Whose life is it, anyway?

Biographers, memoirists, family, friends, lovers, and lawyers weigh in.

My mother had given me permission to write about her going back to college, but after reading my letter “Never Too Late” she called and said, “You mentioned my getting pregnant!”

She was right. I mentioned that she was pregnant when she and my father married. We joke about it now. But for years that fact was supposed to be a deep dark secret.

There are darker secrets in my mother’s family that have emerged over the years, genuinely tragic events. “Didn’t anyone talk about them?” I’ve asked.

She responded, “My mother always said you don’t wash your dirty laundry in front of the neighbors.”

That’s my subject today: the details of our lives that we don’t think other people should know about. We all have a tendency to craft stories about our lives, we come to believe in our own semi-fiction, and we want to control any narrative told by others.

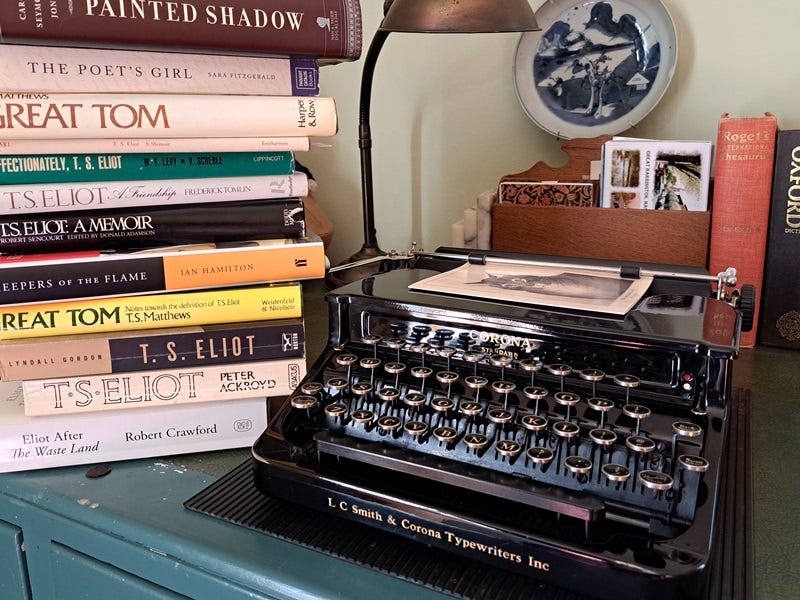

This is a major issue for biographers, memoir writers, and historians. I’m about to publish a book that puts biographers’ search through dirty laundry – or what the author T. S. Matthews referred to as a search for “where the body is buried” and “the ammunition dumps" – in the spotlight.

Writing Great Tom comprises the diary and notes of a well-known journalist and former editor of TIME, T. S. Matthews, written while he was doing the research for the first biography of the poet T. S. Eliot. Matthews kept the diary as an outlet, and a backup text in case he was unable to finish a biography because of the obstacles thrown in his path by Valerie Eliot, Faber & Faber, and libraries including the Houghton at Harvard and the Bodleian at Oxford. It includes dozens of letters to and from people ranging from Robert Lowell and Edmund Wilson, Lionel Trilling and Valerie (Mrs. T. S.) Eliot.

Matthews wrote:

The reason this project has generated so much emotion, it seems to me, is because there is a moral question concerned. What right has anybody to dig into somebody else’s life against the wishes of that person? I think most people sympathize with the quatrain in the church at Stratford which is supposed to have been written by Shakespeare: Good friend, for Jesus’ sake forbear To dig the dust enclosed here. Bless’d be the man that spares these stones And curs’d be he that moves my bones. (or something like that). We applaud and sympathize with a man, especially what we call a great man, a prominent man, who wants to keep himself private and keep his private life separate from his public life, on the grounds that it is of no concern to anyone but himself. We sympathize with that; we even applaud it. How then can there be a case for going against Eliot’s expressed wish?

But who’s life is it, anyway? Eliot’s life was woven into the lives of other people, and it turns out that it is not just biographers and scholars who want to pick over his bones (if that’s how you see it), but women whose lives became entwined with his who wanted to be seen and heard -not effaced and not silenced.

That has been, and remains, the dilemma. As I write about Valerie Eliot, I face the same resistances as Matthews did, 50 years ago. Last week I read material at the Houghton Library that the Eliot Estate apparently forgot to restrict - a small victory!

It seems absurd, doesn’t it? Eliot died in 1965, Valerie Eliot died in 2012. They had no children. Why should the administrators who now manage the “Estate” (wealthy because of Cats) demand to see, and censor, any book manuscript for which the author seeks permission to quote from Eliot?

The issue today is control over the T. S. Eliot legacy, which is closely tied to the publishing house he helped to found. But the original restrictions were the result, I now know, of Valerie Eliot’s long struggle to keep the other women in her husband’s life out of sight and out of the record.

Of course there are ethical as well as legal issues when it comes to writing about other people’s lives. And even after someone dies, there may be children or grandchildren or friends and lovers who won’t want the truth told on certain subjects, or to be included in a narrative. In China, the desire to restrict information goes much deeper, as I learned when trying to publish Chinese biographies.1

There are book-banning parents today whose major criterion is whether books have any reference to sex. Don’t miss: “This Summer, I Became the Book-Banning Monster of Iowa”:

Iowa’s “parental rights bill,” signed into law at the end of May and made effective July 1, . . . mandates that school libraries may only contain “age-appropriate” books free of any “descriptions or visual depictions of a sex act” as defined by Iowa Code. In a particularly draconian move, the law holds individual teachers and school librarians accountable for violations.

But for the most part we talk quite freely about topics that were off limits 50 years ago: alcoholism and other dependences, cancer, mental illness, sexual abuse. But it varies a good deal. If truth is likely to tarnish the reputation of a Great Man or a Great Woman, someone significant enough to have a biographer interested in them, there are likely to be people upset about it. And if the biographer takes on a living figure, heaven help them!

A standard clause in book contracts requires the author to indemnify the publisher against claims related to obscenity, breach of copyright, and defamation. Defamation is rather like obscenity: it’s in the eye of the beholder. And countries have different laws. The UK has been more restrictive than the US. I was threatened by various industry associations as well as McDonalds when Home Ecology was published. Years later, the Guardian’s lawyers kept demanding cuts from my essay about Valerie Eliot, and quite a few people thought she would sue me for writing the piece at all.

Was it wrong for me to write that Valerie only felt comfortable with working-class women? The British lawyers thought that might be considered defamatory. It would certainly have made for an amusing legal brief.

But one could also argue that Valerie, when alive, owned her own story. What right had I to write about her? And I think most people would agree that my mother owns her own story. I knew that she wouldn’t really mind if I wrote about her first pregnancy because I know how open she is. Mom’s story is also mine, isn’t it, since I’m one of the babies? Our lives are interconnected.

I’ve come to believe that telling our stories, our true stories, is a good thing. I hope that all the people writing memoirs these days will aim to reveal rather than conceal. Honest accounts are, after all, a lot more interesting. And admitting our mistakes might just be helpful to someone else.

This brings me to the story behind the photo at the top of this letter, and to another woman I knew and am writing about: Sophia Wittenberg Mumford, wife of Lewis Mumford.2 It also leads to a topic no one wants to talk about: marital infidelity.

Sophie talked freely to Lewis’s biographer, Donald Miller, while he was writing Lewis Mumford: A Life, published in 1989. Lewis himself died in 1990, but suffered from dementia for years before his death, so he wasn’t aware of the biography, or the aftermath of its publication.

Lewis had himself written several autobiographical books. (He was so well-known that his publishers let him get away with these forays when they really wanted a complete autobiography.) In them, he wrote explicitly about one of his extramarital affairs. Sophia had given her agreement and read them in draft. She became used to answering questions about Lewis’s revelations, saying that she and Lewis believed in living a life that could bear exposure.

Sophie came to trust Donald Miller and confided in him the story of Lewis’s late life-love affair with a Vermont artist, which Sophia had found devastating. He promised not to reveal that story in the book, and he didn’t. But he did write quite a lot about the early affairs.

Sophie was distraught, and furious. She told me that Miller had misinterpreted Lewis’s character and Lewis’s life, and been salacious in the details he included. I felt for her. She had become my dear friend and I loved her. I accepted the story as she told it and intended to play down the issue of infidelity when I wrote about her life.

Then I met Gerald Holton.

Gerald is a Harvard physicist who is now 101. He and his wife Nina were friends with the Mumfords until the men had a huge, public row over Gerald’s review of Mumford’s Pentagon of Power in the New York Times Book Review.3 I knew the story of the breach but it had not occurred to me that Holton might still be alive and someone I could interview. But in 2014, I discovered that the Holtons were long-time Cape Cod neighbors and Harvard friends of my friends Jerry and Joan Cohen.

“You know Gerald Holton!?” I exclaimed. Jerry Cohen, with a typical flourish, said, “I not only know him, but I can produce him.”

At the end of our first meeting, Gerald mentioned that a woman had come to talk to him about Lewis Mumford because there were some letters at Harvard. Letters from a lover, he thought. I said I didn’t think that could be true, I knew where all the Mumford letters were. But he was right and I was wrong: there was indeed a cache of letters between Lewis and the Vermont painter now in the Schlesinger Library, having been discovered in a fireproof box in an abandoned house.

What I’ve learned from these letters is that Sophie late in life suffered far more deeply over Lewis’s infidelity, both early in their marriage and later, than she had ever let on. I admire her strength and resilience and good humor, even about his love affairs, and know that she and Lewis had a remarkable bond that endured for nearly 70 years. But I cannot avoid the issue in writing her life story, even though I wonder if she would feel this as a betrayal.

But who is entirely comfortable having their own failures and weaknesses exposed? While T. S. Matthews was furious about the barriers T. S. Eliot’s widow and Faber & Faber put in his way, he was not happy about having his own love life written about, as biographer Carl Rollyson explains:

In response to my query about his marriage to Gellhorn, Matthews quoted Macbeth's lines to Banquo's ghost: "Hence, horrible shadow! Unreal mockery, hence!" So I wrote a story of the marriage based on my reading of Matthews's character and on everything I had come to know about Martha Gellhorn. I did not make up any events, but my reading of the marriage's psychological dynamic remained, for the moment, purely speculative.

If you are interested in how biography is done, I recommend Carl’s Confessions of a Serial Biographer as well as his regular biographical podcast (I’ve done a couple with him). I’m excited about his next project: a book about the writing of presidential biography. Carl is particularly good on the subject of “authorized” biographies, which still have a cachet it seems, even though being authorized almost always means being controlled by people who have a personal interest in having a life told in a certain way. (The ruptures between authorized biographers and their subjects are legend.)

Now it’s time for me to join the International T. S. Eliot Society Annual Meeting, held this year at Harvard. I’m looking forward to talking to people about Valerie Eliot and about Writing Great Tom, the diary of an unauthorized biographer that feels awfully familiar to those of us writing about women connected with Eliot more than 50 years later.

I think of my lengthy discussions with Bloomsbury and Oxford University Press about doing a Who’s Who in China. Seems obvious, doesn’t it? Look up a newly promoted official and find out where he (always he) went to university, whom he’s related to, perhaps even what his interests are. The proposal circulated for some months, and eventually I sent an enquiry to some of my Chinese colleagues. They were dumbfounded. Only then did I learn that information publicly accessible in the west (marriages, births, deaths, and property transactions) and the kind of information about public figures we find on Wikipedia (sometimes startlingly intimate) is considered confidential in China. Because guanxi - connections - are so important in Chinese business and politics, if you want to know about someone there you really need to know whom they went to school with, and worked with early in their career. I also learned how adept some wealthy Chinese families are about not using the same family name in public documents, so you really have to dig to find out that whose brother or daughter someone is. The Berkshire-Oxford Who’s Who did not get off the ground.

Sophia Wittenberg Mumford worked at The Dial magazine in the late teens and early 1920s and was married to Lewis Mumford for nearly 70 years. She died at 97 while I was working with her on a book about her life, because she urgently wanted to write a book of her own, to tell her own story.