Life in public: a continuing affair

Defending democracy requires vigilance and a lot of conversation

The title The Way We Live Now suggests I should always write about present-day matters. But I’ve been steeped in history and am a devoted reader of old books, and I often come across stories and commentary that are relevant, sometimes unbearably so. Today we’re stepping back to the 1980s with brief excursions to 1831, when Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville visited the United States, and to the reign of Charles I of England.

Here’s a passage from a book Ray Oldenburg urged me to read many years ago, The Company of Strangers by Parker Palmer1, published in 1981:

When Alexis deTocqueville visited the youthful U.S.A. in the early nineteenth century, he noted that even then we were a nation of joiners. Everywhere he looked people were banding together in voluntary associations—including churches—to share common interests, to accomplish common goals, to express a common faith.

And de Tocqueville saw, with uncommon insight, that if the American experiment in democracy were to succeed, it would require the continued health of these voluntary associations, these crucial forms of public life, because democracy requires some way of defending the isolated individual against the tendency of central government to grow larger, stronger, and more domineering. Any power, even in a democratic state, wants to enlarge its domain: it gravitates toward controlling the thought and behavior of every individual in the society—an impossible goal, but one toward which power is ineluctably drawn. The individual who possesses conscience and freedom of thought and action is often anathema to the determinations of political institutions. Such folk rankle and rabble-rouse and resist in ways which make governing more difficult than those who govern might like. History offers numerous examples of power's tendency to expand its own domain, "totalitarian" societies so-called because of their success in achieving near-total control. One characteristic of every such society is the abolition of public life.

One of the questions about third places is how they relate to the membership organizations Robert Putnam, author of Bowling Alone, is so fond of. Here’s what Parker Palmer has to say, which speaks so clearly to our time (I’m giving you quite a long passage because the point he’s making is important.)

As we come to understand the centrality of voluntary associations in the public health of our society, and as we look around at the large number of such associations which dot the American landscape, it is tempting to conclude that the public life is not nearly as threadbare as I have claimed. Readers will think of instances in which people act together with vigor and discipline, when (for example) a federal judge orders school integration through busing, or when a planning agency proposes to build lowincome housing in a suburban neighborhood. Then it becomes clear that there are matters of vital interest to all—the schools, our neighborhoods, the relations of the races, the extent of the law's authority. Then, it would seem, a public life is generated.

But such outbursts of "public" activity are not deeply public at all. They may, in fact, be symptoms of how little public life we have. First, the events which arouse public interest are often events which threaten to bring diverse elements of the population into more frequent contact with each other, as through school busing or public housing. If genuine public life means anything, it means the ability to live with diversity, not ignore it or try to gerrymander it out of view. These episodes of so-called public sentiment are riddled with the fear of diversity, which itself is a symptom of our disease.

Second, events such as these occur only sporadically, while genuine public life is a continuing affair. The public life depends on regular encounters—most of them not overtly political—between strangers who cross each other's paths, become accustomed to each other's presence, and come to recognize their common claims on the society. When the balance of life shifts heavily toward the private and these regular encounters diminish, people come into public only in moments of crisis, moments which usually set stranger against stranger in sudden and unexpected conflicts of interest. There is an inverse relation between the health of public life and the need to conduct politics by crisis: the less public life there is, the more likely that conflicts will reach the crisis point before they are dealt with. A healthy public life creates a steady flow of information and opinions so that threats to one's interests are perceived and responded to gradually and in advance, thus increasing the chance that interests can be altered or accommodation reached.

Third, the way we frame these conflicts over (for example) busing and housing belies the notion that they reveal a lively public life. We define them as "zero-sum" games in which each gain for one side is a loss for the other; a game, that is, in which some must lose in order for some to win; a game where it is inconceivable that everyone might emerge with a victory of some sort. A genuine public life would begin with the premise that there are victories for the whole which are greater than a victory for any of its parts. We would understand that we are members of one another; that the social order will be secure for our own life, liberty and pursuit of happiness only if it is secure for others as well. We would know, for example, that when we force low-income housing out of our community we are not solving the problem but merely postponing the day of reckoning. Worse still, we are allowing the pressures of inequity and resentment to build to a point where no rational solution will suffice. The foundation of public life is the tenacious faith that we are in this together and can find ways for everyone to win. This is not a faith which accompanies many outbursts of so-called public activity these days.

In fact, a growing number of the voluntary associations in which de Tocqueville placed such hope reflect a loss of this public faith, the faith that we all can win. I refer, of course, to the single-issue groups which now dot the American scene, groups whose philosophies and strategies deform the public realm.

The voluntary associations which contribute most to our political health are those with broad-based concerns, those which (like the church) allow people to come together, to share opinions, to influence each other's thinking on a broad range of issues. The health of a democracy is premised on the assumption that the population will not be divided along single-issue lines; that there will be a variety of cross-cutting divisions between us; that you and I will be on the opposite side of some causes but on the same side of others; and that in this way we will come to see that we are related despite our differences.

But single-issue groups separate people along absolute lines. They take one concern and make it not only paramount but apocalyptic. If you are not against (or for) voluntary abortion; if you are not for (or against) gun control; if you are not against (or for) nuclear power; then you are among the damned. For such groups and the people who join them, the world has only one moral boundary. And with this kind of thinking the idea of a public with complex and interlaced concerns is lost. Now there can be no accommodation, no compromise, no balancing of interests, no looking beneath the conflict for a creative "third way." Buy the book here.

I remember being startled that Ray O was recommending a book with the subtitle Christians and the Renewal of America’s Public Life, but as the years have passed it seems to become more and more relevant. Ray wrote similarly about membership associations:

Free assembly does not begin with fraternal orders, reading circles, parent-teacher associations, or town halls. Those bodies are drawn from a prior habit of association nurtured in third places.

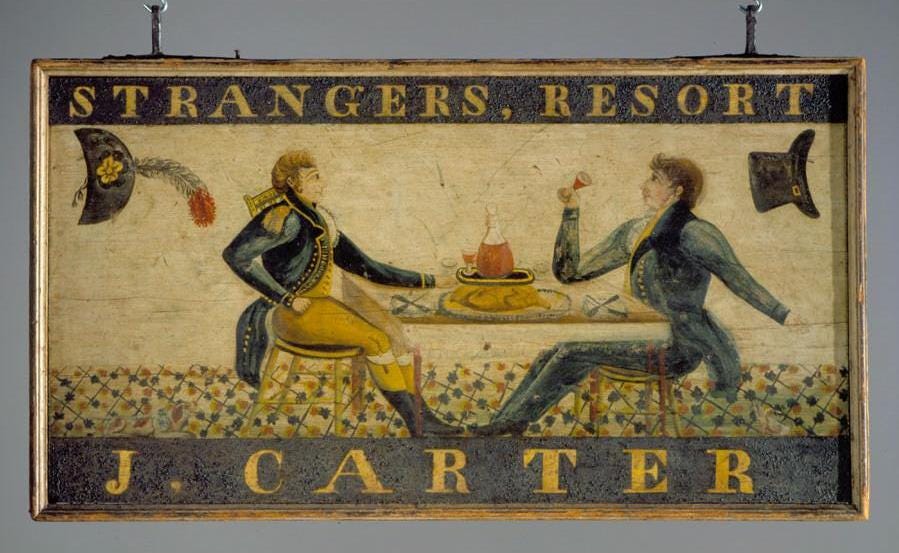

There must be places in which people can find and sort one another out across the barriers of social difference. There must be places akin to the colonial tavern visited by Alexander Hamilton, which offered, as he recorded, “a genuine social solvent with a very mixed company of different nations and religions.”

This leaves us with the question of where we —at a time when we are more diverse, by far, than those men who met in colonial taverns—can gather, talk, and organize?

Third place as “leveller”

I have been going over the much-quoted list of characteristics of third places to make the points as universal and clear as possible.2 One of them, as Ray O put it, is that third places are “levelling.” Here’s his explanation from the 1989 The Great Good Place:

Levellers was the name given to an extreme left-wing political party that emerged under Charles I of England. The goal of the party was the abolition of all differences of position or rank that existed among men. By the middle of the seventeenth century, the term came to be applied much more broadly in England, referring to anything "which reduces men to an equality." For example, the newly established coffeehouses of that period were commonly referred to as levellers, as were the people who frequented them.

A place that is a leveler is, by its nature, an inclusive place. It is accessible to the general public and does not set formal criteria of membership and exclusion. There is a tendency for individuals to select their associates, friends, and intimates from among those closest to them in social rank. Third places, however, serve to expand possibilities, whereas formal associations tend to narrow and restrict them.

Third places lay emphasis on qualities not confined to status distinctions current in the society. Within third places, the charm and flavor of one's personality, irrespective of his or her station in life, is what counts. In the third place, people may make blissful substitutions in the rosters of their associations, adding those they genuinely enjoy and admire.

Worldly status claims must be checked at the door in order that all within may be equals. The surrender of outward status, or leveling, that transforms those who own delivery trucks and those who drive them into equals, is rewarded by acceptance on more humane and less transitory grounds. Leveling is a joy and relief to those of higher and lower status in the mundane world. Those who, on the outside, command deference and attention by the sheer weight of their position find themselves in the third place enjoined, embraced, accepted, and enjoyed where conventional status counts for little. They are accepted just for themselves and on terms not subject to the vicissitudes of political or economic life.

Similarly, those not high on the totems of accomplishment or popularity are enjoined, accepted, embraced, and enjoyed despite their "failings" in their career or the marketplace. There is more to the individual than his or her status indicates, and to have recognition of that fact shared by persons beyond the small circle of the family is indeed a joy and relief. It is the best of all anodynes for soothing the irritation of material deprivation. Even poverty loses much of its sting when communities can offer the settings and occasions where the disadvantaged can be accepted as equals. Pure sociability confirms the more and the less successful and is surely a comfort to both. Unlike the status-guarding of the family and the czarist mentality of those who control corporations, the third place recognizes and implements the value of "downward" association in an uplifting manner.

Worldly status is not the only aspect of the individual that must not intrude into third place association. Personal problems and moodiness must be set aside as well. Just as others in such settings claim immunity from the personal worries and fears of individuals, so may they, for the time being at least, relegate them to a blessed state of irrelevance. The temper and tenor of the third place is upbeat; it is cheerful. The purpose is to enjoy the company of one's fellow human beings and to delight in the novelty of their character, not to wallow in pity over misfortunes.

Leveling also means welcoming people of different ages. Elderly people shouldn’t feel excluded, and youth should be welcome. Among the noblest of third place functions is that of bringing youth and adults together in relaxed enjoyment. The rampant hostility and misunderstanding between the generations, adult estrangement from and fear of youth, the increasing violence among youth-these and youth-related problems all have a common genesis and it is the increasing segregation of youth from adults. Where third places exist within residential neighborhoods, and are claimed by all, they remain among the very few places where the generations still enjoy one another’s company.

The transformations in passing from the world of mundane care to the magic of the third place is often visibly manifest in the individual. Within the space of a few hours, individuals may drag themselves into their homes-frowning, fatigued, hunched over-only to stride into their favorite club or tavern a few hours later with a broad grin and an erect posture.

Further, a place that is a leveler also permits the individual to know and be known. The great bulk of human association finds individuals related to one another for some objective purpose. It casts them, as sociologists say, in roles, and though the roles we play provide us with our more sustaining matrices of human association, these tend to submerge personality and the inherent joys of being together. This unique occasion provides the most democratic experience people can have and allows them to be more fully themselves.

I’m not sure that term is universal enough, but his point certainly is spot on. I was pleased to see it used in a mystery novel published in 1933, The Fear Sign by Margery Allingham, in reference to a game played by a publican and an aristocratic visitor:

Eager-Wright and Guff joined the dart players in the bar, while Mr. Campion engaged Mr. Bull, the landlord, at shove-ha'penny on taproom table, polished to glass by long years of eager play. The landlord was a past master with the five coins, and at sixpence a game was quite content to beat the harmlesslooking young man from London until closing time. Shove-ha'penny is a great leveller, and as the evening wore on, Mr. Bull and Mr. Campion reached a state of amity which might have been achieved only by years of different fostering.

Here’s my shorter explanation of the leveling we find in a third place:

The term leveller comes from the name of a radical left-wing party in England in the seventeenth century. It came to be applied much more broadly, referring to anything "which reduces men to an equality." For example, the newly established coffeehouses of that period were commonly referred to as levellers.

We might instead call such a place inclusive, in that it has no special requirements or membership fees. But the idea goes beyond inclusion: in a leveling third place, the common measures of distinction and hierarchy are replaced by other qualifications.

Leveling makes those who own a trucking line and those who drive a truck into equals. Rich or poor, successful or not so much, the pure sociability of a third place ensures that everyone is embraced, accepted, and appreciated for the charm and flavor of their personality. The inherent joy in being together is a truly democratic experience and allows us to know and be known, to feel seen.

Such a place doesn’t require tie and jacket or have exclusive seating, and the food and drink is moderately priced. But leveling doesn’t depend on rules. It’s a matter of atmosphere, of vibe. That’s hard to pin down, but decor can signal leveling by offering a mix of formal and informal, traditional and offbeat, a signal of welcome to anyone likely to turn up.

The Wainwright Inn in Great Barrington, shown below, is flying a Canadian flag at the moment. I was reminded of its colonial past: “Our house was originally built by Captain Peter Ingersoll in 1766 on the site of an older house built in 1720s by his father Moses Ingersoll, and was known as the Troy Tavern and Inn. The colonists undoubtedly met right in our living room, planning their participation in the siege of the British troops in Boston. During the American revolution, our house served as a fort and colonial armory.”

The foreword is by Martin Marty, whose death I learned of from a Russell Moore newsletter about the US turn against Ukraine. “In his analysis of the American religion of the first half of the 20th century, historian Martin E. Marty (who died last week) noted the anguish of Unitarian minister John Haynes Holmes in preaching a sermon in 1940 titled “Why We Liberals Went Wrong on the Russian Revolution.” Holmes, who was widely known in his day, was a ‘man of the left’ and had defended for years the Soviet Union and its promise of a just society.” I visited the Martys several times in Chicago, and when Marty Marty came to our area to speak at Hotchkiss School, I took Bill McNeill along to hear his old friend. Marty was a delightful conversationalist and a true gentleman, casual about his great reputation and regular invitations to the Renaissance Weekend. He startled me a few days before the 2008 election, standing at the window of the apartment they’d moved to, downsizing into the city. We were on the 88th floor, looking down on the park where Obama had launched his presidential campaign. “If he doesn’t win on Tuesday,” said Marty, “at least it’ll be easy to jump.” I wrote a little more about him in January: “A good word for the Good Book.”