I have avoided Sylvia Plath for years. I’ve never wanted to admit to my youthful identification with her. This was not because I wrote poetry, but because I was an ambitious student and writer who wanted a bigger world. After running away to a commune at 14 and trying out fundamentalist Christianity, at 18 I decided to take a different path, and reading about Sylvia Plath provided guideposts that I have never before acknowledged

I applied to Smith College, went to Harvard Summer School, and was offered a job at Conde Nast in New York. 1I had babies with an Englishman, and moved briefly to Devon with the little ones. I typed endless cheery letters while writing a novel set in the Silicon Valley.

Life veered in other directions. I took up with new lovers, a new career, and left Plath behind. I saw her suicide as a disappointing surrender.

But my friend in biography, Carl Rollyson, keeps writing books about Plath, after having written about women I admire, like Rebecca West and Jill Craigie. What on earth did he see in Plath?

As you’ll hear in the podcast, Carl is on a mission to get us to see Sylvia Plath differently, to tell a new story, to go beyond the myth rather than perpetuating it.2 I think you’ll find the explanation of his commitment to this project as convincing as I did - and perhaps you too will pull dusty copies of her poetry down from a shelf.

Carl, incidentally, has a similar perspective on Marilyn Monroe, whose full talents and ambition have been given short shrift.

What makes Plath great, and it's true of all great writers, is that they continue to remain relevant. Because new generations find things that those earlier generations, their own contemporaries, did not see. They didn't see in Marilyn Monroe. Her contemporaries could not have imagined that we would be still talking about her.

Plath’s story shows how women’s desire to have it all, and to be all things to those around us, can be crushing. And she really did try to do it all. As Carl and I talked about how she was getting up at four in the morning to write during that last very cold winter of 1963, I kept thinking about hard - perhaps impossible - it must have been to keep up with the nappies (old-fashioned British diapers were big squares of terrycloth, very slow to dry) in a London flat without central heating. And that was only one thing she had to deal with during those dark days.

We talked about Plath’s desire to host a salon, to bring creative people together, and how she struggled, as an American and newly single mother, to make the friends she longed for. A salon is a kind of third place, and I found that she had other third places in mind, too as she wrote this passage from her journals:

Yes, my consuming desire is to mingle with road crews, sailors and soldiers, barroom regulars—to be a part of a scene, anonymous, listening, recording—all this is spoiled by the fact that I am a girl, a female always supposedly in danger of assault and battery. My consuming interest in men and their lives is often misconstrued as a desire to seduce them, or as an invitation to intimacy. Yes, God, I want to talk to everybody as deeply as I can. I want to be able to sleep in an open field, to travel west, to walk freely at night.…

That sums up what a lot of women feel.

The ghost of Sylvia Plath

After Carl and I recorded this show, I found myself wondering Plath’s writing - which her estranged husband Ted Hughes inherited, controlled, and censored - has made more money than Hughes’s own work? It would be interesting if Faber & Faber made more from the wives of their two great poets than from the men themselves. Valerie Eliot’s success with Cats saved Faber & Faber, and Sylvia Plath, not a Faber author until after her death, has probably contributed more to the company’s bottomline than Hughes.

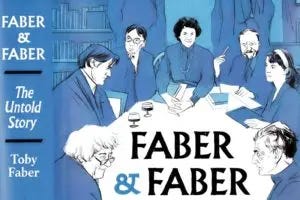

But in another twist to the Plath story, Fabers misrepresent her on the cover of a history of the press, written by Toby Faber and published in 2020. This annoyed me a great deal because Sylvia Plath was not, alive, a Faber author because they did not want her work - they wanted Ted Hughes.

Yet she is one of the two women shown on the cover of the book, sitting around the firm’s famous editorial table with P D James as well as poets Eliot, Spender, Heaney, and Hughes? The endpapers include her signature at top right, the most prominent position of all, with T. S. Eliot immediately below hers. (Marianne Moore makes the endpapers, though not the cover.) Even worse, the Plath in the cover drawing is a ghost, modeled on a 1956 wedding photo. At least Ted Hughes is not seated next to her (he’s the fellow with shaggy hair across the table). See what you think about the ghost of Sylvia Plath.

Show Notes

Carl Rollyson is a prolific biographer as well as a critic who writes and podcasts extensively about the art of biography. His next book is Making the American Presidency: How Biographers Shape History (University of Virginia Press). Read more about him here. His website is CarlRollyson.com.

Amongst Carl’s books about Plath:

The most recent and most comprehensive biography of Ted Hughes is by Jonathan Bate. Here is Carl’s review.

Previous episodes

I turned down admittance to Smith and Yale after meeting Marvin Mudrick at UCSB, and I didn’t take the job at Conde Nast because I wanted to go to London.

Other biographers are on a similar mission. “[Heather] Clark, a professor at the University of Huddersfield, in England, and the author of [Red Comet] . . . explains in her poignant and closely argued prologue, she believes that Plath’s “life has been subsumed by her afterlife” and that depictions of her as “a crazed, poetic priestess are still with us.” Read more.

Share this post