Our longest march (with photos from the Shanghai launch)

It took a full Chinese 12-year cycle to publish the translated Encyclopedia of World History

“Next time we come to China,” said my 15-year-old son Tom as we walked through a market on a spring afternoon in 2001.

My heart lifted. I’d worried that it had been a mistake to plunge him and his sister into an unknown part of the world in my typical deep-dive, all-in style.

Everyone had said, "It'll be so educational for the children." But that hardly conveys the mind-expanding experience we had that spring, in China, Kazakhstan, and Japan. The benefits weren’t primarily in having seen the terra-cotta soldiers or the Great Wall or even the caves at Dunhuang. It was the questions that flowed naturally: “What are tariffs?” “What form of government does Japan have?” “What’s the relationship between the Kazakh and Russian languages?” “Which came first, the Roman or Cyrillic alphabet?”

Even today my daughter says that first wild taxi ride across Tiananmen Square, led by a new Chinese friend who insisted we go out for a grand Peking duck meal, is one of her best memories. (The full story is here.)

As the trip drew to a close, the kids protested. Home would be boring. Everyone talking in English. No bicycles on the sidewalk. No dumplings for breakfast. But there would be the next time we come to China. “We’ll speak some Mandarin." "We’ll know about hiring taxi drivers." "We’ll stay for longer."

Indeed, Tom did become a Mandarin speaker and spent a decade in Beijing after college. And only a few weeks ago one of Tom’s projects came to fruition in Shanghai and reminded us that our long association with China - Tom’s, mine, and Berkshire Publishing’s - is not over.

That association began in Manhattan, in the offices of Oxford University Press on Park Avenue. The meeting was winding down, and the editor, in a desultory way, asked if we had any other ideas.

“How about Asia?” I blurted.

Everyone in the room stared. I had no obvious knowledge of Asia, or connection with it. But what could the editor say except that well, yes, Asia was big, and would be bigger, and indeed there hadn’t been a major reference work about it for a long time.

Our proposal went to Oxford and to Charles Scribner’s Sons. Scribner’s responded first, and before I opened the email I said to myself that their offer had to be enough money to take the kids to Asia. And it was, though we didn’t actually set off until the project was well underway and we had people to meet when we got there.

By the time Tom graduated from Grinnell College, China was hosting the Olympics and all kinds of opportunities were opening up for Western companies in China. He was happy to go to Beijing to see what he could do there as what Bill McNeill referred to as Berkshire Publishing’s plenipotentiary.

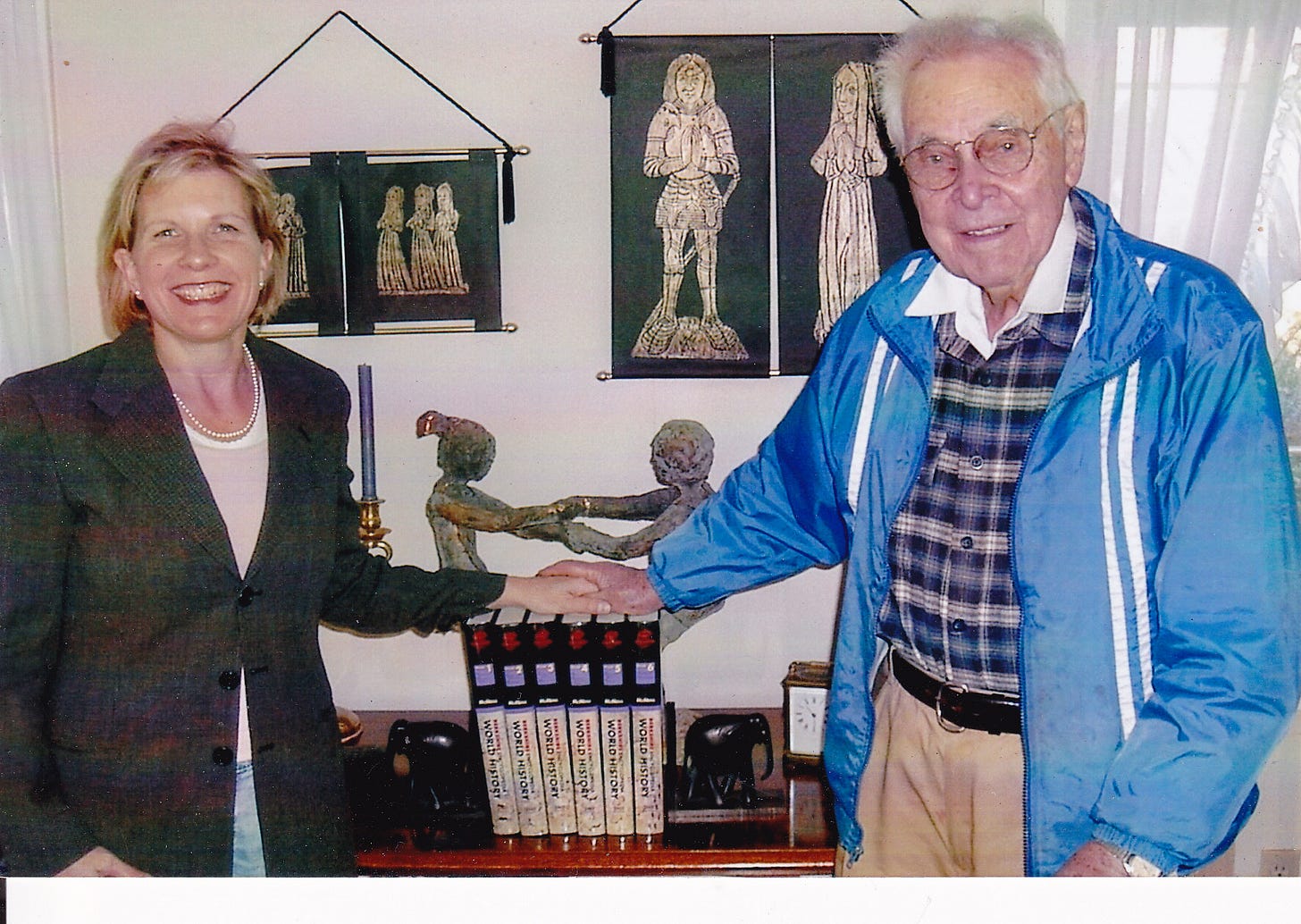

Bill (William H.) McNeill had become a collaborator and a dear friend, having retired from the University of Chicago to a village only half an hour’s drive from Great Barrington. He was one of the most important and famous historians of the twentieth century, known for groundbreaking and award-winning books that changed how scholars, medical researchers, and general readers see the world. He is sometimes called the “grandfather” of the entire field of world history because in his early books he placed a new emphasis on thinking about the past not as national narratives but as a human history – a history of all human meanings.

Many of his books had long been available in Chinese, and Tom went to work trying to sell translation rights to the Berkshire Encyclopedia of World History.

I had no idea what a long-shot that was. Encyclopedias are huge, and therefore expensive and challenging translation projects. In fact, only two major English-language reference works had been translated into Chinese: the Encyclopedia Britannica (from a company founded in 1768) and Science and Civilization in China, published by Cambridge University Press (founded by Henry VIII in 1534).

But Berkshire’s goal from the beginning was to be “a global point of reference.” Our authors came from around the world, and we were rigorous in expecting a global perspective from them. I hoped this would give us an advantage in China.

And it did. After many meetings (and some meals, I’m sure), Tom licensed both the Encyclopedia of Sustainability and the Encyclopedia of World History - each of them 6 volumes and containing over 1.5 million words - to major publishers based in Shanghai. It perhaps helped that the World History Association had held its annual meeting in Beijing in 2011, and I had spoken on Bill’s behalf to open a lecture in his name. I found an email Tom sent in November 2013:

I am heading down to Shanghai tomorrow afternoon, my time, leaving at 4pm, arriving 9pm. Staying at the Captain’s Hostel on the Bund. The next day I have a meeting with SHJT at 10am, and a meeting with Sanlian1 at 3pm. They are the purchasers of Sustain, and WH2, respectively. After my meeting with Sanlian, I take a 7pm train to Beijing, which is an overnight sleeper. It arrives at 7:30am. I would have taken sleepers both ways, but this way I get pictures of the high speed, get some experience with it, and a shower the day before my meetings.

Bill had had limited sources available to him when writing The Rise of the West, winner of the National Book Award in 1964, but he was well aware of China’s importance. His interest in China grew over the decades. His Plagues and Peoples includes an appendix on pandemics in China, in fact, the work of one of his graduate students. My involvement with China meant that we talked about China often over our weekly suppers. He wrote a long essay about “China in World History” for our Encyclopedia of China.

One evening I made Chinese dishes and brought chopsticks. Bill was game to try them, even at 96! And we managed to get on Skype with Tom in Beijing, an experience Bill found most peculiar, before he died, at age 98, in July 2016.

I knew that even if the encyclopedia had been published in the original 48 months Bill might not be alive to see and hold it, so I asked him to write a preface to the Chinese edition, a letter to Chinese readers.

Over the next couple of years we saw the relationship between the US and China deteriorate - a factor that I assumed would impact a translation project of this scale. World history is a tricky subject, as we learned when another world historian, Patrick Manning, brought a book to us, edited in Japan and written by scholars in many Asian countries. We published World History Teaching in Asia in 2019. Then came the pandemic.

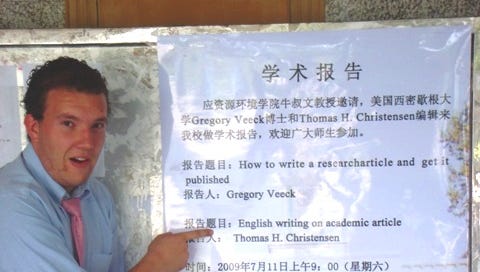

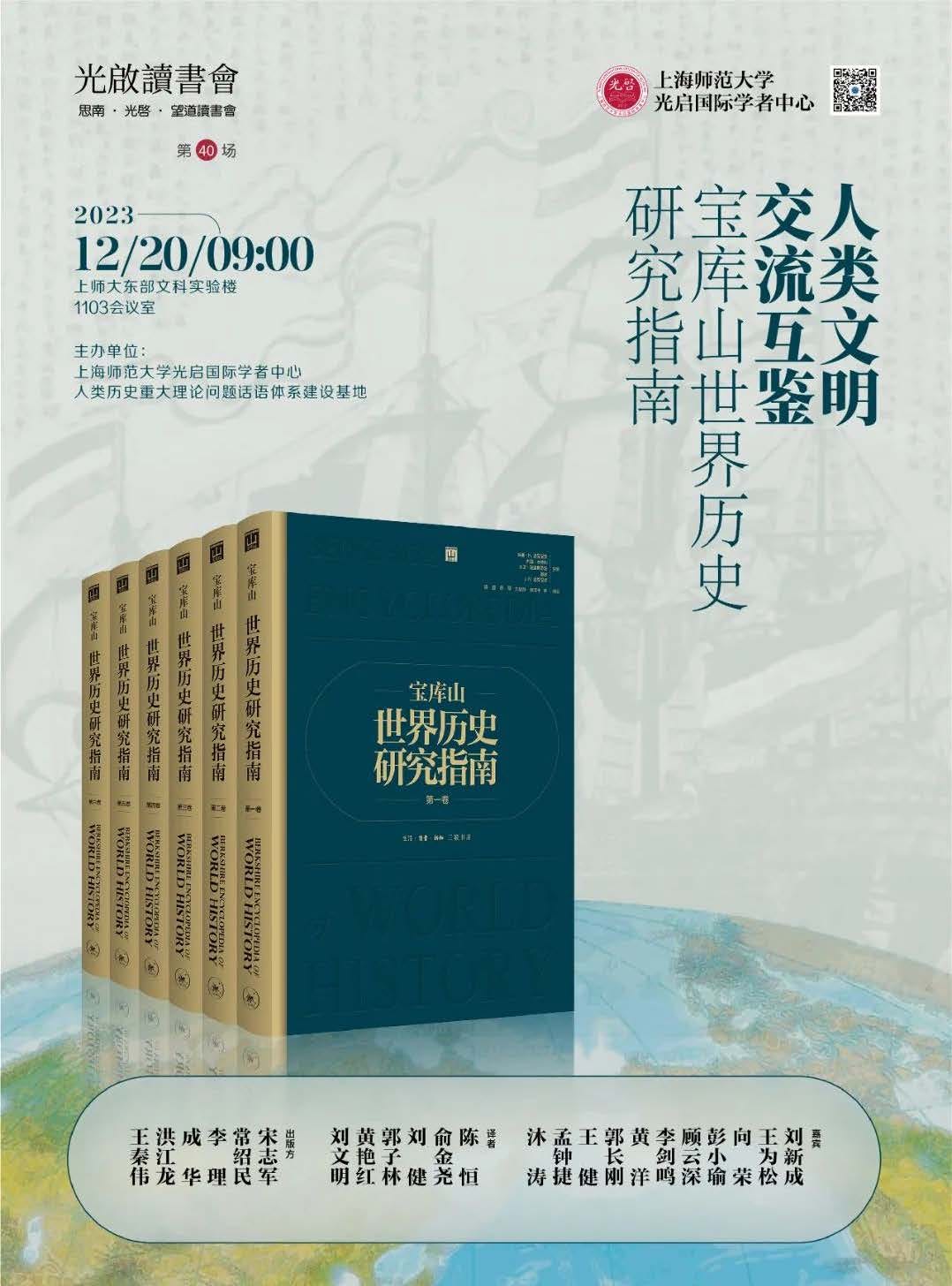

But I kept hearing from the editor-in-chief that the project was on track, and on December 20, 2023, the conference "Exchanges and Mutual Learning of Human Civilizations: Baokushan World History Research Guide" was held in Shanghai, with a room full of world history experts and scholars from Peking University, Fudan University, Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, East China Normal University, and Shanghai Normal University.

We haven’t seen the books themselves yet, and I have not seen the translation, though of course it was reviewed for sensitive political topics. I expect to have print copies at some point soon and will then hope to have some of the chapters reviewed. In the meantime, I’m delighted by the commentary of the speakers at the launch conference held on December 20th in Shanghai, which I have read thanks to Google Translate.2 (Incidentally, such an event is not a usual thing for a publication. It’s a sign of how this work is valued.) He and I worked very closely on the second expanded and very much improved edition that Sanlian used to make their translation. I feel certain that Bill, too, would be happy to have a work he labored over given this scrutiny by dozens of Chinese historians.

The conference summary is uplifting. World history has often been taught as peripheral - as a story of the other, rather than as a connected, global, human story. The British do this, we Americans do it, and no doubt the French do it, too. The excitement over the Berkshire Encyclopedia of World History echoes our intention in creating it. As Bill once commented, as we said good-bye on his doorstep, “We’ll show people that the world really is round.

Of course the news from China isn’t what we hoped for when Tom first went to China, or when we signed the translation agreement in 2012. But this publication gives me hope for better times, and for a return not just to China itself but to renewed cooperation and interaction. I miss being there, and miss working with Chinese colleagues. Even reading this discouraging dispatch from James Palmer, the Foreign Policy China Brief, brought back the time I met Christina Larson, a journalist now married to James Palmer, at a many-storied restaurant near Tom’s hutong and across from the Lama Temple - our hangout for a time.

Links to the Chinese articles about the launch conference are below,3 and I’ve uploaded PDFs of the AI-translated press release and conference summary for and our archives. I also pulled a few quotes, thinking of what Bill would most like to see:

Chang Shaomin, deputy editor-in-chief of Beijing Sanlian Bookstore, emphasized the book's macroscopic vision and easy-to-understand features, especially the content on international trade in Volume 6. He also pointed out the importance of historical theory, calling for a return to the essence of history and paying attention to major themes such as human destiny and military affairs to highlight the core value of history.

Professor Peng Xiaoyu from the Department of History at Peking University emphasized the teaching value of this book and … pointed out that the uniqueness of the arrangement of this book involves both It provides cutting-edge knowledge and can be used as a general reader for the public. In addition, Professor Peng emphasized how moved he was by the values of this book.

Professor Xiang Rong from the Department of History at Fudan University, commented on the academic contribution of McNeill, the editor-in-chief of the original English version, and its impact on global historical research, emphasizing the cross-cultural perspective of the book, which not only explores human history, but also includes natural and material history and embodies the grand view of history, demonstrates the cutting-edge of global history or new world history research, promotes China's development in the field of world history research, and expresses gratitude and respect for the translators' work.

Professor Su Zhiliang from the History Department of Shanghai Normal University emphasized the importance of the development of the world history discipline. He pointed out that the subject has made significant progress in China in recent years, and believed that the publication of this set of books is crucial to promoting the formation and practice of a global perspective.

The sample article included in the promotional material and headlined "Wonderful reading" is the piece on "Time, Conceptions of" by Bruce Warrington, an Australian contributor. I uploaded a PDF of the original so you can get a sense of the range of the Encyclopedia of World History.

We were also sent an article published in The Paper that leads with the story of Berkshire Publishing’s Chinese name, Baokushan, and even mentions our 2009 Encyclopedia of China.

"Baokushan World History Research Guide" (six volumes), edited by William H. McNeill and others, translated by Chen Heng, Yu Jinyao, Liu Jian, Guo Zilin, Huang Yanhong, and Liu Wenming, January 2024, 1980RMB

The name "Treasure Hill" [Baokushan] comes from the English name "Berkshire" of Berkshire Publishing Company. When the publishing company was preparing to publish an encyclopedia about China, it consulted its Chinese colleagues about a suitable translation for the company. Because its company is located near the Berkshire Mountains and the company is well-known in the academic community for publishing encyclopedias, it was named "Treasure Mountain" which is rich in meaning in the Chinese context.

I will light a candle for Bill McNeill when our copies arrive. And I’ll save one of the sets for Tom (who says there isn’t room in his flat in Seattle) as a reminder of the days when he was, as he put it, an encyclopedia salesman in China.

About the Chinese publisher: SDX Joint Publishing Shanghai Co. Ltd.: Shenghuo-Dushu-Xinzhi Joint Publishing Company ("SDX") was originally Life Bookstore (Shenghuo Shudian), Reading Publishing (Dushu Chubanshe) and New Knowledge Bookstore (Xinzhi Shudian), founded by Zou Taofen, Li Gongpu, Qian Junrui and others in the 1930s. The company published progressive books and periodicals, disseminating scientific knowledge and advancing national liberation and democratic movements. In 1948, the three publishers established SDX Joint Publishing Company in Hong Kong. SDX has grown rapidly since the time of reform and opening, and in 1979, launched the influential journal Reading Monthly , the spiritual home of Chinese intellectuals. In 1986, SDX Joint Publishing Company became a publishing house concentrating on the social sciences and humanities. Its publications include philosophy, politics, history, economy, literature, art and reference books. In 2002, SDX became a member of China Publishing Group with a mission to "serve the readers wholeheartedly" and offer "humanitarianism and wisdom."

AI translation won’t do for a book, but it is very useful indeed for someone like me, navigating a lot of text in a language I don’t read. I recently signed a translation contract with Japan that specifically guaranteed that they would not use machine translation.

There's a latest review from The Paper: https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_26019135

And the press release and launch summary in Chinese: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/x6bMI42sLps9oZ3AlTFQTg / https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/LnwDWT_t7Ndx6VlG65l0fQ

Congratulations to you, Karen, and the entire Berkshire team.

You "took whole" a wonderful project on human history. (Sun Tzu)

保持良好的工作 宝藏山

Bǎochí liánghǎo de gōngzuò Bǎozàng shān

Here's Bill McNeill explaining how his professors taught about China, and how he came to a new way of understanding the human past. https://youtu.be/xo84LXpRD1I