testifying before Congress.

One reason to listen to the Tipping Point podcast is that it explains the ebb and flow of public interest in the environment. There was a surge in the late sixties and early seventies, a resurgence 20 years later (which is when I stepped in), and after 2012, another 20-year interval, the growing concern, and also conflict, over issues that were clear to scientists and environmentalists half a century ago.

Looking at women today, one notable figure is British economist Kate Raworth, known for “doughnut economics,” who considers Meadows an inspiring figure and was interviewed in the Limits to Growth podcast. But Raworth had been mentioned to me before and I pulled up the old emails to see who had told me about her. One was an eccentric Chinese finance guy who reads widely in English, and the other a literary friend from college who had by chance heard Raworth speak on a panel with two male economists. “She ate their lunch,” said my friend.

Is there some common element in women’s thinking about widely varied issues, and a special willingness to challenge the status quo (as both Meadows and Raworth do, notably arguing that GDP is a terrible measure for human progress)?

Meadows and her colleagues were naive in thinking that facts and data would be enough to change the direction of Western civilization. They didn’t really grasp how much some people are motivated by a desire for money and power and status, or how often we humans resist change of any kind. But their analysis of the problem was spot-on. This passage made me extremely glad that I published a volume called Measurements, Indicators, and Research Methods for Sustainability.

We need indicators that give people an idea of whether their environment is getting better or worse. I have just come from a conference of resource analysts who began discussing how to create such an indicator. We quickly bogged down in complexity – how can we have one number when there are dozens of incommensurate resources? What can we do about inadequate data? How can we even measure such complicated things?

The economists apparently did not have such qualms when they invented the GNP [Gross National Product], which is an aggregate measure of hundreds of distinct economic activities, which had never before been measured, and which required an incredible effort in data-gathering. Nonetheless, within 50 years virtually all countries in the world have learned to calculate some semblance of a GNP statistic, and more important, all countries have come to rank themselves and set their goals by that statistic, not because it’s a worthy index of human welfare, but because it’s the only index they’ve got.

Probably the single most effective thing the ecological community could do would be to agree upon and support an ecological indicator, for single nations and for the world as a whole. It could be the Audubon Christmas bird count, the density of lichens, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the area of standing tropical forest, the number of miles of unpolluted beach per person, the amount of silt in the Mississippi River, or some weighted average of all these. Something, however imperfect, is better than nothing. Read more.

Incidentally, Limits to Growth is said to be the bestselling environmental book of all time (30 million copies sold worldwide according to one source), far exceeding sales of Silent Spring.