Public bathhouses—from saunas and geothermal baths to the neighborhood sentō in Japan—have often been third places. In Iceland, public baths are a part of life today.1 These baths come in many shapes and sizes, and each has its own set of traditions and rituals, but each type is a gathering place where we take our clothes off and tend to our bodies with water and heat. This invariably means relaxation and a release of responsibilities.

They also tend to be social. Nakedness itself does much of the “leveling” required by a third place. The Japanese call it hadaka no tsukiai— “naked bonding.”

Nonetheless, I was doubtful that private saunas—that is, saunas and steam rooms in clubs and gyms—could be third places. They are not open to all and thus not diverse in the way a pub (public house) is. But as I became a regular at the Simon’s Rock College sauna I began to understand that that small wood-panelled room, installed 5 years ago at poolside, has many of the characteristics of a third place.

Perhaps the most important is the idea of regulars, who pick up conversations from one meeting to the next. Yesterday a certain fellow came in, looked around, and said, “The gang’s all here!” That’s a clear marker for a third place.

The discussion of golfers and golfing somehow shifted to the question of trans athletes. We talked about different sports—from football to fencing—and the physical advantages men have in terms of height and muscle. I told them about the women I’d worked with on the International Encyclopedia of Women and Sports and how hard it was for women athletes to get attention and support throughout the 20th century. (One of them was Mariah Burton Nelson, an athlete and journalist, who now writes a newsletter called Stronger Women. Her latest post is “I Reached Out to a "Middle-Aged Trans Woman" to Discuss Women and Sport. Here's How It Went.” If you’re concerned, as I am, about finding common ground and breaking down political polarization, I think you’ll enjoy it.)

In the sauna, the conversation veered to gender in general. The late-coming fellow, whom I’ll call Hans, went on a tear. “What ever happened to femininity?” he said. “Women don’t want to mow the lawn or fix cars. They hate going out to work, it’s the breakup of the nuclear family. Look around you. The women, they hate being secretaries and commuting three hours a day and that’s what most women do, they’re just secretaries.”

As you can probably imagine, I was shaking my head and laughing throughout this tirade. But you might be surprised that it did not make me angry. Here’s why: we’ve had other conversations, many of them agreeable.

When I first met him before the November election, he often started lecturing us on geopolitics. Eventually he recognized that I knew a thing or two about international issues and he shut up about politics. Over time, we’ve talked about languages, trains, artwork, and fixer-upper houses. We’ve talked, all of us, about the future of our beloved athletic center. (The closure of the college was announced by the provost in November).

Overlapping ties have long been shown to reduce conflict. We may disagree about funding a new school building but agree about other local issues, and if we have enough opportunities to connect, to see people in action and get a measure of their character, we’re much less likely to lose our cool about a single issue. And less likely to believe that we are utterly and forever polarized.

Hans is, after all, not the only man with a tendency to mansplain. I am frequently the only woman in the sauna group, which means that I sometimes have to hammer my way into what should be give and take. There are times when conversation is no sport for the weak!

Do you find that it’s harder to find conversational give and take, and that people are less likely to ask questions? Here’s an article from The Guardian about the non-askers.

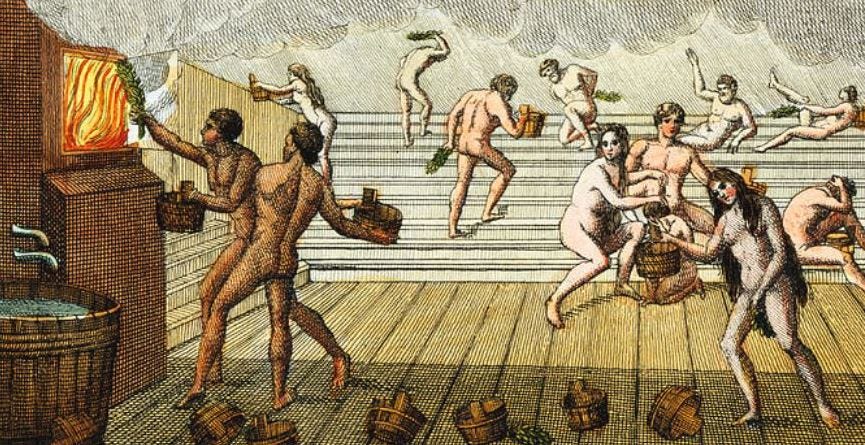

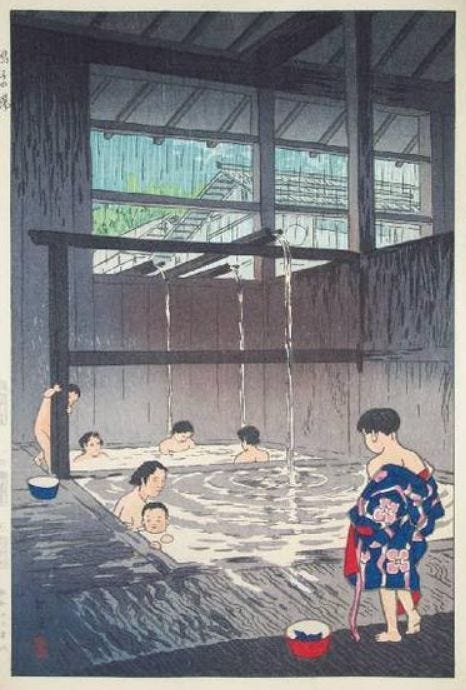

I assumed that most communal bathing was divided into men and women, but from the old illustrations I’ve included that seems not necessarily to be the case.2

The sauna, like all third places, makes for overlapping connections. A man passed me at Annual Town Meeting on Saturday and said, “Hey, hi there, I almost didn’t recognize you without a towel.” We may well have voted differently on some issues, but that wouldn’t matter next time we met.

And I’m glad we aren’t entirely homogeneous, and that we have enough trust, and familiarity, that Hans can say his piece about femininity. Maybe next time I’ll share a few thoughts on masculinity. While I’ve seen him shut down by a woman—who said she didn’t want to hear politics in the sauna—I’ve never seen hostility.

For another vantage point, I’m planning to visit Wander, a new cafe and event venue in Pittsfield, the old industrial city at the center of Berkshire County. “That’s a third place,” someone told me.

Reading the Wander website, I learned that “Wander is a community gathering space in the heart of Downtown Pittsfield. Come, step into our light filled space, where all are welcome.” I could see the sauna bros going for beverages that “promote well-being and vitality.” But when I saw, “As a queer and transgender-founded business, we are deeply committed to creating a space where everyone feels seen, heard, and valued,” I found myself wondering if that being seen and heard and valued would include Hans. Or me, for that matter. I'll try to find out.

Thinking of gender in terms of leadership, I was intrigued by a passage in Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging, a small book by Sebastian Junger, author of the bestseller The Perfect Storm. Junger tells the story of a mining disaster and how leadership roles changed amongst the miners trapped 2 miles below the surface while they waited for rescue.

Without exception, men who were leaders during one period were almost completely inactive during the other; no one, it seemed, was suited to both roles. These two kinds of leaders more or Jess correspond to the male and female roles that emerge spontaneously in open society during catastrophes such as earthquakes or the Blitz. They reflect an ancient duality that is masked by the ease and safety of modern life but that becomes immediately apparent when disasters strike. If women aren't present to provide the empathic leadership that every group needs, certain men will do it. If men aren't present to take immediate action in an emergency, women will step in….

To some degree the sexes are interchangeable—meaning they can easily be substituted for one another—but gender roles aren't. Both are necessary for the healthy functioning of society, and those roles will always be filled regardless of whether both sexes are available to do it.

The coming-together that societies often experience during catastrophes is usually temporary, but sometimes the effect can last years or even decades. British historians have linked the hardships of the Blitz—and the social unity that followed—to a landslide vote that brought the Labour Party into power in 1945 and eventually gave the United Kingdom national health care and a strong welfare state. The Blitz hit after years of poverty in England, and both experiences served to bind the society together in ways that rejected the primacy of business interests over the welfare of the people. That era didn't end until the wartime generation started to fade out and Margaret Thatcher was elected prime minister in 1979.

"In every upheaval we rediscover humanity and regain freedoms," one sociologist wrote about England's reaction to the war. "We relearn some old truths about the connection between happiness, unselfishness, and the simplification of living."

What catastrophes seem to do—sometimes in the span of a few minutes—is turn back the clock on ten thousand years of social evolution. Self-interest gets subsumed into group interest because there is no survival outside group survival, and that creates a social bond that many people sorely miss.

Twenty years after the end of the siege of Sarajevo, I returned to find people talking a little sheepishly about how much they longed for those days. More precisely, they longed for who they'd been back then. Even my taxi driver on the ride from the airport told me that during the war, he'd been in a special unit that slipped through the enemy lines to help other besieged enclaves. "And now look at me," he said, dismissing the dashboard with a wave of his hand.

Junger’s account leaves me wondering about how we can blend a hard-edged, populist leadership (which provides a sense of tribal belonging) with the empathetic leadership we need, too. And whether our online activism has left us without the sense of solidarity that people so often find in troubled times.

I’ll be watching how the new prime minister of Canada, Mark Carney, handles his meeting today with the US president. Janan Ganesh wrote in the Financial Times this week that “The next wave of winning liberals will act more like Carney than a conciliator like Clinton.”

I cannot resist including this comic skit about Icelandic shower wardens, which reminds me of the posters in a locker room at a public pool in Copenhagen, giving detailed instructions on thoroughly washing every body part before entering the pool. I think we could use similar instruction at Simon’s Rock.

A few articles on public bathing I found particularly interesting, with some wonderful illustrations:

Typology: Bathhouse from the Architectural Review

One of the regrets of my trip to Kyoto was not making a trip to an onsen. The closest I got was cold soaking in my hotel room’s ofuro tub after walking around the city.