Lost in Translation

Talking about China: how translation gets in the way of understanding and cooperation

Good news this week includes the agreement to restart US-China climate talks, and I’m looking forward to Friday’s conference at Harvard’s Fairbank Center: “Co-existence 2.0: US-China Relations in a Changing World.” This the first time I’ve been to Cambridge since the day, 10 March 2020, when the governor declared a state of emergency. If you’ll be there, do let me know.

Planning for this trip was reminded me of a discussion last year about the translation of official Chinese information, how poor translation leads to mutual misunderstandings and weakens the Western position in important negotiations. It also makes ordinary news readers tune out articles about China.

One common phrase, for example, is “hurt the feelings of the Chinese people.” The background to that expression is what is known in China as the century of humiliation, when Western powers took advantage of China in a variety of ways. But modern citizens don’t know that history and even if they do they may consider it irrelevant.

No one would say that in English. In fact, to refer to one’s own success or humiliation is not considered in good taste. It would be more meaningful to express the idea as “in violation of Chinese citizens’ sense of sovereignty,” “considered offensive by the Chinese public,” or “is negatively perceived by our constituents.”

Then there are the titles of some well-known Chinese policies:

Xi Jinping Thought

Socialism with Chinese Characteristics

The Three Represents

The Four Self-confidences

The Eight Musts

None of these have any clear meaning; they aren’t really English translations. They make China seem strange and, as in the old trope, inscrutable. Not a helpful thing when people are talking about possible war over Taiwan, and, more positively, about the need for China’s cooperation on climate change.

I chose this photo from Zhangjiajie (say that one fast: roughly speaking, it’s jahng jah jeh), a national park in Hunan we visited on a whirlwind trip in 2017. Seeing these mountains, my daughter Rachel said she understood why Chinese paintings are full of amazing mountains. She’d thought they were imaginary (as you might have thought, watching Avatar, which was set in a virtual Zhangjaijie).

My son, Tom Christensen,1 first raised this issue while living in China, working in an all-Chinese department, but reading the US and UK press. Why, he asked, do US commentators refuse to learn to pronounce Chinese names? Some of them are so bad that it has to be intentional. Why does the US media continue to use childish, sing-song, and orientalist language? The orientalist angle is hard to pin down, but doesn’t it serve racist ends when the English we use in talking about China is awkward and alien?

There are various explanations for the poor translation of Chinese. One come comes down to "Chinese doesn’t have Latin or Germanic roots so of course it's going to sound awkward.” This is absurd: other Asian countries produce fine, comprehensible translations.

Another explanation is that the Chinese have been translating in volume for less time than European countries or even India and Japan, so the natural evolution of translation standards isn’t complete. But 40 years is not a short period of time, and the quality of Chinese-English AI translation is quite good - far better than official government translation.

A more realistic explanation is that this is, at least in part, the result of pride on the Chinese side. As a publisher working with Chinese partners and prospective authors, I have often been offered texts in English that are the equivalent of those policy slogans, ranging from awkward to incomprehensible.

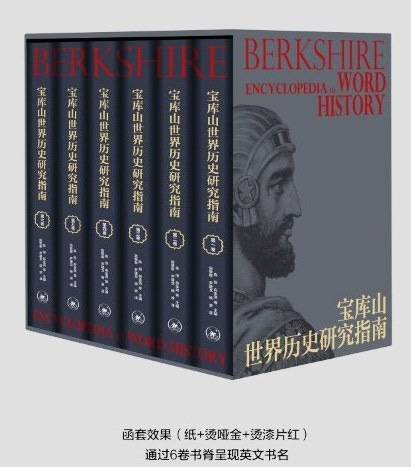

Fortunately, this image of a forthcoming translation into Chinese is a mockup! It’s usual to include the English title on a translated book in China, but a pal noticed that the English on this cover has a rather significant typo. Another colleague wrote to enquire about what seemed to be an encyclopedia of etymology. I confess that I had not noticed the error, and I’m so glad there was time to alert our colleagues in China.

When I get an email offering me a book that has already been translated, I explain that we can only publish texts in idiomatic English translated from Chinese by a native English speaker. (This is a standard in international translation, by the way, used by the UN and generally accepted within the translator community.) Some of my Chinese colleagues resist this idea, insisting that only they can understand what the Chinese means and thus are more capable of expressing it in English. Changing the text, or agreeing that a native English speaker might do a better job, would mean a loss of face.

Native Chinese people living outside China have argued that they are so familiar with English (or another western language) now that they are just as competent as a native speaker. I can understand that they would want to think of themselves as truly bilingual, and of course they often produce fine texts of their own.

Academics can be trapped by their ideas about precision, just as they often find it hard to give up the jargon terminology of a particular field and recast an idea in ordinary English (also a kind of translation). Poetry is sometimes a better model because when you translate poetry, your goal is to convey essence and well as substance, to find a way to have the same effect on the reader as the original text has on a reader of the original language. Think of how few major writers have ever successfully written in a language they did not grow up speaking. Joseph Conrad, the Polish novelist who wrote in English, was often mentioned as a unique case when I was an undergraduate.2

A more cynical explanation is that the Chinese government actually wants to obscure its policies and intentions. In any case, Chinese officials, international diplomats, and people in the academic world seem to be so used to the bizarre linguistic formulations that they are surprised when I point out that “The Three Represents” is not English, or meaningful. Something a bit more accurate would be the three constituencies, but no doubt that could be improved on.

Instead of Mao Zedong or Xi Jinping Thought, how about the philosophy of President Xi or the leadership principles of Mao Zedong? Instead of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics, why not simply say Chinese socialism?

Another one is The Eight Musts, a policy set by the General Secretary Xi Jinping administration regarding the role of the Communist Party of China. How about renaming it the eight responsibilities, the eight mandates, or the eight guiding principles of the CCP?

The translation of the “musts” themselves could do with a good deal of improvement. Must #1, for example, is translated as “We must persist in the dominant role of the people.” Say what?

The Eight Musts is a useful example in another way because the English word must has several meanings, including one we know best from the related word musty (mildewed or stuffy). Must is also the pulp and skins of crushed grapes before and during fermentation. And to muster means to assemble troops; to pass muster means to win approval. Myself, I’d use something else if I were translating this.

Planning this letter, I found something I wrote in 2014 called “No Adverbs, Please, Mr. Xi.” Here’s a bit:

There will be platitudes from both US and Chinese speakers, but I have one quiet hope: that we can get through the next week without hearing the lumpish English translation of Chinese slogans. I don’t want to hear about Xi’s “Four Comprehensives,” which are even worse in English than JIANG Zemin’s “Three Represents.” … “The strategy includes comprehensively building a moderately prosperous society, comprehensively deepening reform, comprehensively governing the nation according to law and comprehensively strictly governing the Party.”

These slogans are, to a literate English speaker, like fingernails across a chalkboard. The expression above, with its double adverbs, is the worst yet. Adverbs ruin prose, and destroy speeches. Stephen King put it best, “The road to hell is paved with adverbs.” I regret that in the Berkshire Manual of Style for International Publishing I did not emphasize this point for non-native writers of English. (Translators take note.) It's simple: cut the adverbs. When you're editing, press delete. Never look back.

I’ve had quite a debate in the Sinologists group on Facebook about translation. The “hurts the feelings of the Chinese people” sentiment came up: my observations about the terrible book translations I’ve seen (books in English prepared by Chinese presses, that is) were taken as an insult by some of the group members. The discussion raised some useful points, especially about different types of material (a scientific paper is very different from a narrative work or a poem) and about the economics of translation (what can we afford to do, and is there a “good enough” standard to apply?).

But to stick to the question of political understanding, I would like to see the US and its allies collaborate on better translations of official documents so policy makers, reporters, and business leaders who aren’t China specialists will have access to information in terms they can make sense of, instead of the stilted status quo of the Three Represents and the Eight Musts.

Of course there will be times when we need to work on explaining our English usages, too. For example, I’ve tried to explain to Chinese colleagues our different terms for the biggest shared challenge of our time. Climate change, global warming, and the greenhouse effect are different ways of saying the same thing, and there are politics involved in our current default usage, climate change. When we used to say global warming, the deniers would immediate start talking about a snowstorm somewhere that proved it wasn’t warming.

Finally, I’d like to recommend a new book by one of the speakers at tomorrow’s “Co-existence 2.0,” Susan Shirk of UC San Diego, Overreach: How China Derailed Its Peaceful Rise. It has a lot of fascinating details and is quite accessible even if you’re not a China hand. It’s also remarkably up to date, as it includes the events of this year, and provides great insight into the changes of the past decade or so.

This photo of Lake Mansfield - our Walden Pond - was taken by a neighbor, Elwood Smith, who is a well-known illustrator and a self-proclaimed beer snob. I intend to get some beer lessons this winter as part of my research on third places.

There is, incidentally, another Tom Christensen, or Thomas J. Christensen, an eminent US political scientist at Columbia University. We’re friends but not relations. You might like to read his "No New Cold War: Why US-China Strategic Competition will not be like the US-Soviet Cold War."

I actually translated two of my own books from English English into American English, the latest being The Armchair Environmentalist, but even there I was translating into my native language. My children insisted on reading only the English editions of the Harry Potter books.

In my view, the PRC party-state's officially mandated wordings or formulations (提法) such as "Gang of Four" 四人幫, "Three Represents" 三個代表, and "Strike Hard" 嚴打 are largely responsible for whatever exotic flavor some foreigners might perceive from such "party-speak." Moreover, up through the 1980s the PRC government was more honest and less misleading in its official English translations of such formal titles as "State Chairman" 國家主席 for the official head of state. (State Chairperson would be less gendered, but the fact remains that in the history of the CCP and PRC no woman has yet made it into the all-important Standing Committee 常委 that is essentially a black box and makes all its important decisions behind closed doors.) It was only during the 1990s and subsequent decades that this title 國家主席 was misleadingly translated by PRC media as *"President"; "president" is actually 總統 in Chinese and refers to an official who is directly elected in a genuinely free and fair election, such as Lee Teng-hui, Chen Shuibian, Ma Yingjeou, and Tsai Yingwen in Taiwan. So I am actually opposed to referring to State Chairman Xi Jinping (or General Secretary Xi Jinping 習近平總書記, his other genuine title,) as *"President Xi Jinping," as if he were a popularly elected head of state rather than the autocratic strongman in a single-party Leninist authoritarian regime that he actually is. However awful most of Mao Zedong's policies were, especially during the Great Leap Famine and and the Cultural Revolution, at least Mao Zedong was honest enough to refer to himself as "Chairman Mao" instead of "President Mao." PRC heads of state after Deng Xiaoping have been far less honest in this regard.