A Du Bois Discovery

Newly arranged as the author intended: The Autobiography of W E B Du Bois, Great Barrington Edition.

I have a small triumph to share: my discovery that previous editions of The Autobiography of W. E. B. Du Bois, including the Oxford edition, part of a series edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., are not arranged and dedicated in accordance with Du Bois’s own instructions. I’m delighted to tell you that Berkshire Publishing will be publishing The Autobiography as well as his landmark Souls of Black Folk later this month in Great Barrington edition. [When originally published, this letter began with comments about the invasion of Ukraine, which had just taken place.]

The Autobiography of W. E. B. Du Bois: Great Barrington Edition1 opens with these words:

I was born by a golden river and in the shadow of two great hills, five years after the Emancipation Proclamation which began the freeing of American Negro Slaves.

The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois’s early blockbuster, also opens in Great Barrington, with a story of Du Bois’s first experience of what he called “the veil” between the races that took place in a wooden schoolhouse that stood across Main Street from Great Barrington Town Hall.

In front of that Town Hall today stands a memorial erected in 1876, when Du Bois was eight years old, to those who fought in the Civil War, with a flying angel on top and the words, “Freedom and Union.”

You’ll find much more about the Great Barrington Editions at Berkshire Publishing. The books can be preordered now and will be shipped later this month.

W. E. B. Du Bois extolls the USSR and Communist China in the Autobiography, especially in the essays that were prominently placed at the beginning of previous editions of the book. I had toyed with the idea of taking out these chapters, which one critic said read like they’d just rolled off a mimeograph machine, but after reading them along with an accompanying statement about his Communist beliefs, I realize that Du Bois was a utopian thinker when it came to Communism. This makes them especially interesting to consider as we watch the unfolding situation between the Russian Federation, Ukraine, and the world’s uniting liberal democracies.

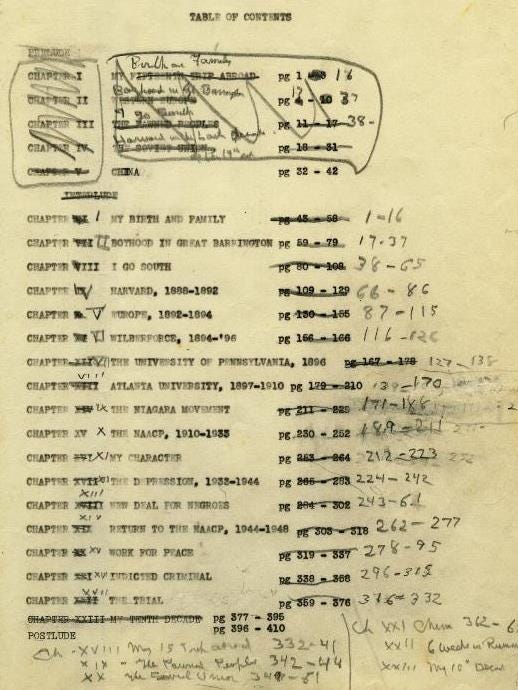

I was gobsmacked2 when I opened the document you see above. The full story of my discovery will be included in our edition, and is available below.

From Chapter 21: The Soviet Union

Here are a few extracts from the chapter, comparing Czarist Russia with the Communist system:

Her government had long been shot through with dishonesty and graft under dissolute nobles and fawning lackeys. Her punishment of crime and independent thought had long affronted the civilized world. Yet the best people of Europe and America seldom raised a finger of protest, but fawned on Russian royalty and aristocracy, receiving them with open arms. . . .

. . . they sit and sit and talk and talk, and vote and vote; if this is all a mirage, it is a perfect one. They believe it as I used to believe in the Spring Town Meeting in my village. There is power rivalry and personal jealousy; all things in the Soviet Union are not perfect. Mails miscarry, cables come a day late, styles are often queer; the world problem of domestic service has not been settled. The question of life careers and the decision between what one wants to do and what one is fitted to do, and what efforts are needed—these matters have not yet found final answers; but they are being frankly faced, and experiments are making. . . .

Is it possible to conduct a great modern government without autocratic leadership of the rich? The answer is: this is exactly what the Soviet Union is doing today. But can she continue to do this?

In fact, Du Bois’s writing about Communism is utopian in tone. He was looking for a better world, a better system, and late in life he had become discouraged by what was happening in the United States. In the 1950s he was treated horribly by the US government. He had faced indignities all his life, even as a highly accomplished and well-known Black man. The story of his being interviewed for a teaching job and then sent to the kitchen to eat, while the white candidate was invited to the dining room for dinner, haunts me. Du Bois actually took the stage for a debate with an avowed racist, someone like Nicholas Fuentes, in Chicago (thanks to Catherine Zhou for this link).

Du Bois traveled the world, visited Russia four times, and went to China to meet Mao Zedong. He died in Ghana, disenchanted with his own country. Yet his love for Great Barrington never wavered. And last month his only grandchild was buried here in the Mahaiwe Cemetery, next to her mother, uncle, and grandmother, Du Bois’s first wife and two children.

I first thought of publishing a book by Du Bois last year on the day of Black Lives Matter events across the United States, as I saw people pouring into Great Barrington for a rally at Town Hall.

I had been hearing his story for years, at events and over the dinner table, and we published a volume based on his teenage writings about the little church in Great Barrington that Du Bois had written about as a teenager. I assumed that the familiar line, “I was born by a golden river in the shadow of two great hills,” was how his autobiography opened.

But to my surprise and dismay, that perfect opening line did not appear until Chapter 6. Instead, the book opens with short chapters about his travels and Communist beliefs at the end of his life. How strange, I thought. I knew Du Bois had been a prolific writer and that he had been active in the world, occupied with political activities, editing, and organizing. Many of his books, including his groundbreaking 1903 The Souls of Black Folk, were put together in haste, compiled from pieces of journalism.

But he was also a graceful and poetic writer. I found myself doubting that this sequence was what he intended.

Looking at a more recent edition from Oxford University Press, I noticed a footnote in the excellent introduction by Werner Sollers, a Harvard historian that spoke to this question. He explained that Du Bois’s friend Truman Nelson had claimed that the original manuscript, which he had a carbon copy of, did not include those five opening chapters: "It would be interesting to compare the Nelson manuscript with the version of the book that is in the Du Bois Papers and that is reprinted here."

The story of my quest will be in the book itself, and is available here for paid subscribers. The books can be ordered now at a prepublication discount and will be shipped later this month.

Discovery - continued/…

I wrote to Professor Sollers, who encouraged me to see if I could find correspondence between Du Bois and Nelson in the archives at Boston University, and to check the Du Bois Papers at UMass. He too felt that the book would look and feel very different without those opening chapters, and wondered if Herbert Aptheker, the editor of the 1968, published after Du Bois’s death, might have played a role, given that Aptheker had been a dedicated Communist.

It was early in 2021 and library special collections were closed, but much of the Du Bois material at UMass had been scanned and put online. I was able to find a typescript of the book. It turned out to be a carbon copy marked up by Du Bois, just as Nelson had said.

I don’t know who prepared the typescript Du Bois marked up, or if he had originally intended those extra essays to be included. I’m hoping that a scholar will dig through the files and work this out. Aptheker made major contributions to Du Bois’s legacy by collecting his letters and editing a number of books, but I wonder if he also used Du Bois’s work, too, to promote and reinforce his own political views.

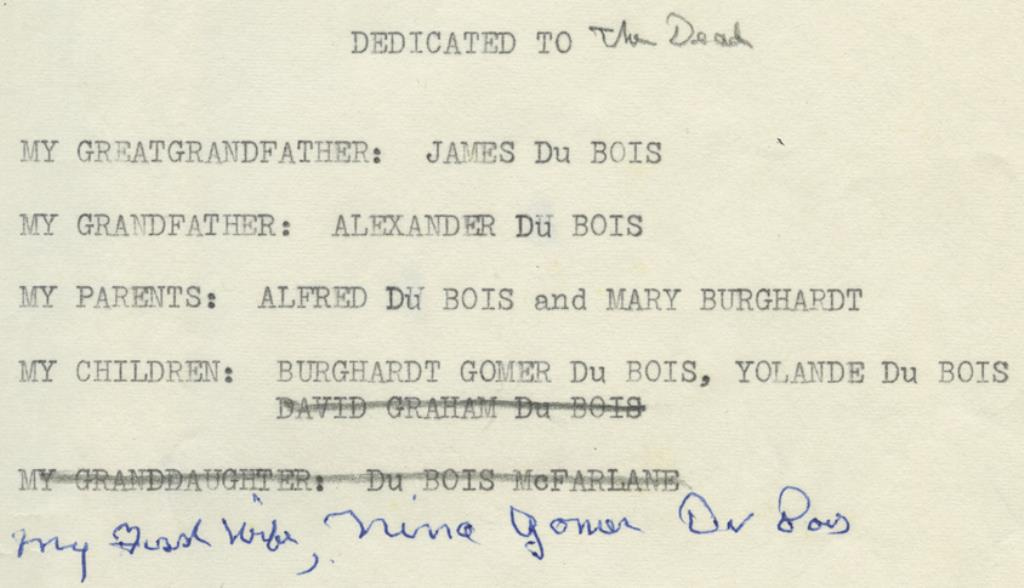

Du Bois’s reputation has been rising in recent years, and the result is different individuals and organizations vying for control of the narrative and the legacy of Du Bois. This goes back decades. When they married, Du Bois's second wife, Shirley Graham, had a 25-year-old son. The son, David Graham, took Du Bois’s name and spent the rest of his life as the main representative of his stepfather, even though Du Bois had, from his first marriage, a granddaughter of similar age as well as a great-grandson (who is still alive). I’d love to know the backstory.

Our improved version of a truly fascinating personal story is, for me, a fitting response to the local people who fought against honoring Du Bois in his hometown, not, they said, because he was Black, but because he had been a Communist. In the Autobiography, he explains why he chose to become a Communist. His reasoning, and emotion, will resonant with modern readers who share his frustration with the continued inequities in our society. While the Communism he praised did not turn out to offer the utopia he and many others hoped for, the problems he identified are still with us.

You’ll find much more about the Great Barrington Editions at Berkshire Publishing. The books can be preordered now and will be shipped later this month.

Yes, this is a bit tongue in cheek, calling it the Great Barrington Edition after there was so much fuss about the anti-vax “Great Barrington Declaration” last year. Maybe this will help wipe that from people’s memories.

Gobsmacked is one of my favorite English words! A gob is slang for a mouth (“shut yer gob”) and smacked is self-evident. But it’s the sound of the word (you have to smack your lips to say it) that makes it perfect for a surprise that leaves one speechless.

The version that went out had far too many typos but perhaps there is, as my daughter just told me, no need for apologies this week over small glitches. I'm always embarrassed by these things but, indeed, there are more important things in the world to worry about. Glory to Ukraine.